AARP Hearing Center

“Most bicycle crashes occur on the descents,” one of our guides had warned on our first day in Provence, France. Clocking all the gray heads on the tour bus, he hastened to add, “but you all aren’t in the crash demographic.”

“Who’s in the crash demographic?”

“Young males.”

It had been about 50 years since I’d been in the crash demographic; my dozen traveling companions and I had been friends since college in the early 1970s. The bus deposited us at Château de Mazan, a four-star hotel converted from the 18th-century mansion of the Marquis de Sade. After lunch we gathered in the parking lot, where our guides — Gawain Owen, 31, Max Moyles, 25, and Carolina Korody, 38 — were unloading bicycles from the roof racks of two large white vans. These were state-of-the-art $8,000 Trek carbon-fiber thoroughbreds, outfitted with Garmin GPS computers preloaded with our routes for the next six days, including the famously arduous climb up Mont Ventoux.

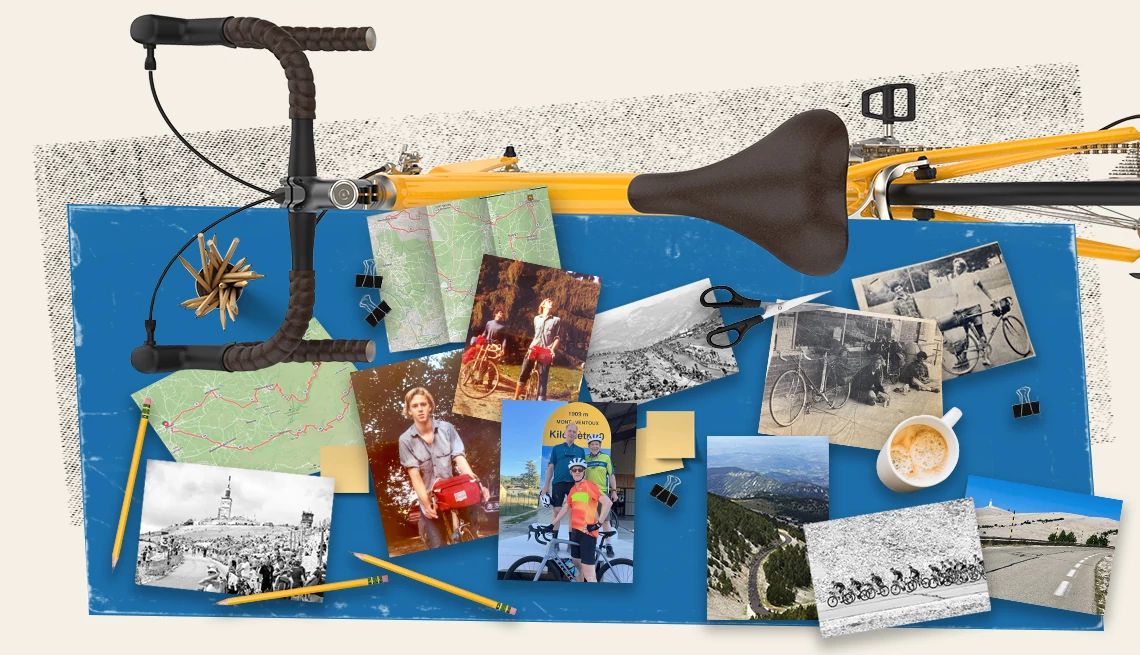

At home in New York City, I still ride the same bicycle I had when I was a senior in high school, a green steel-framed Bianchi Specialissma that was state-of-the-art in 1964. But what was flustering me even more than the profusion of futuristic innovations in bike technology was the power of the past to impose itself on the present. On one hand, I know it’s 2023 and I’m in France with people I’ve known for half a century. On the other hand, it’s also somehow the summer of 1972, and I’m about to ride my green Bianchi across the United States.

Like most 70-year-olds, I have undergone too many physical changes to mistake myself for a teenager: hairline, height, weight; that time-burnt look about the eyes. But time on a bicycle is not what it is anywhere else. When I took a wobbling lap around the parking lot to test the electronic shifters and disc brakes, I was flooded with a timeless joy. Here again was the sense of being on a machine that could carry one out of ordinary life and into the eternal present. On a bicycle, it’s not so much that you are young again as that you’re not any age at all.

In retrospect, the adventurous spirit that spurred my friend Steve and me across the United States in the summer of ’72 could easily be chalked up to adolescent overconfidence. Neither of us had a clue what we were getting into. We planned to camp wherever we could pitch a leaky orange tent. For food, we carried 3 pounds of dry-roasted soybeans. I had $150 in cash and no credit card. There were no cellphones, so no cellphone cameras — we had no camera of any kind. A whole summer passed without a selfie.

Equally unthinkable now is that we rode without helmets, sunscreen or dark glasses; we didn’t even have water bottles. No fingerless bike gloves to cushion the palms — Steve sometimes lost feeling in his hands from the pressure of leaning on the handlebars. No route guidance from digital GPS gizmos. We navigated with state maps picked up gratis at gas stations. Whenever we crossed a state line and got a new map, I mailed the old one home to my dad with our route marked in blue ink.

Dipping our right legs in the Long Island Sound, we set out the last week in June, with signs attached to our panniers that read, “Atlantic to Pacific.” Customs officers waved us into Canada at Niagara Falls and back into the U.S. at Port Huron, Michigan. Minnesota’s lakes bustled in the speedboat hoopla of high summer. In the tawny dry plains of South Dakota, the midday wind was so fierce we sometimes had to sit for hours in the shade of a storefront, waiting for it to drop. After a hundred-mile day across the badlands of western South Dakota, we splurged on dinner at a diner in downtown Belle Fourche — $1.50 for hamburgers, fries and milkshakes. Still ravenous, we went to the diner next door and ordered the same dinner again.

