Take Control of Your Financial Future With These 4 New Rules

Fresh ways to think about wealth and funding your retirement

En español | When it comes to money and retirement, we have the best of intentions. What many of us lack, however, is lots of money-management experience or expertise. So we grab hold of ideas about how to shore up our retirement security — ideas we have read about, have heard about or maybe had ingrained in us in our youth. And then we implement those ideas as best we can.

But what if those money “truths” are wrong? Based on my two decades of experience as a financial planner, I would say that many widely held, responsible-sounding bits of money wisdom are unwise and ought to be turned on their heads. After all my work with retirees and near-retirees, I've got a pretty clear picture of four new ideas that need to replace the old saws, if you are to retire safely and smartly.

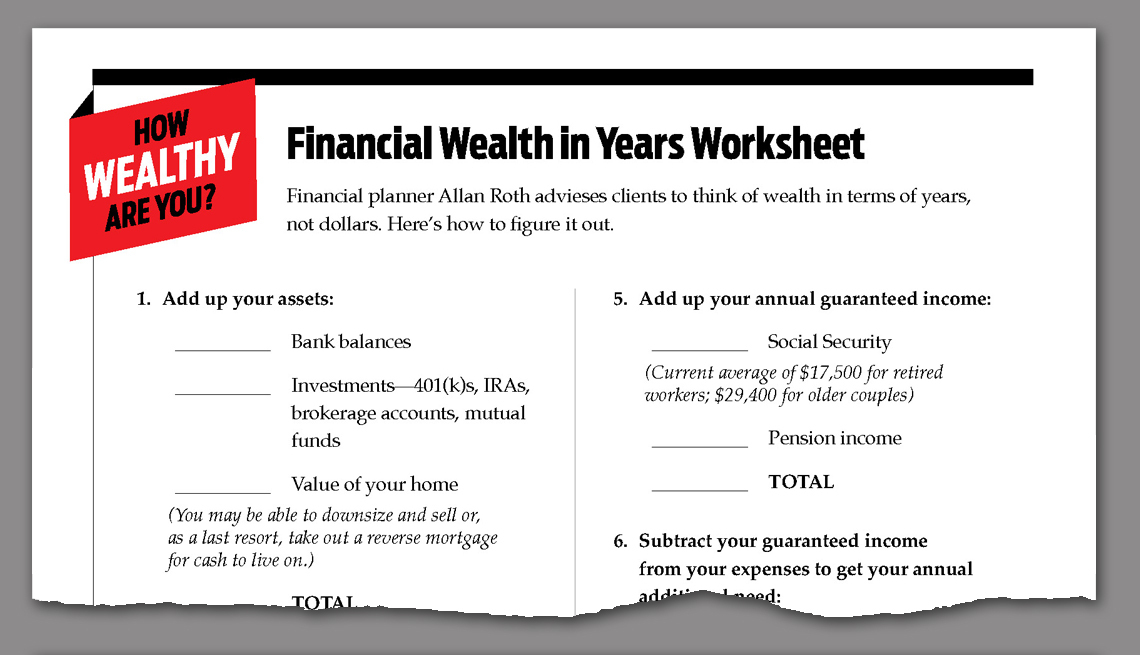

New Rule No. 1: Wealth is not a dollar amount

Most of the time, when we think about whether we're ready to retire, we fixate on a number — the amount of money we believe we need saved up by retirement time. It could be $50,000, $500,000 or even more. People think they need a certain number of dollars in hand to live comfortably. I hear this a lot.

But for anyone hoping to finance at least part of their retirement with savings, this is the wrong approach.

Here's why. Over the years, when I ask people what money means to them, they don't talk about cars or boats or second homes. Instead, they use words like “freedom,” “security” and “choices.” They talk about a future in which they can enjoy financial independence. The important number for them isn't the size of their pile of cash. It's the years of freedom that pile represents.

Judged by that, the wealthy person may not be who you think. Someone who is worth $1 million and who lives a lifestyle costing $200,000 a year has only five years of freedom and security.

"Looking at wealth in terms of time rather than dollars can be a powerful tool for financial security."

On the other hand, a person worth $200,000 who lives on $10,000 a year, plus Social Security, has 20 years of financial independence. (That's based on the simple, conservative assumption that your nest egg is invested and keeps pace with inflation and taxes.) The second person, I believe, is the wealthier one.

So start thinking about wealth as a ratio: the money you have compared with the money you need to live the life you desire for as long as you choose. And use the accompanying worksheet to see how wealthy you really are. Looking at wealth in terms of time rather than dollars can be a powerful tool for financial security.

New Rule No. 2: A penny saved isn't a penny earned — It's more

So it's my contention that wealth, once you have met the basic needs that will make you happy, is all about time, not money. In that case, you have two ways to become wealthier: Make more money or spend the money you have more wisely. Guess which choice is easier.

Let's say you have a net worth of $200,000 and currently spend $20,000 annually above Social Security payments. You have 10 years of financial wealth. Cutting $10,000 in annual expenditures (or a little over $800 a month) by eliminating some expenses and getting better deals on others will double your financial wealth to 20 years.

