AARP Hearing Center

Retirement Planning

Sheltering the Silver Rainbow

LGBTQ+ retirement communities are rare. Some developers are stepping up to meet the need

By Daniel Vaillancourt, AARP

Published June 14, 2024 EN ESPAÑOL

Doug Hairgrove and Warren “Woody” Wood were together for 65 years. They met in college in 1959, worked side by side for more than three decades at a Southern California junior high school and got married in 2008 at their desert home in Palm Springs, California.

When it came time to downsize a few years ago, they initially moved to a condo. “It was nice, but it was the way many of the condos are built here — we had very little contact with others,” says Hairgrove, 84.

They longed for a place that offered social amenities like movie nights, crafts classes and communal dinners, but moving to a conventional retirement home “never crossed our mind.” They had heard stories of LGBTQ people being harassed and mistreated in traditional facilities, Hairgrove says. “We wanted to live with other gay folks.”

The couple found what they were looking for in November 2023, settling at Living Out Palm Springs, a newly opened apartment community for LGBTQ+ people and their allies ages 55 and up. Wood died May 27, at the age of 85. But he was able to live his last several months in a community of peers.

“We just knew this would be a safe place,” Hairgrove says.

Their concerns about finding that place are widely shared. In a June 2022 AARP survey of older LGBTQ+ adults, 41 percent said they were concerned about hiding their identity to avoid housing discrimination as they age. Fifty-eight percent of trans and nonbinary respondents felt they might need to conceal their identity to access housing.

Addressing such concerns was a driving force behind Living Out. The company that developed it, KOAR International, is headed by Loren Ostrow, a gay man, and his straight business partner, Paul Alanis.

“As LGBTQ people, we had to learn to navigate a world that wasn’t built for us,” Ostrow says in a history of the project on its website. “Living Out reverses that paradigm by building a world especially for us.”

Some advocates, academics and builders believe Ostrow’s paradigm shift may be poised to play out on a broader scale.

“I think because of culture shift and visibility, people are seeing that LGBTQ+ people are aging in need of culturally responsive, affirming housing,” says Sydney Kopp-Richardson, director of the National LGBTQ+ Elder Housing Initiative at SAGE, the nation’s oldest and largest organization serving older lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer people.

"Housing developers — both nonprofit and for-profit, affordable housing developers — are seeing this market and really capitalizing on it."

Escaping exclusion

SAGE estimates that by 2030, some 7 million LGBTQ+ Americans will be 50 or older. While they have witnessed the civil rights sea change of the past decade — marked by the Supreme Court’s watershed rulings enshrining marriage equality and prohibiting workplace discrimination based on gender identity or sexual orientation — their formative experiences were often shaped by exclusion and bias.

“Decades of discrimination have impacted LGBTQ+ elders,” Kopp-Richardson says. “Aging is not linear. It’s subjective depending on what you’ve experienced ... We see compounded isolation for many in our communities who don’t have children, or who are estranged from their family of origin.”

Nor are legal and social barriers entirely a thing of the past. There is no federal law prohibiting housing discrimination based on gender identity or sexual orientation, and fewer than half of states have such laws on the books, according to Human Rights Campaign, an antidiscrimination group.

For many LGBTQ+ older adults, memories of being stigmatized, rejected by family and friends, or keeping their sexuality secret to hold a job or serve in the military may render them less inclined to live openly or make waves.

Al Blencoe and Dean McIntosh — 85 and 91, respectively, and together for 55 years — encountered overt homophobia after moving into a mainstream independent living community near Palm Springs in 2021. “We would not walk down the hallway holding hands,” says McIntosh. Once their two-year lease was up, they moved to Living Out.

“Housing is a social determinant of health. You cannot live a healthy life if you don’t have a stable home environment,” says Jason Flatt, an associate professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas School of Public Health and a scholar of LGBTQ+ aging.

“You’re going to be afraid. You’re not going to build close relationships with anyone in that setting, because you’re going to be afraid of getting too close," he says. "And then there’s the likelihood that you’re also being exposed to homophobia, transphobia, other forms of discrimination. It just exacerbates the internalized fear you have about getting outed.”

Affordable housing most common

Developments such as Living Out offer older LGBTQ+ adults an upscale version of affinity housing — a community or facility where members of a marginalized group choose to live in proximity to each other.

A self-described “luxury” complex with mountain views and amenities that include a gym, swimming pool, pet park, putting green and a restaurant run by celebrity chefs Susan Feniger and Mary Sue Milliken, Living Out’s rents range from $4,999 to $8,299 a month (weekly housekeeping and all utilities included). That’s comparable to the cost of an assisted living facility but still far out of reach for many LGBTQ+ elders.

