AARP Hearing Center

As a city planner and walkability advocate, I find myself giving lectures most often at city planning conferences. No surprise there. But where do I find myself giving lectures the second most often? At conferences on aging.

Many older Americans really care about walkability. Too many others, however, assume that a good retirement or empty nest home requires ensconcing themselves in an age-restricted residential-only community a short drive from the mall. Here's why walkable communities are the best communities for older adults.

The "age-restricted community" is an anomaly of the second half of the 20th century. So is the residential-only community. None of these existed in significant number prior to 1950, when mass car-dependent suburbanization began to sort the American landscape into isolated areas of single use: housing subdivisions, shopping centers, and office parks, all stitched together — and also separated — by unwalkable arterial highways and collector roads.

Single-use also became single-demographic, as lifestyle-based marketing and increasingly narrow price ranges ruthlessly sorted the population by age and income into largely homogeneous clusters.

In this environment, which most of us now take for granted, the ultimate achievement may be the golf-course subdivision, where one can retire in peace, overlooking something resembling nature, with ample opportunity for recreation and automotive access to shopping and entertainment.

But most people who live in golf-course communities don’t golf, and only a small percentage golf regularly. More walk, but it’s difficult to get people to consistently walk for exercise. They start, and then they stop, discouraged that the walk serves no real purpose, ending right where it began.

This reality is well covered by Dan Buettner in his popular book The Blue Zones: Lessons for Living Longer from the People Who’ve Lived the Longest. (The subtitle of an updated edition has been rephrased to read as "9 Lessons for Living ...") After a tour of the world’s longevity hot spots, Buettner takes us through the “Power Nine: The lessons from the Blue Zones, a cross cultural distillation of the world’s best practices in health and longevity.” Lesson One: “Move Naturally.” He explains:

“Be active without having to think about it…. Longevity all-stars don’t run marathons or compete in triathlons; they don’t transform themselves into weekend warriors on Saturday morning. Instead, they engage in regular, low-intensity physical activity, often as a part of a daily work routine.”

Buettner quotes the late Robert Kane, M.D., then the director of the Center on Aging and the Minnesota Geriatric Education Center at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, who said:

“Rather than exercising for the sake of exercising, try to make changes to your lifestyle. Ride a bicycle instead of driving. Walk to the store instead of driving … Build that into your lifestyle.”

These admonitions are all well and good, but what if there is no store to walk to, no lifestyle available in which walking plays a useful role? In that case, walking can only be recreational, and therefore expendable. The Blue Zones can be found all around the globe, but they all share certain similar characteristics. One of these, and perhaps the most important, is that people don’t need cars to get around.

And this gets us to the second problem with the golf course subdivision, or, for that matter, any residential-only community: What happens when you become too old to drive?

As soon as someone loses his or her driver’s license — or, for many, their driving spouse of partner — the location of their suburban golf course home can become a trap. Unless the person can afford a very large Uber allowance, or is willing to burden a relative, he or she has no choice but to re-retire into a specialized home for the elderly. The residential retirement community is too often just a way station for the assisted-care facility.

Acknowledging the conveniences that walkable urbanism offers the elderly, sociologists as early as the 1980s identified what they call a N.O.R.C. — a Naturally Occurring Retirement Community.

Amateur observers have another term for it: “a walkable neighborhood full of old people.” Winter Park, Florida, is one such community, as is the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Many older American cities have their N.O.R.C.s, where a disproportionate number of elderly have moved due to the benefits of retiring in a walkable environment.

While many walkable places have become unaffordable due to their desirability, many others have not. Almost every midsize American city developed before 1950 has a downtown core that, a generation ago, lost a big chunk of its population. One by one, these are being re-inhabited, first by young people who don’t mind the grit, and eventually by older people who find it much improved by those who came before. Most cities sit on this curve; the trick is finding the right one.

Older Americans seeking to relocate face an important choice when it comes to their next home: a suburban residential community or a walkable urban neighborhood. Which one they chose will have a large impact on whether their daily lives are more sedentary and isolated, or more active, social, and fulfilling.

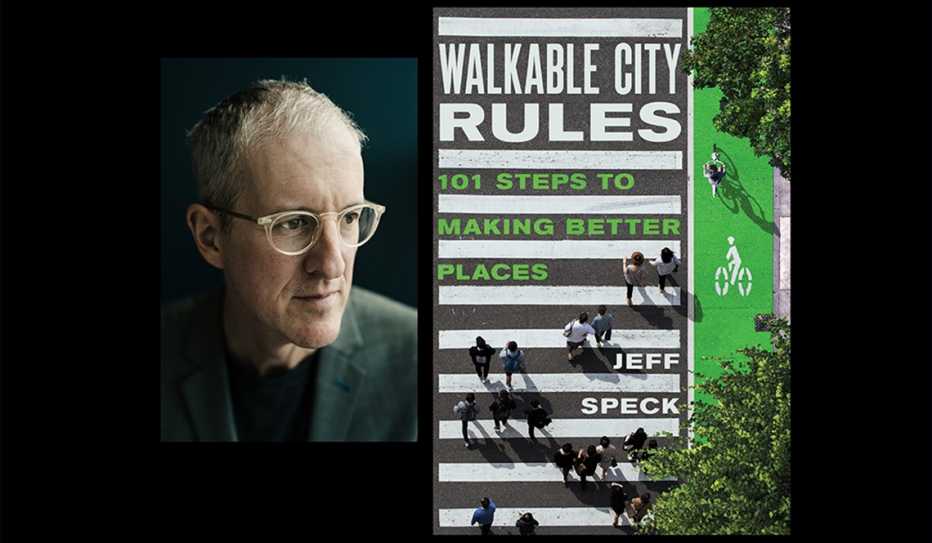

Jeff Speck is a city planner and urban designer who, through writing, lectures, and built work, advocates internationally for more walkable cities. He was a featured speaker at the 2017 AARP Livable Communities National Conference and is the author of "Walkable City Rules: 101 Steps to Making Better Places," published by Island Press.

Article published October 2018