In Wyoming, we pedaled 73 miles on the only road available, Interstate 90, which that summer was so lightly traveled we hardly saw a car. In Idaho, the road slashed through flows of cooled lava. Eastern Oregon’s sweet tang of sage gave way to the soaked green odors of coastal rainforest and sawdust from lumber mills. When Steve and I got separated — a missed turn when I was too far out in front of him — we had to find phone booths and call our mothers collect, and have them call each other, then call us back to tell us where we were relative to each other.

After 3,825 miles and 45 days, we reached the far side of the continent and marked the milestone by dipping our left legs into the Pacific.

I had lost touch with Steve over the years, and he was not in the peloton of college friends when we all set out on our fancy bikes. The Day 1 itinerary promised a relatively gentle “warm-up” over the alluvial plains of the Vaucluse department. Indeed our Garmin-charted route on narrow backroads was easy at first, and I was carried along by the additional momentum of moral self-satisfaction. Of the dozen cyclists in our group, only Blaine, Marc and I had opted not to ride e-bikes.

After a few hills however, the e-bikers sailed past me, smiling and chatting. Even Marc and Blaine, who were making honest battery-free progress, were soon out of sight. Both had sensibly prepared for the week with a regimen of hilly training rides. Blaine had even packed a tube of mentholated “chafing cream,” which he said would be highly prized by anyone pedaling under their own power. When he thrust it at the camera during a group Zoom meeting before the trip, I had scoffed. Back in the day when I blah blah blahed across the United States, we didn’t mollycoddle our crotch areas with chafing cream.

But at the foot of the last hill that first day, my tailwind of self-righteousness faltered, as did my faith in the adage that anything worth doing entails struggle. The weather seemed frightfully hot. My hair under the helmet was drenched in sweat. I kept hearing raspy panting, which turned out to be coming from me and not a pursuing pack of stertorous French bulldogs. Aware of discomfort developing in select nether regions, I made a note to ask Blaine if I could try some of his wondrous chafing cream on Day 2.

I’d done a few training rides around Manhattan and the level terrain of eastern Long Island. But I’d mainly prepared by reading Cicero’s famous essay about old age. There were pearls to be found — “You do not miss what you do not want” — but frankly it was depressing. Even in 44 B.C., zealots were badgering slugabeds about how “exercise and temperance can preserve ... one’s pristine vigor.” The fallacy in Cicero’s argument, to me, was his assumption that in old age one would be wise enough not to squander precious bike-training hours reading hoary Roman orators.

The hill crested at last in the blond sandstone walls and terra-cotta roofs of Crillon-le-Brave. Our guides had set up racks where we could park our wheels while we replenished water bottles and enjoyed a view of farms spread out below the 17th-century village. It took some effort to hoist my leg over the seat and dismount. If this was supposed to be a warm-up ride, how was I going to manage the following day, when we were slated to grind out 46 miles on a road that threaded the spectacular gorge of the Nesque River? And a day later, what about Mont Ventoux, the mountain known as “the Beast of Provence” — a 35.7-mile route with 6,104 feet of uphill toil?

But the group was moving out, and suddenly all fretting was washed away by an exhilarating high-speed plunge down a road so narrow it sometimes resembled a bobsled track: gravity’s reward for the work of defying it. At every sandy curve or scattering of gravel, I thought, Oh so much could go wrong. But no, not that day. When we had finished the loop and were all back at the Marquis de Sade’s old den of iniquity, sipping a local Viognier, there was a buzz in the air — it might have been the euphoria of calamity averted. It could also have been the Viognier.

The following morning we rode up and around the 600-foot cliffs that form the gorge of the Nesque River. The road climbed the side of the limestone canyon, sometimes boring through tunnels or edging around precipitous drops. That we were ascending moderate grades of 3 to 4 percent only heightened the anxiety of the 10 percent grades awaiting the next day on Mont Ventoux.

After a group dinner, I toppled into bed but woke at 2:30 a.m. pickled in dread. At breakfast, Blaine, who seemed to have had no trouble riding battery-free up the Nesque Gorge, confessed he’d also lain awake, intimidated by the Ventoux itinerary. So intimidated he’d crafted special-interest legislation on his own behalf called SPARA.

“It stands for the Self-Protection and Recovery Act,” he said.

Under SPARA provisions, he planned to break the 21-mile journey from our hotel to the top of Ventoux into sections. He would bike the first 6.2 miles to the official start — Kilometer 0 — of the most popular way up the Beast. He would then continue biking the 4 miles to where a big bend marked the beginning of the really steep 6-mile section known as the Forest. SPARA granted Blaine the right to load his bike onto the van there and take a seat next to our guides, who would be driving around to set up snack stops and check on clients. Internal combustion would deliver him to Chalet Reynard, where a busy restaurant and parking lot marked the end of the Forest section. Blaine would then consider pedaling the final leg to the summit of Ventoux, but that go-no-go decision would depend on variables he believed would be premature to analyze over breakfast.

You Might Also Like

50 World Changers Turning 50

Books, films, historical events and more from 1974 that helped shape our world

Declutter Your Bucket List

As you age, you may want to consider reevaluating it based on health, finance and other changing needs

First Time Being Outhiked by My Kid

The tables have turned for Aileen Weintrab and her son, but an important realization was learned

More Members Only Access

Enjoy special content just for AARP members, including full-length films and books, AARP Smart Guides, celebrity Q&As, quizzes, tutorials and classes

Recommended for You