AARP Hearing Center

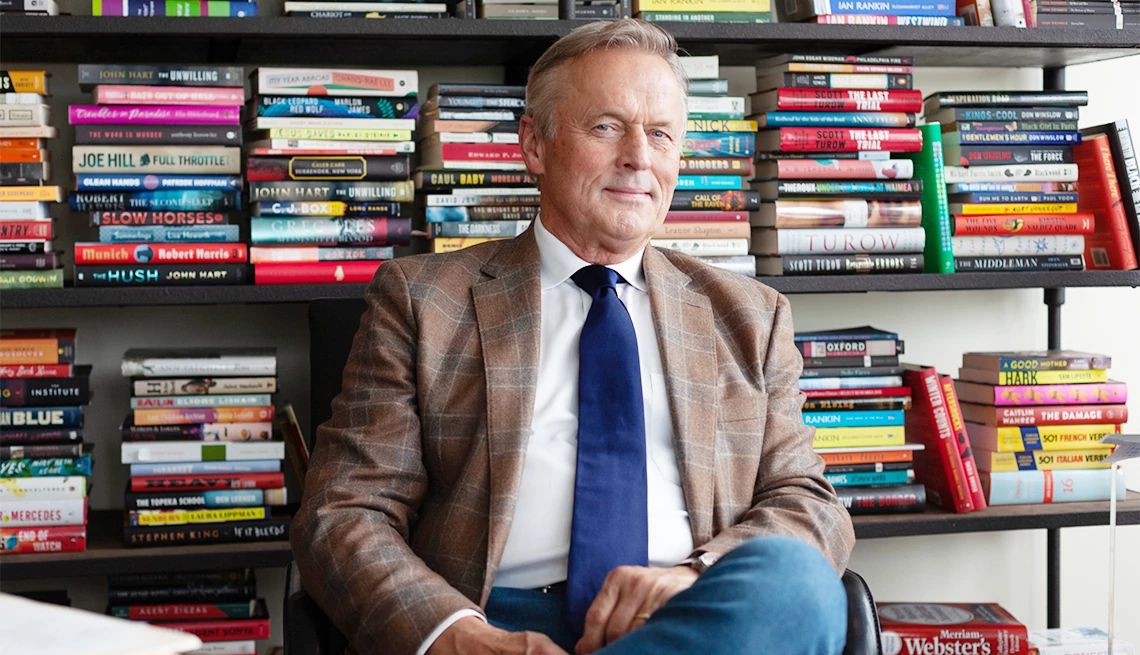

John Grisham, a former lawyer, has been a wildly successful novelist since his first book, A Time to Kill, came out in 1989. But he’s always turned to the legal system to inspire and inform his work.

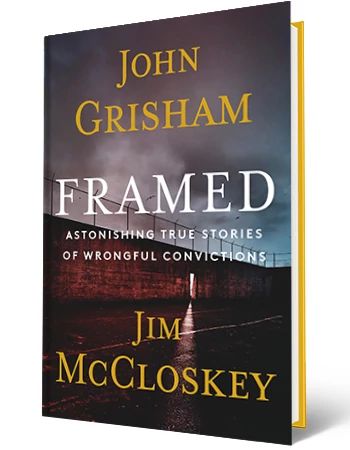

That’s certainly true of his new book Framed: Astonishing True Stories of Wrongful Convictions (Oct. 15), which highlights 10 stunning cases of people whose lives were upended by cops, prosecutors and other officials who, the book argues, twisted or withheld facts or straight-up lied to get the convictions they wanted. He cowrote it with Jim McCloskey, founder of Centurion Ministries, devoted to freeing the unjustly convicted.

We spoke with Grisham about his book and the writing life.

The interview has been edited for space and clarity.

Why this book, at this time?

I’ve been infuriated for 18 years now, ever since I wrote The Innocent Man 0in 2006 (exploring how four men were unjustly implicated in the grisly murders of two women in a small Oklahoma town in the 1980s), and I realized how many innocent people are in prison — and there are thousands of them. You study these cases, and they’re hard to believe, that the police and prosecutors can screw up so badly. These are not all innocent, honest mistakes. There is a lot of deliberate lawbreaking, deliberate malfeasance and deliberate bad behavior in every one of these cases.

What would it take to stop most wrongful convictions?

There are about four or five things that would prevent most wrongful convictions. For example, in most of these cases, you have a jailhouse informant, who is nothing but a con man who’s been paid by the cops and prosecutors to give false testimony against the accused.… So I would eliminate snitch testimony. I would require the police to film all interrogations. That would probably eliminate almost all false confessions.… And I’m from Mississippi — we elect every judge down there, and most states do that. So you’ve got a bunch of politicians who are on the bench. It’s a bad system.

You Might Also Like

Is Nicholas Sparks as Romantic as His Novels?

‘The Notebook’ author discusses life, love and his new book, ‘Counting Miracles’Check Out AARP’s Favorite Books of 2024 (So Far)

Our books editor shares her top pick and nine other fiction and nonfiction standoutsThe 25 Best True-Crime Stories

Books, shows and podcasts so good it’s criminalRecommended for You