Return to Heart Mountain

Japanese-Americans interned during World War II tell their stories

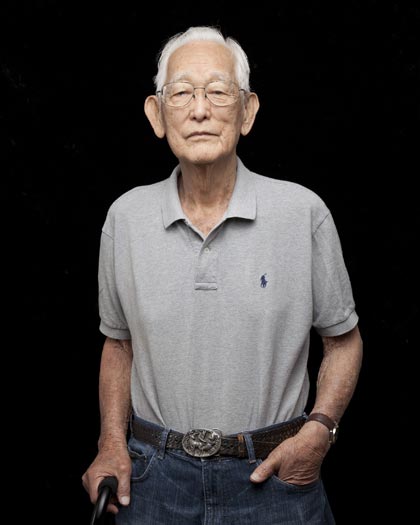

George Mouri, 89

George Mouri passed away two days after the reunion at Heart Mountain. His son Roger answered these questions on his behalf.

How old was your father when he arrived at the camp?

My father arrived at camp at the age of 19 with his parents and siblings.

How long was he there?

He was there about 13 months.

What was his strongest memory from the camp?

My father would do anything to get out of camp. He volunteered to work on the local beet farms. It was very hard work and very, very cold.

What did he do after he was released from the camp?

My father moved east for a civilian job, was investigated by the FBI to validate he was a loyal and trustworthy citizen and than drafted into the Army. He was assigned to the Military Intelligence Service to be an interpreter. After the war, he was assigned to Japan as an interpreter and became a paratrooper in the 11th Airborne Division. While on furlough, he married my mom.

How did he feel about Heart Mountain and that time in his life?

Some of my aunts and uncles were left with bitter memories, especially those who spent their youth in camp. My dad never expressed such bitterness. He moved forward in his life to provide each of his sons and daughter opportunities that we enjoy today. I am thankful he left us with so many memories.

Kazuko Kinoshita Copeland, 86

How old were you when you arrived?

I was 16 years old and came with my father, mother and 3 brothers.

How long were you there?

We were there about a year.

What is your strongest memory from the camp?

My strongest memory from camp was the weather. I was a girl from Los Angeles, and the dry wind in the summer and the cold wind in the winter was so different and harsh compared to California weather.

What did you do after you were released from the camp?

I went to Denver, Colorado, and lived with a Japanese family. In order to leave camp, I had to have a sponsor so I wouldn't become a ward of the state. We didn't know the family who took me in, but they were friends of some of our family friends. I stayed there with 2 other young Japanese-American women who left camp about the same time as I did. I stayed with the family in Denver for about 9 months and worked as a clerk in a drugstore. They were very nice to us. After 9 months I left Denver for Chicago, where my older brother was living and working. In Chicago the Quakers helped me and other Japanese-Americans find work and places to live. I ended up with a job in a printing company helping the printer and living in an apartment with another young woman.

How do you feel about Heart Mountain and that time in your life?

I have never been bitter over what happened. At the time, and to this day. I believe it was wrong for the U.S. government to take away our civil rights. Going to camp changed my life, and my life certainly turned out differently because of camp. I didn't get the education that my family and I had planned for me. I also learned that things can change quickly and that we have to make the best of life's situations.

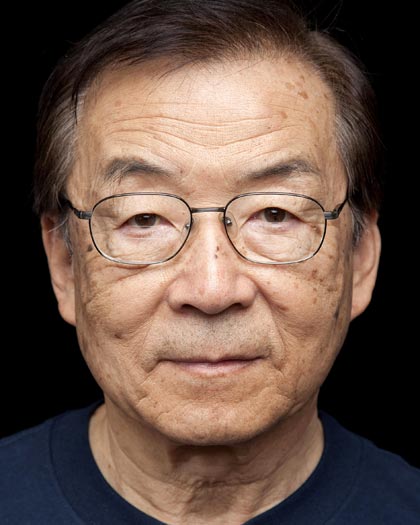

Kiyoshi Samuel Mihara, 78

How old were you when you arrived at the camp?

