AARP Hearing Center

Sylvia Abbeyquaye, the director of nursing at a 120-bed nursing home in Brookline, Massachusetts, tested positive for COVID-19 just a few weeks into the pandemic. The virus severely inflamed her lungs, landing her in the hospital with bilateral pneumonia. “I didn’t think I was going to get through it,” she says.

Her workplace, meanwhile, kept calling. When was she coming back? It was April 2020, when the virus was spreading and more workers were out sick. More residents were dying. After six weeks off, Abbeyquaye, 48, returned to help combat the chaos. “But I never was the same again,” she says. “I was completely exhausted, burnt out and just down. ... I couldn’t take it.”

She handed in her letter of resignation without another job lined up. “I just left,” says Abbeyquaye, who had worked in U.S. long-term care since emigrating from Ghana more than 20 years ago. “I didn’t know what the future was.”

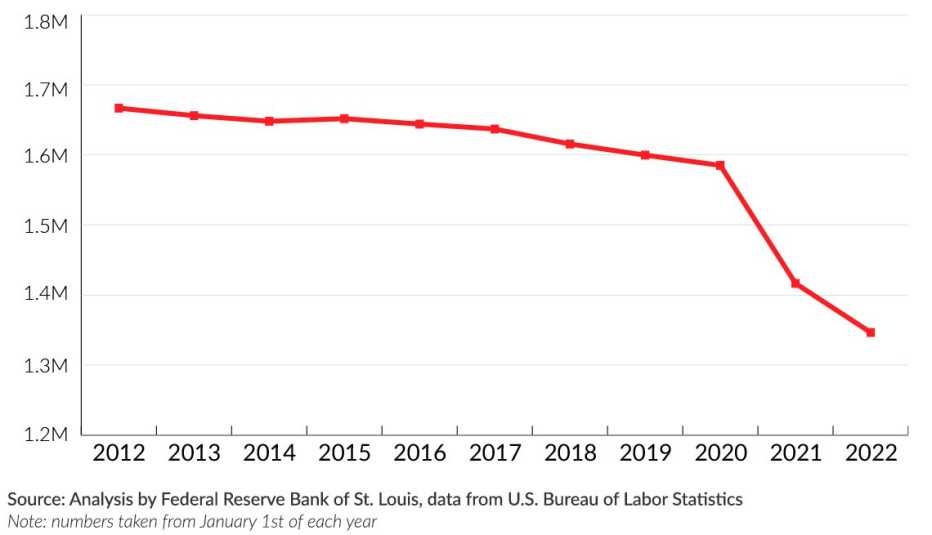

The nation’s nursing home industry has shed roughly 235,000 jobs since March 2020, according to an analysis of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data. That’s roughly 15 percent of the nursing home workforce, gone. The figure far outpaces the numbers lost in other health care sectors, which have also seen steep drops.

The Decline of Employees in U.S. Nursing Homes

And it’s not because demand for workers has decreased. Every month since summer 2020 — when the federal government began collecting COVID-19 data from nursing homes — has seen more than a fifth of nursing homes nationwide without enough workers, according to an analysis by AARP. Shortages have been at their worst this year, peaking between mid-December and mid-January, during the omicron surge, when 39 percent of nursing homes reported a lack of nurses and/or aides. In Alaska, Minnesota and Washington, over 70 percent of facilities reported staffing shortages.

Workers say their exits are driven by dangerous working conditions, poor pay and benefits, limited opportunities for advancement, burnout and the respect deficit for their profession. Those issues were intensified by the pandemic, but they’re long-standing and deep-seated across the industry. “The foundations were so weak,” Abbeyquaye says. “COVID was just the last straw.”

Some workers have shifted to other health care roles in hospitals or private homes. Many have become travel nurses, who typically work temporary assignments in various short-staffed facilities for higher pay. Others have left for higher wages at places like Amazon and McDonald's. Some had to take on caregiving responsibilities at home or have opted for early retirement. Many immigrant workers have returned to their home countries. And many, like Abbeyquaye, just quit.

As staff flee, the health of nursing home residents has deteriorated, according to an analysis of federal data by the National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care. It found that in addition to the thousands of COVID-19 deaths among residents — now totaling some 170,000 — bedsores, weight loss, depression and the use of antipsychotic medication all rose during the pandemic.

The physical and mental health of workers is also deteriorating as they try to carry the excess load. A survey of nurses in hospitals, long-term care facilities and other health care settings by national staffing agency Incredible Health found that roughly a third of nurses said they very likely will quit by the end of this year, primarily because of stress and burnout.

The staffing crisis is forcing a growing number of nursing homes to halt admissions or close completely. A poll by LeadingAge, a national association representing nonprofit senior care providers, found that more than a third of its members are unable to admit new residents or serve new clients because of staffing challenges. And up to 40 percent of nursing home residents are living in facilities that are financially at risk of closure in 2022, according to Clifton Larson Allen, a wealth adviser for the long-term care industry.

The rapidly growing population of older adults, meanwhile, is expected to drive demand for nursing home care even higher in years ahead. The number of adults age 85 and older is projected to reach 19 million in 2060, up from 6.5 million in 2016.

“Many people would say that ‘crisis’ isn’t a strong enough word” to describe the shortages, said David Grabowski, a Harvard Medical School researcher who studies the economics of long-term care. “With the pandemic, we have a crisis on top of a crisis. ... Someone has called the current situation a staffing apocalypse.”

‘Living beyond paycheck to paycheck’

U.S. nursing homes were difficult places to work even before COVID-19. Staff turnover was already “astronomically high,” says Ashvin Gandhi, a health economist at UCLA and coauthor of a national study that found the median annual turnover rate for nearly all U.S. nursing homes in 2017 and 2018 was 94 percent. To maintain a staff of 100 employees over a year, a facility would have to hire 94 new workers annually.

That’s largely because certified nursing assistants (CNAs), who make up the largest group of nursing home employees, are among the lowest-paid workers in the health care industry, with a median annual income of roughly $30,000. Many are hired as independent contractors or part-time employees and don’t qualify for paid time off or health insurance. They often juggle multiple jobs to make ends meet; most who aren’t are providing unpaid care for family members, a recent study found. A disproportionate number are female, Black and immigrants.

CNAs provide around 90 percent of direct patient care in nursing homes: lifting, bathing, toileting, dressing and feeding. Before the pandemic, they were 3.5 times more likely to be injured on the job than the typical U.S. worker. Decades of chronic understaffing has meant unpredictable schedules, regular overtime and little support for training and professional development.