AARP Hearing Center

The thought that “life is a journey, not a destination,” sparked the founding of AARP’s Institute of Lifetime Learning.

AARP’s founder, Dr. Ethel Percy Andrus, announced the Institute on May 24, 1963, while testifying before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Education and Labor in support of the Adult Education Act of 1963. Calling it a “great experiment,” she said the new service would be “an informal school offering courses to our members to meet their intellectual needs and to enhance their skills and talents.”

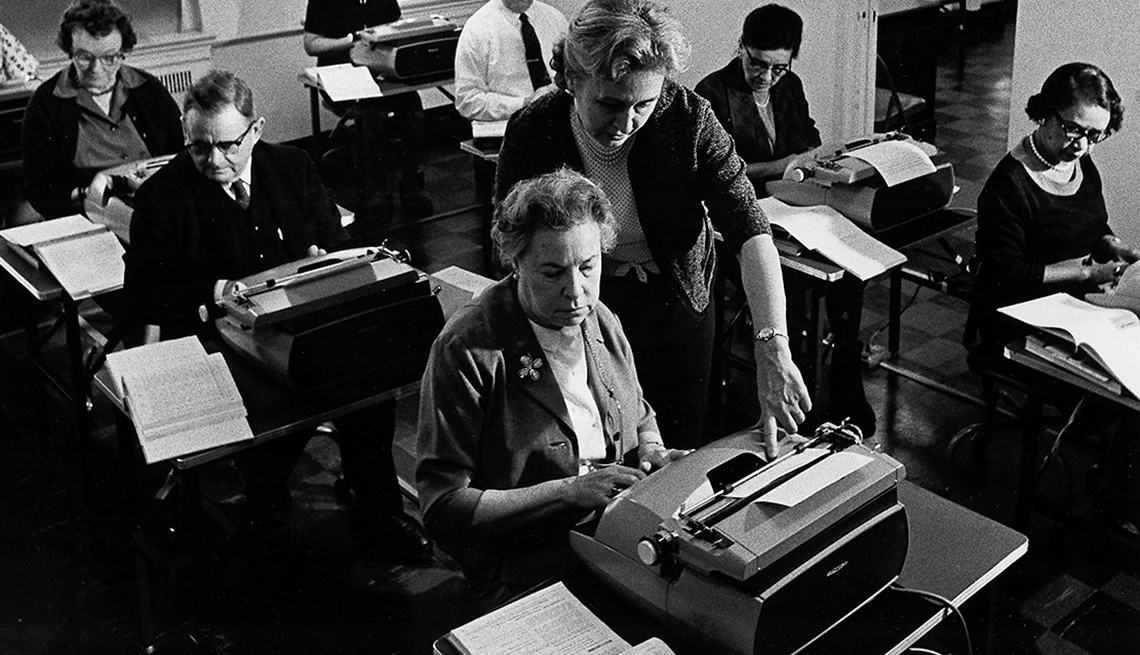

AARP’s Institute of Lifetime Learning opened its doors on Sept. 1, 1963, in a building adjoining AARP’s headquarters on Dupont Circle in Washington, D.C. It was set up as a demonstration project to document the interest of older persons in education and their desire to keep abreast of changes that affect all society. The idea was to create programs that could be duplicated wherever older people wanted to pursue their interests and develop new skills.

The Institute offered three types of activities:

- Public lectures that integrated presentations of facts and ideas with audience participation. Topics included art, mental health, politics, business, philosophy and religion.

- Special interest seminars, led by scholarly experts, which fostered a deeper understanding and appreciation of a subject area or set of ideas.

- Training in “practical skills and avocations” to help students “continue personal stimulation and extend useful service to the community.” These included music appreciation, photography and flower arranging.

Based on the success of the pilot, the Institute opened a second location in Long Beach, Calif., in 1965, and a third in St. Petersburg, Fla. To extend its reach beyond these classrooms, the Institute launched “Let’s Listen to Lifetime Learning,” which made recordings of actual classes available to radio stations for play across the nation.

The Institute played a major role in a national revolution in attitudes and opportunities regarding education and older Americans. Education would no longer be seen as a benefit and responsibility only for the young. Formal education would no longer be seen as a 12-year or a 16-year experience, but could and should be a lifetime experience.