I was 9 years old upon arrival. I came with my parents and brother.

How long were you there?

I stayed there 3 years.

What is your strongest memory from the camp?

The most hurtful were the rejections from the local people, like the "No Japs" signs all over stores. Local undertakers would not take Grandfather's remains.

What did you do after you were released from the camp?

Upon departure, we transitioned to Salt Lake City, then eventually made our home in San Francisco. I married and now have 2 daughters and 2 grandchildren. I have a graduate degree in engineering and retired as an executive at the Boeing Company.

How do you feel about Heart Mountain and that time in your life?

Many people believe it was wrong to subject so many U.S. citizens to injustice. A few believe it was justified in time of war. Those of us who were interned suffered physically and emotionally. But I am gratified that I can pass on the story to others with the message that it should never happen again to anyone.

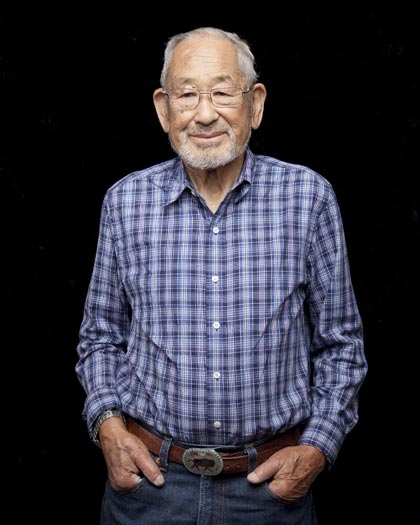

Jimi Yamaichi, 89

How old were you when you arrived at the camp?

I was 19 years old, and I came with my parents and nine siblings. My second brother was already in the Army, having been drafted before December 7, 1941.

How long were you there?

I was at Heart Mountain for a year.

What is your strongest memory from the camp?

My strongest memory of Heart Mountain was the bitter cold, especially coming from California and not being prepared for this type of weather.

What did you do after you were released from the camp?

Upon being released from camp, not from Heart Mountain but from Tule Lake, I returned to San Jose. I obtained my California contractor's license, made a career in construction, got married (now for 62 years), had 4 children (2 girls and 2 boys) who are all married and now am a grandfather to 4 granddaughters.

How do you feel about Heart Mountain and that time in your life?

When I arrived in Heart Mountain in 1942, I was a young kid, having graduated from high school in June 1941. Because I was in construction, I was assigned to supervise 15 much older men to repair the main canal where the water ran into the Heart Mountain basin. The confidence gained from this experience made me realize that I could be an effective and productive leader.

Kathy Saito Yuille, 68

How old were you when you arrived at the camp?

I was born in the camp.

How long were you there?

I was there for 2 years.

What is your strongest memory from the camp?

I was too young to have memories.

What did you do after you were released from the camp?

My parents returned to San Francisco.

How do you feel about Heart Mountain and that time in your life?

My parents hardly ever spoke of their experience at Heart Mountain as I was growing up. They chose to look forward instead of looking back. Perhaps it was too painful and there was no point in talking about it if it didn't help them improve their situation after the war. It was actually my daughter when she was in middle school who started prodding me about the incarceration experience as it related to my parents and children. She wanted to learn more.

Franklin Mitsuo Nishiura, 69

How old were you when you arrived at the camp?

I was 2 months old when we were taken to Santa Anita racetrack and either 4 or 5 months when we arrived at Heart Mountain.

How long were you there?

We left the camp in 1945, so I was 3 years old. My entire family in the U.S. was at Heart Mountain, 18 people plus 3 who were born there.

What is your strongest memory from the camp?

I have no direct recollections of the camp. My only knowledge is from what I heard from others and from the few photos we have of that time. There was almost no conversation of that time, as was the case in most families.

What did you do after you were released from the camp?

When we left the camp we returned to Mountain View, California, where we stayed at a hostel for returning families who didn't have any place to go. My father, Shingo Nishiura, was the hostel manager. I am a retired structural engineer enjoying babysitting my grandkids and acting as chauffeur while their parents work.