Historically, LGBTQ+ affinity housing has generally meant affordable housing, often tied to nonprofit organizations that offer community-based activities and social services such as health and wellness education, support groups, and food and transportation assistance.

The first such community in the country, the 104-unit Triangle Square Apartments, opened in Los Angeles in 2007. It is now owned by the Los Angeles LGBT Center, which also operates Ariadne Getty Senior Housing, an LGBTQ-friendly complex in Hollywood for people ages 62-plus with lower incomes.

Residents pay a share of the rent, based on their income compared to local standards, “but that rent is subsidized either through government sources and/or private fundraising,” says Center CEO Joe Hollendoner. “Fortunately, we’re in Los Angeles, where there is not only wealth but generosity.”

According to data from SAGE, there are currently 31 LGBTQ-friendly affordable housing complexes already in operation or in development across the country, spread across 14 states and the District of Columbia. One of the newest is The Pryde, New England’s first LGBTQ-friendly elder housing community, established in a circa-1902 former schoolhouse in Boston’s Hyde Park neighborhood.

“It’s an incredibly beautiful historic building, a beloved landmark in the heart of Hyde Park,” says Gretchen Van Ness, executive director of LGBTQ Senior Housing Inc., a nonprofit dedicated to creating affordable housing that is welcoming to LGBTQ+ older adults.

As mandated by Massachusetts’ fair housing laws, occupancy was awarded via a lottery governed by the city of Boston. The Pryde received more than 700 applications for 74 apartments, Van Ness says. The developers are aiming for move-ins to start in June, Pride month across most of the U.S.

“We’re already looking for our next project,” she adds.

Partnering on The Pryde is Pennrose, a real estate development and management firm with offices in eight major cities and more than 170 properties in 13 states. Affordable LGBTQ+ housing is a specialized focus for the company but a growing one, with three such projects under its belt — The Pryde, John C. Anderson Apartments in Philadelphia (opened in 2014) and John Arthur Flats in Cincinnati (2022) — and three more in the works.

“Years ago, in my naivete, a couple of us at Pennrose were theorizing that this was a thing of the past and wouldn’t be part of our future,” Timothy Henkel, the company’s president, says of its continued involvement in developing LGBTQ-friendly housing.

“But here we are, more than a decade later, knowing that the need persists, the need has maybe increased,” he says. “We [still] need to create some of these spaces that are clearly off-limits to discriminatory behavior.”

‘The first time they felt safe to live openly’

While affordable housing remains the dominant model, LGBTQ+ retirement communities have broadened into different shapes and sizes that echo developments in the mainstream active-adult market.

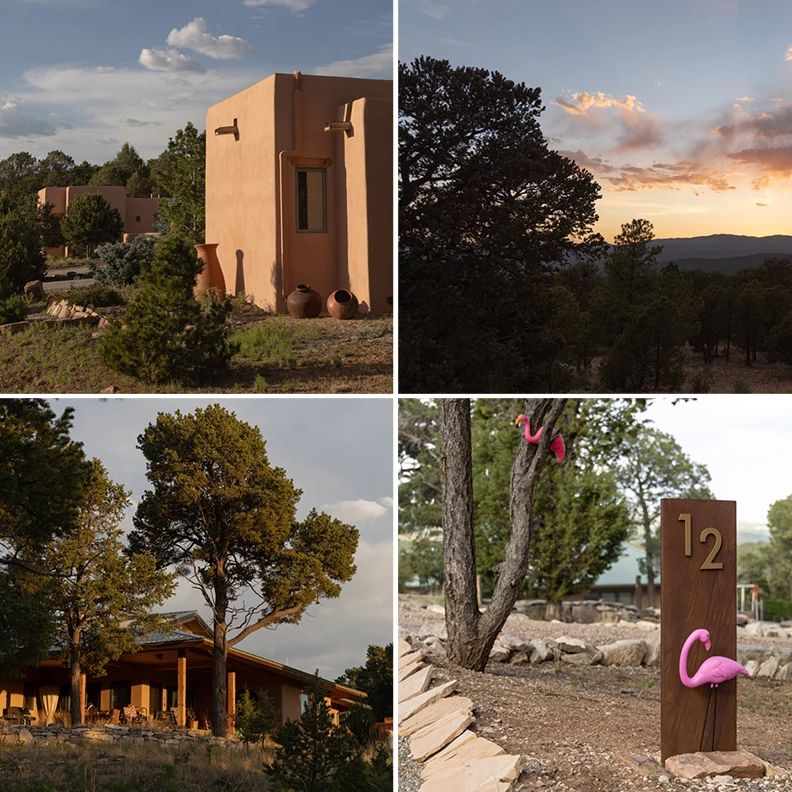

Birds of a Feather in Pecos, New Mexico, bills itself as “one of a very few gated LGBTQ-friendly communities in the country,” with homes spread across 140 acres and prices ranging from $60,000 to just over $200,000, as of May.

