AARP Hearing Center

Zoning codes and street standards are the very DNA of what makes — or breaks — a place, dictating where and how much parking is created, the width and location of sidewalks, and the placement of buildings.

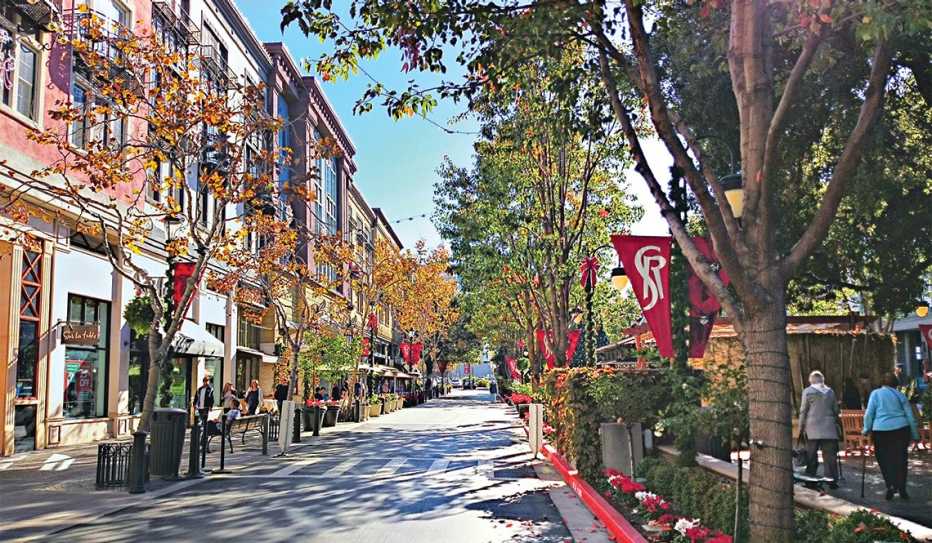

When designed appropriately, good codes can provide housing and mobility options, support economic development and jobs, and encourage the creation of commercial districts and neighborhoods that attract talent and equitably serve residents of all ages, races, physical abilities, incomes and family structures.

Watch a Lesson Video

As part of the AARP Livable Lessons video series, Lynn Richards, the former president and CEO of the Congress for the New Urbanism, explains how simple changes in zoning, codes and land development regulations can lead to better neighborhoods

Learn more: Livable Lesson: Incremental Code Reform

But the zoning codes adopted during the second half of the 20th century make it difficult or even illegal to create Main Streets and downtowns that feature storefronts with apartments above them.

Many people would like the option of having a small café or market within walking distance of their home.

Many would like to walk to work or downsize into a smaller home in the same community where they already live.

Yet current rules and zoning codes often prevent businesses from locating in or near residential areas, and they often prevent a mix of housing types (such as multifamily homes in neighborhoods with single-family houses).

In too many places, the local zoning code no longer serves the needs, vision or goals of the community. Solutions exist, but change is needed. Change often can't happen until there's widespread community support. The following steps and strategies can help:

1. Identify needs and how reform can help

Successful code reform has well-defined goals that cannot be achieved under the current code. As a starting point, advocates can cite examples of what isn’t working, or what is no longer allowed but could work well.

- Reverse past wrongs: Conventional zoning has been used as a tool for social and racial segregation. Reform efforts can work to reverse past wrongs and start eliminating inequities by increasing support for local business ownership, housing that’s affordable and protections against displacement.

2. Linking reforms to community interests and concerns

Who are the decision-makers and what are their interests? Are their goals consistent with the concerns of the general public? For example, the community’s elected officials and local leaders might be concerned about:

- Increasing opportunity: Code reform can allow for more flexible land use, which can contribute to larger community goals, such as rebuilding or strengthening the local economy, increasing housing choices, fostering attractive public spaces, improving safety, and creating opportunities for disadvantaged or underrepresented residents.

- Focusing on redevelopment zones and areas: Code revisions — such as improved design practices and simplified development regulations — can support community-desired changes for target investment in areas of need.

- The “plans that sit on the shelf” syndrome: At some point in its past, the community might have invested time and money in plans that were never implemented. Aligning code reform with a community’s master planning increases the likelihood of plans becoming a reality and allows the community to adjust to new challenges or opportunities

3. Predicting and addressing potential pain points

The language used to explain code changes should be as transparent and easily understood as possible. But even with misinterpretations off the table as a problem, common challenges include:

- Costs and capacity: Concerns about price and staffing are why it’s important for decision-makers to understand that incremental reform can be incorporated in less time, and with lower risk and cost, than a full overhaul of a zoning code.

- Legal questions: Since code reform efforts are typically vetted by a community’s attorney or land use expert before implementation, legal concerns shouldn’t prevent a community or its leadership from brainstorming about and considering new approaches.

- A lack of public support: The code reform approach outlined in this handbook reduces complexities and enables zoning codes to be tailored to local goals. Among the benefits of incremental code reform is that the process is easy for the public to understand — and support!

Enabling Better Places

This article is adapted from Enabling Better Places: A Handbook for Improved Neighborhoods, a free publication for local leaders and community advocates about incremental code reform.

Page published January 2021, updated June 2021