AARP Hearing Center

As a young man, Jim McFarland wasn’t all that interested in following his dad into the cobbling business.

“It felt like a family curse,” says the 60-year-old cobbler in Lakeland, Florida. “I saw the way my dad struggled, and his dad had struggled. It’s not an easy way to make a living.”

But today, McFarland is keeping his family's cobbling legacy alive through his surprisingly huge following on TikTok, the popular (and sometimes controversial) social media platform based on short-form videos. At the same time, his celebration of the ancient craft of repairing and preserving footwear is inspiring others to reduce wasteful buy-it-new consumerism.

Deep roots in cobbling

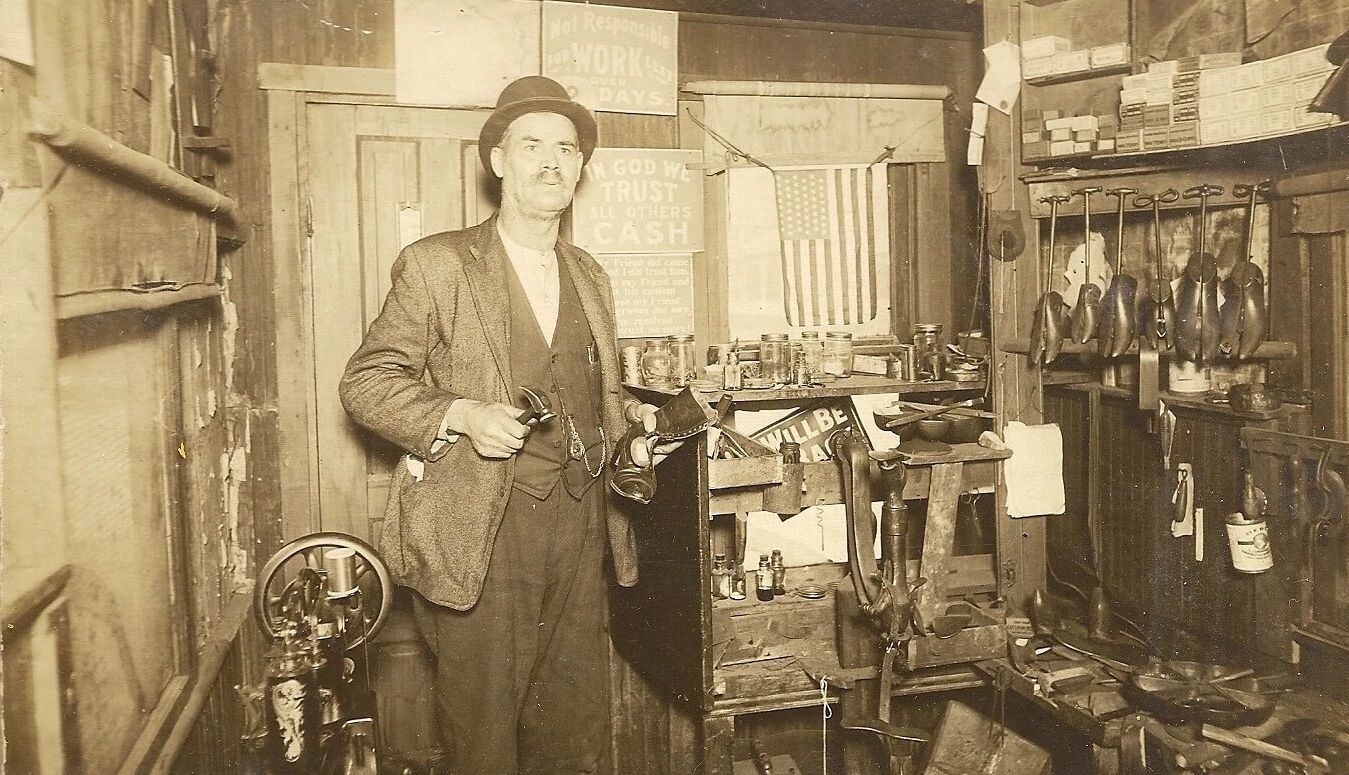

Shoe repair has been the McFarland family trade for well over a century. Jim McFarland’s great-uncle opened a cobbler’s shop in Anderson, Indiana, in the early 1900s. His grandfather did the same in Ohio in 1918, and McFarland’s father opened one in Lakeland in 1967. (He eventually owned three stores in the central Florida city.)