When it opened in 2004, “a lot of the people I sold lots to had been closeted their entire life,” says founder Bonnie McGowan, 74. “This was the first time they felt safe to live openly as who they really are.”

Village Hearth in Durham, North Carolina, launched in 2020 by spouses Margaret Roesch, 68, and Pat McAulay, 69, adapts the innovative cohousing model for LGBTQ+ elders and allies.

The community consists of 28 one- or two-bedroom cottages, clustered in seven groups of four, each with native gardens and private backyards. Sale prices range from $345,000 to $465,000, and there are monthly homeowners’ association dues of $385 to $521.

There’s also a common house with a craft room, guest room, communal kitchen and washer/dryer; a maintenance building with a shed and woodshop; a dog park; and 10 acres of wooded grounds with walking paths.

Residents see the common house as an extension of their own homes, gathering there weekly for communal meals, and share resources, says Nan Kelly, 70, who lives at Village Hearth with her wife of 20 years, Kate De Haven, 78. Both are retired social workers.

“If I need a shovel, I don't have to go out and buy a shovel. I go to the storage shed, sign it out, and come home," she says. Residents walk each other's dogs and provide rides to neighbors who don't have cars.

“The culture of collaboration and cooperation is the norm,” she adds. “If you’re not doing that, someone’s gonna let you know.”

If you build it, will they come?

Back in Palm Springs, Ostrow has designs on replicating the Living Out model in other markets with significant LGBTQ+ populations and says he is open to offering more moderately priced versions.

“I think it’s going to become clear to the investment community that this is a product of the future,” he says.

Sam Chandan, founding director of the C.H. Chen Institute for Global Real Estate Finance at the New York University Stern School of Business, is also bullish on LGBTQ-friendly retirement housing. He is spearheading a study of Living Out as a test case for tapping this growing market.

“Many lending institutions are able to model and estimate what construction costs will look like and what ultimately operating costs will look like, but absent a large number of LGBTQ+ senior housing projects, it’s more challenging to estimate what demand will look like,” he says. “What will the market bear in terms of rents? What will occupancy look like? What will the stabilization period look like from the time a project opens to when it reaches its steady state of occupancy? What will tenant retention look like?”

Chandan says he hopes his analysis will provide investors with the tools to move forward on LGBTQ-focused developments across the affordability spectrum and show that such projects are financially worth pursuing. Making the business case, he adds, serves a deep social need.

“The motivation for many of us is wanting to ensure members of our community are able to age with dignity, in a way that’s authentic, surrounded by people who care for and love them,” he says.

That’s what novelist Katherine V. Forrest, 85, found after she and her wife of 33 years, Jo Hercus, 70, moved into Living Out. Forrest, author of the award-winning mystery series featuring lesbian detective Kate Delafield, likens finding a late-life home in a community of peers to “a happily ever after answer in a novel.”

“This is a proof of concept that I think is incredibly valuable,” she says. “If people in our community with money really want to do something that changes lives, makes a difference, leaves a footprint, this is it.”

Daniel Vaillancourt is a freelance writer based in Palm Springs, California, where he lives with his husband. He is a regular contributor to The Envelope, the awards season supplement of the Los Angeles Times.

MAIN PHOTO: Standing: Loren Ostrow (left) and Paul Alanis (right), developers of Living Out in Palm Springs; Bonnie McGowan, founder of Birds of a Feather in Pecos, New Mexico. Seated (from left): Tom McCauley, Charles Carroll and Michael O’Rourke at John C. Anderson Apartments in Philadelphia; Pat McAulay and Margaret Roesch, founders of Village Hearth in Durham, North Carolina.

More From AARP

11 Housing Options for Those Who Can’t Age in Place

Older adults want to stay in their homes but can’t always

Telling Your Story: Preserving History with LGBTQ+ Older Adults

Storytelling can be a powerful experience for all involved

Stonewall Moments: Honoring Icons in LGBTQ+ Activism

Meet six activists AARP is recognizing for Pride MonthRecommended for You