How do you feel about Heart Mountain and that time in your life?

[At the reunion] I heard more stories and recollections than I had heard in the previous 69 years of my life. Since everyone except one who was born there was older, I learned much about the camp and was privileged to hear some of the emotions of my fellow travelers. Our family lost almost everything when we were forced to sell what we could in a week or so before we were forcibly removed from our homes and lives. After hearing stories from others, I now have a better understanding of what the older people went through and what angst the uncertainties of that time caused. I also understand how the parents of the children of the camps tried as best they could to shield their children from the fear they all felt. In retrospect, it was probably the most insightful experience of my life.

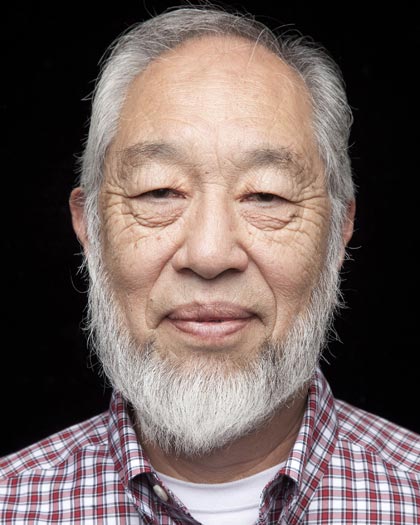

Bacon Sakatani, 82

How old were you when you arrived at the camp?

I turned 13 on the train ride to Heart Mountain in August 1942. I was with my parents, 2 older brothers, an older sister and a younger sister.

How long were you there?

I was there almost 3 years.

What is your strongest memory from the camp?

We had one room for 7 of us.

What did you do after you were released from the camp?

We went to an Idaho potato farm to pick potatoes. When winter came and there were no more jobs, we returned to California to start all over again, with hardly anything. This was the toughest part of our total experience. But we made it. When I got out of school, I served in the Korean War, got married and had three children, worked at various jobs and retired.

How do you feel about Heart Mountain and that time in your life?

For my parents, they lost everything, all of their life’s work. As a teenager I didn't know anything of what was going on, just tagged along to camp and spent three years there running around with kids my age with what was available to us. For us kids, we had football and Boy Scouts to keep us out of trouble and occupied. But to learn many years later that it was all due to "race prejudice, war hysteria and a lack of political leadership," as stated by the commission established by Congress, and then to receive an apology by President Bush and a check was really something. Heart Mountain should never have happened.

Patricia Yamakawa Yamamoto, 74

How old were you when you arrived at the camp?

I was 4, almost 5, on my arrival at Heart Mountain on August 21 or 22, 1942. I came with my parents, David and Shizu Yamakawa, older brother, David, Jr,. age 6, and paternal grandmother, Lucy Aiko Yamakawa.

How long were you there?

We were there over 3 years, departing October 16, 1945.

What is your strongest memory from the camp?

The anti-Jap signs in Cody.

What did you do after you were released from the camp?

Our family returned to San Francisco and lived for the first 2 years in a dormitory outside the naval shipyard with other Japanese-American families because we had no other housing. We moved in 1947 into then-segregated public housing, Hunter's Point Housing Project, and I wondered why we had been put in "camp" for being of Japanese ancestry and now we were in the "white" section of the housing project. It didn't quite make sense to a 10-year-old.

I graduated from UC Berkeley in 1959. I had a short career as a first-grade teacher and got married. We have 3 children and 1 grandchild. I continue to be a substitute teacher in classes for the developmentally disabled and persons with autism.

How do you feel about Heart Mountain and that time in your life?

It was a grave injustice to all who were interned, imprisoned just because we were Japanese-Americans. I feel very strongly that we, as a society and as individuals, must keep this story alive, not because of self-pity, but because I do not want such injustice to be repeated on any other group of people. We, as a society, forget the past easily and repeat the same mistakes. I must always be vigilant and speak out when there is any outcry against groups of people, such as against persons of Middle East origins and Muslims after 9/11.