AARP Hearing Center

Feeling indifferent and unmotivated? Lethargic and unfocused? You may be languishing.

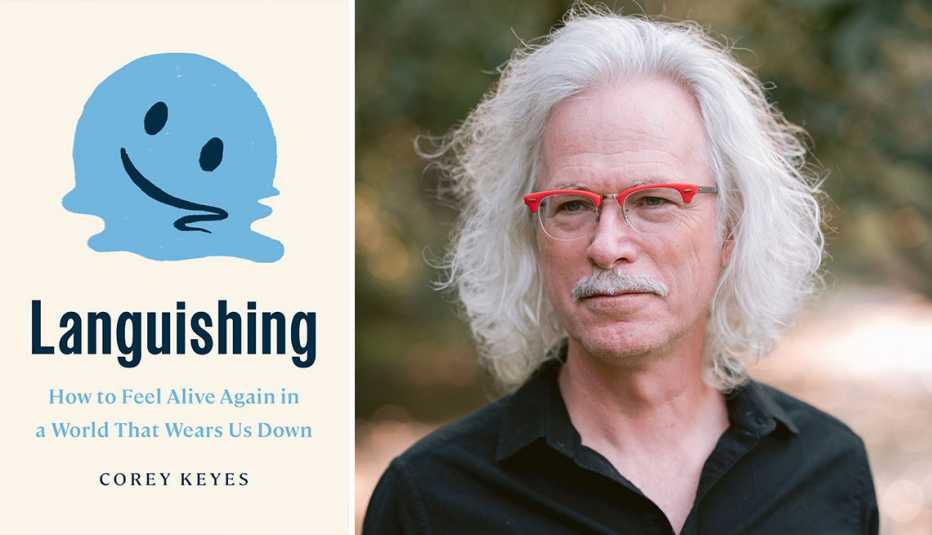

So writes sociologist and Emory University professor emeritus Corey Keyes, whose new book, Languishing: How to Feel Alive Again in a World That Wears Us Down, explores why so many of us feel this “sense of low-grade mental weariness,” as he puts it, and suggests ways to transform languishing into flourishing.

“Languishing goes well beyond single-word descriptions of ‘blah’ or ‘meh,’ ” Keyes, 61, told AARP in a recent interview. “It is the absence of some very fundamental or important things that make life worth living or meaningful, or make you feel like you matter in the world.”

Among the symptoms:

- You feel emotionally flattened. It’s hard to muster excitement for upcoming milestones and events.

- Things seem increasingly irrelevant, superficial or boring.

- You regularly experience brain fog (for example, standing in the shower and trying to remember whether you’ve washed your hair).

- You procrastinate on tasks as a why-try-anyway attitude sets in.

- You feel restless, even rootless.

Languishing is not the same as depression, Keyes notes. Depression involves a daily or almost-daily sense of hopelessness or sadness for at least two straight weeks, often accompanied by crying spells, excessive or inadequate sleep and suicidal thoughts. Millions of people are languishing who don’t meet those criteria.

Although languishing is obviously not new, the pandemic intensified those feelings worldwide. In 2021, a New York Times story by organizational psychologist Adam Grant on languishing (“There’s a Name for the Blah You’re Feeling: It’s Called Languishing”) became the news site’s most-read story of the year.

“People had significant losses of the things that make their life meaningful, which made it hard to have purpose, belonging, contribution, a sense of acceptance,” Keyes says.

More From AARP

6 (Non-Drug) Ways to Fight Depression

There are options to try, with or without medication9 Essentials for a Happier Life, According to Oprah Winfrey

Her new book ‘Build the Life You Want’ with Arthur C. Brooks offers an action plan for ‘happierness’

The Truth Behind 8 Happiness Myths

From money to genetics, here’s what scientists know about what actually makes you happy

Recommended for You