AARP Hearing Center

When people think of age discrimination, they usually envision workers fired, denied promotions or never hired simply because of their age.

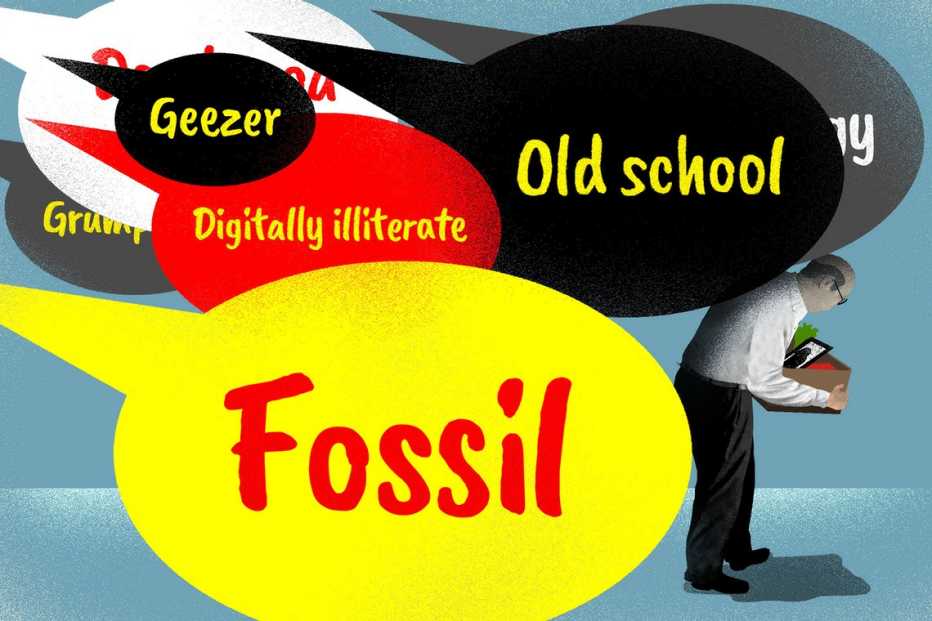

But what if it’s not your livelihood at stake, but more your professional identity and self-worth? What if you are bullied, made miserable or feel threatened by remarks or actions on the job that focus on your age?

Liz DiMarco Weinmann can tell you. She was in her 50s, working in Washington, D.C., for a public affairs company when, in a meeting with an important — and younger — client, she briefly forgot the name of a spokesperson. “This man started swearing and cursing at me and saying, ‘I am sick and tired of you not having your young staff here who really knows what’s going on,’ as if I were senile,” she recalls. “He took the papers that were in his hands and threw them at me from across the room.”

When Weinmann reported the episode to her manager, the boss compounded the outrage by telling her that if the company lost the account, it’d be because she couldn’t remember things. “It was totally despicable,” she recalls. “That experience was the closest I’ve ever come to thinking to myself that I would just roll up and never work again.”

Age harassment, whether it is deliberately or inadvertently hurtful language, is every bit as illegal as other forms of age discrimination. Yet verbal harassment isn’t taken as seriously. And it can be particularly difficult to get justice in the legal system if you are harassed.

“If you come home and say, ‘I’ve been accused of calling someone an ‘old fart,’ no one bats an eye,” says Michael Borrelli, an employment attorney with Borrelli & Associates in New York. “Older people are the forgotten group that no one cares about. As far as standing in society, they are totally discounted.”

Donna Ballman, an employment attorney in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, agrees. “Older people are getting targeted a lot” by hostile, inappropriate language, she notes.

The data supports that. The federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) said in a recent report that age-based harassment claims more than tripled between 1992 and 2017. A national survey of 3,900 workers by AARP Research in 2018 found that nearly 1 person in 4 had heard a boss or a colleague make a negative age-based remark about them.

Weinmann, now 67, returned to New York after the incident in Washington and got an advanced business degree. She now owns a consulting practice and advocates for older workers. That includes talking to MBA alumni at New York University about the age harassment they can expect to face as they get older. The language of ageism is “pervasive” in business, she says. “People think that when you get to a certain age, you’re not important.”

Special Report: Age Discrimination in America

Workplace Age Discrimination Still Flourishes in America

It's time to step up and stop the last acceptable bias

Age Bias That's Barred by Law Appears in Thousands of Job Listings

With the words they use, employers keep experienced workers from applying

Fighting Age Discrimination in the Courts

They fought against companies like Google and Ruby Tuesday, but justice was elusive and incomplete