By contrast, earning more money in order to maintain that $20,000-a-year lifestyle is a lot harder to sustain. Say instead of cutting your spending by $10,000 a year, you find a way to make an extra $10,000 each year. Now, you won't get all that money, because some of it will go to taxes. But let's say you are willing to work 10 more years to sustain your current spending levels. Doing that might bring in a total of $80,000 after taxes, increasing your net worth to $280,000. Sticking to your $20,000 annual spending rate, you end up with about 14 years of wealth.

Take notice: Spend $10,000 less per year, and you immediately gain 10 years of wealth. Spend a decade making $10,000 more a year, gain about four. Living smarter and more frugally has a much bigger payback than taking on a side hustle. Cutting back on spending now and committing to lower costs in the future can boost your wealth and move up your financial independence by several years.

But won't spending less make you less happy? Probably not. We quickly get used to living on less, just as we quickly get used to living on more, says Dan Ariely, professor of psychology and behavioral economics at Duke University. Research indicates that we get more happiness from experiences than buying stuff. The new luxury car may bring short-term happiness, but experiences, like taking the children and grandchildren on a modest vacation or even just taking the grandkids out for a treat, provide memories (and happiness) that can last a lifetime, says Jonathan Clements, author of From Here to Financial Happiness.

So how do you know what you can cut out to bring more wealth? Start now and look at where the money goes. The biggest expense, amounting to one-third of the budget of the average household headed by someone 65 or older, is housing, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports. Transportation, health care and food are next in line.

Limiting car expenses is the easiest and least painful way to cut costs; buy a modest car and keep it for a decade or longer. Downsizing to a smaller home with lower taxes and maintenance costs, or to a rental, is a bit harder. (Forget about moving to a less expensive city where you don't know anyone. A support group of friends and family is essential for happiness, Clements says.

Cut something out for a month or two and see what that does to your happiness, Ariely suggests. Eating out once a week instead of three times, Clements says, may actually make you happier; the lower frequency will help you enjoy it more, and anticipation of the meal itself brings happiness. Try keeping a daily journal of what has made you happiest. It's far more likely to be interactions with people that cost you little or nothing than a night out at a pricey restaurant or a long walk through your McMansion.

New Rule No. 3: He who hesitates cashes in

People regularly take Social Security as soon as possible rather than spend any of their retirement kitty. I get why. After a lifetime of saving money, it's hard to reverse course.

But taking benefits ASAP to guard your nest egg is typically a mistake. A better choice, if you're able, is to spend savings today so you can delay taking Social Security. The reason — and I can't state this strongly enough — is that you'll be buying what I think is the best annuity on the planet: one that is guaranteed by the government, keeps pace with inflation and has a survivor benefit. And each month you wait to take Social Security, it gets better. For instance, delaying payments from age 66 to 70 can raise your monthly benefit 32 percent, even before cost-of-living increases kick in.

Consider the case of Sue, 66, a married woman who is the primary earner in her home. If Sue delays taking Social Security until she is 70, I figure she will have to pull about $36,000 annually (plus inflation) from her savings over the next four years to replace the benefits she would have gotten if she claimed. In return, however, when she does claim at 70, she'll get a monthly benefit that's $1,040 higher than it would be had she claimed at 66. To buy that $1,040 extra per month as an annuity on the private market — one that keeps pace with inflation and has a survivor benefit — would cost nearly $252,000.

To recap: In return for using up $150,000 in retirement savings, Sue would get a government annuity that, had she bought it elsewhere, would cost her $252,000. She's getting a discount of more than 40 percent.

So don't think of spending your money now as reducing your wealth. Think of it as increasing your wealth by buying that bargain annuity, says Steve Vernon, author of Retirement Game-Changers: Strategies for a Healthy, Financially Secure, and Fulfilling Long Life.

Admittedly, decisions about when to take Social Security may also depend on other factors, including age and health. Mike Piper, author of Social Security Made Simple, offers these rules of thumb:

If you are single, the better your health is, the more sense it makes to wait.

If you're the higher earner in a married couple, you should probably wait until 70 unless both you and your spouse are in very poor health.

If you are the lower earner in a married couple, filing early is fine, especially if either of you is in poor health.

But run the numbers first. AARP has a Social Security calculator that helps with decision-making for individuals. And, OpenSocialSecurity.com, Piper's free online tool, is especially useful for couples.