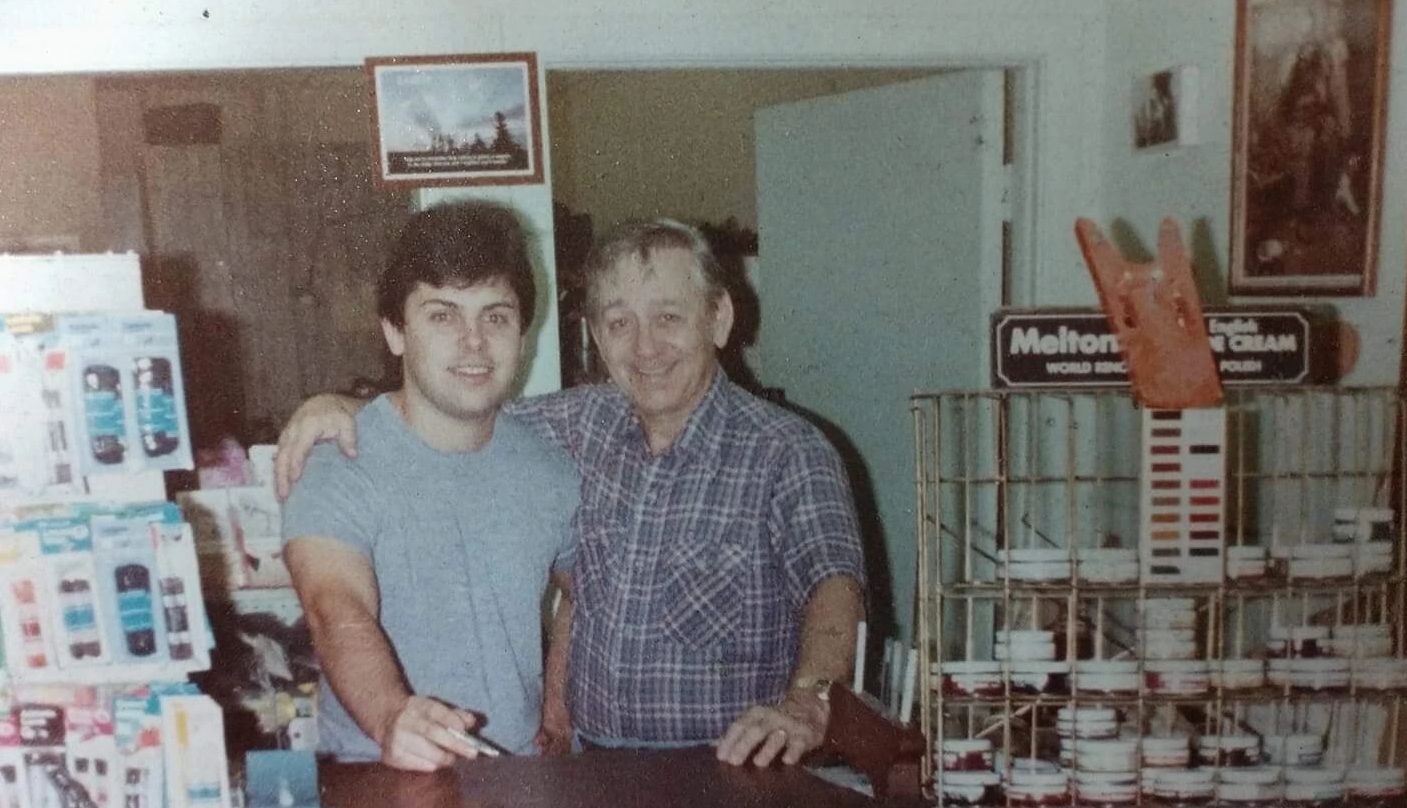

McFarland, however, had other plans. He attended Polk State University in Florida, pursuing a degree in psychology and hoping to someday coach high school football. But when he was 20, his dad got sick. He dropped out to lend a hand while his father recovered, and he took over one of the shops entirely in 1986. Today, it's the last McFarland family cobbler business still standing.

It wasn’t what he hoped to do with his life, but “I loved my dad more than anything in the world,” McFarland says. “I had no choice. I had to help him.”

Long before he found viral internet fame, McFarland was deeply immersed in the craft of shoe repair. In fact, he says he didn’t really need to be taught cobbling. He grew up working in his father’s shops, so helping with repairs came naturally.

“It’s like pinpointing exactly when you learned to speak English,” he says. “That’s the way I learned to repair shoes. I have no idea! It just happened.”

It’s a complicated craft, he says, involving “lots of machines and tools and nails and all kinds of instruments.” But the hardest thing he’s ever encountered as a cobbler was the day in 1987 after his dad passed away.

“He worked up to his dying day,” McFarland remembers. “He worked all day Monday, went to the hospital Monday night, and was gone Tuesday.”

McFarland had already agreed to take over the business from his dad, but that next morning felt especially difficult.

“Putting the key in the front door and turning it, and walking into the store for the first time in my life without him,” he says, his voice growing soft. “I talked to him every day, and then boom, he’s not there. It was hard.”

You Might Also Like

My Service Dog Saved My Life

Vet finds hope and healing through a local companion, communityYouthful Neighbors Bring Joy and Rejuvenation

A retired journalist welcomes young kids (and their parents) to the areaThis Mom Raised More Than 40 Kids

As an empty nester, Emma Patterson became a dedicated foster parentRecommended for You