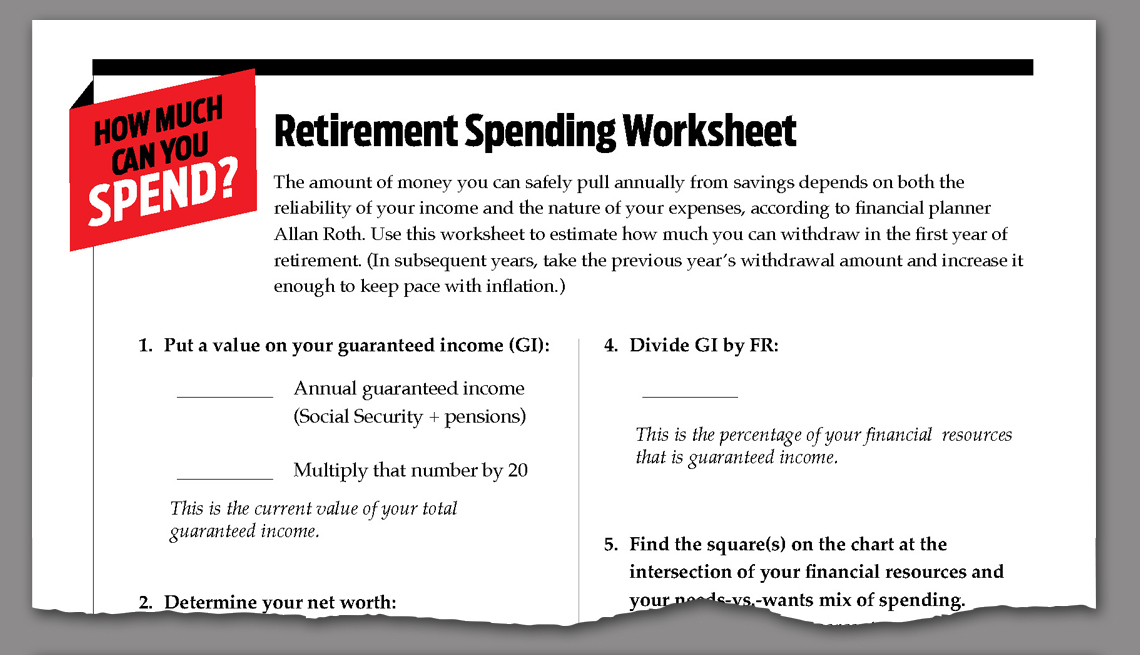

New Rule No 4: All Rules Should Be Turned Upside Down

One of the best-known approaches to managing money in retirement is known as the “4 percent rule.” Based on the assumption that you have your savings invested in a mix of stocks and bonds, the rule dictates that you can withdraw 4 percent of your portfolio to live on in the first year of retirement, then increase the annual withdrawal each subsequent year just enough to keep up with inflation. That rule has tended to be a good guideline for minimizing the chances that you'll run out of money over a 30-year retirement, while also preventing unnecessary self-denial.

But consider the hypothetical case of two couples: the Johnsons and the Petersons. They're all 65 years old, they're all collecting Social Security, and each couple has set aside some retirement savings. There are two big differences between the couples, however. One, most of the Johnsons’ retirement income is from guaranteed sources, like Social Security and pensions, while most of the Petersons’ comes from savings — the money they pull from their 401(k)s and IRAs.

“Rules are usually just wise guidelines to be bent and adjusted based on our situations."

Two, what the couples spend their money on is different. With their home and debts paid off, most of the Johnsons’ spending is discretionary; it's optional stuff that they can cut back on in lean times, like vacations and dinners out. On the other hand, most of the Petersons’ spending is nondiscretionary, like mortgage payments and utilities; it's what's referred to often as needs, not wants.

Given these differences, these couples shouldn't live by the same rule, argues David Blanchett, head of retirement research for the financial information company Morningstar. He proposes that your safe-spend rate — that is, your version of the 4 percent rule — should take into account how much of your income is guaranteed and how much of your spending is discretionary. The greater the amount of each, the more you can risk pulling from your savings each year. In this case, he might suggest that the Johnsons can afford to withdraw 5 percent of their retirement savings in year one, not 4 percent — in part because, if economic conditions turn sour and markets fall, they can easily cut back temporarily on their discretionary spending. But the Petersons — who have fewer places to cut back in hard times — should withdraw only 3 percent that first year.

See my point? In the world of money guidance, each of us is unique. “Rules” are usually just wise guidelines to be bent and adjusted based on our situations.

Even my advice for achieving financial freedom may not work for you. Maybe after you calculate your income and trim your spending, you decide that you're not yet financially free. That doesn't mean you should stay at your job if you hate it. The stress that comes from working at a job you hate may shorten your life expectancy — a lousy way to achieve financial independence.

So I often tell people to consider making less money but doing something they love. Say there is a nonprofit with a cause you are passionate about — an organization where you'd take home only half the income that you do now. Even though that might double the time it would take you to achieve financial independence, that job could bring you more happiness, less stress and a greater sense of purpose. You might even be inspired to work there longer than is necessary to achieve financial freedom.

You might also find it better than a cold-turkey retirement. It gives you time to adjust to your new life. You bring in some money and give yourself less time to spend it. I've found that people who fully retire early actually spend more than they did when they were working because they have more time to travel, eat out and do other things that cost money.

Allan Roth has been a financial planner for more than 20 years.

Free Planning Tool

AARP Money Map is a guide to manage unanticipated expenses