AARP Hearing Center

Imagine John Lennon at 80. The smart Beatle, the funny one, the Liverpool lad whom young guys wanted to be and moms worried about. Forty years after his death at age 40, we mark the date and celebrate the musical genius who gave peace a chance.

Alice Cooper

I remember painting a house when I was 15 years old and the radio was always on. We were used to the Four Seasons and the Beach Boys, and all of a sudden we hear, “She loves you, yeah, yeah, yeah!” and, “I wanna hold your ha-a-a-and.” These Beatles songs were different than anything we'd ever heard. I'm not kidding when I say it changed our whole direction in life. My three best friends and I instantly said, we need to start a band! John, Paul, George and Ringo — they basically started every band you hear today.

John and I became great friends later on, even though we were polar opposites. He was outspoken and loved politics. I loved horror and comedy and thought music should be an escape from current events. But what fun we had. We were like two midnight vampires at clubs like Max's Kansas City in New York and the Rainbow in L.A. Harry Nilsson would be there, too, and Micky Dolenz from the Monkees, and Bernie Taupin, but John was the most electric, the most fascinating, the James Dean of rock. The one unwritten rule we had tells you what an interesting musician John was: We never talked about music!

The day he died I had the house at the top of Benedict Canyon in L.A. My next-door neighbor was Elton John. I had one of those early big-screen TVs, and some guys from my band were writing a song with me when the news came on. John Lennon is dead. I swear, there was like a vacuum in the room. Everybody just got up and left and didn't say a word. Honestly it was like your parents dying. Like, “Hey, your mom and dad just got killed in a plane crash.” You couldn't digest it.

The next day, almost every musician I knew started carrying a piece. I had a little .22-caliber Walther PPK, and everybody had some sort of weapon just in case. We didn't know if John's death was part of a conspiracy or what. Because, gosh, if they could get John Lennon, the high priest of rock ‘n’ roll, they could get any of us. Our innocence was gone. The loss was irreplaceable. That was the day the music died.

Jane Pauley

If you look on YouTube you'll find the NBC special on John Lennon I anchored that week. Professional Jane was really trying to hold it together, but the girl inside me was losing it. I remember on the Today show the morning after John died, Tom Brokaw and I ended with an extended montage under the song “Imagine.” The second we wrapped, I started sobbing. An AP photographer captured the moment — me with my head in my hands, Tom looking like he didn't know what to do when a woman is crying.

I was in eighth grade when I saw the Beatles at the Indiana Fairgrounds Coliseum, though I couldn't actually see or hear them. I was in the back of the rafters and the screaming was nonstop. The day John died, I felt my youth had been put in a box and that box was closed. The generational attachment was that profound.

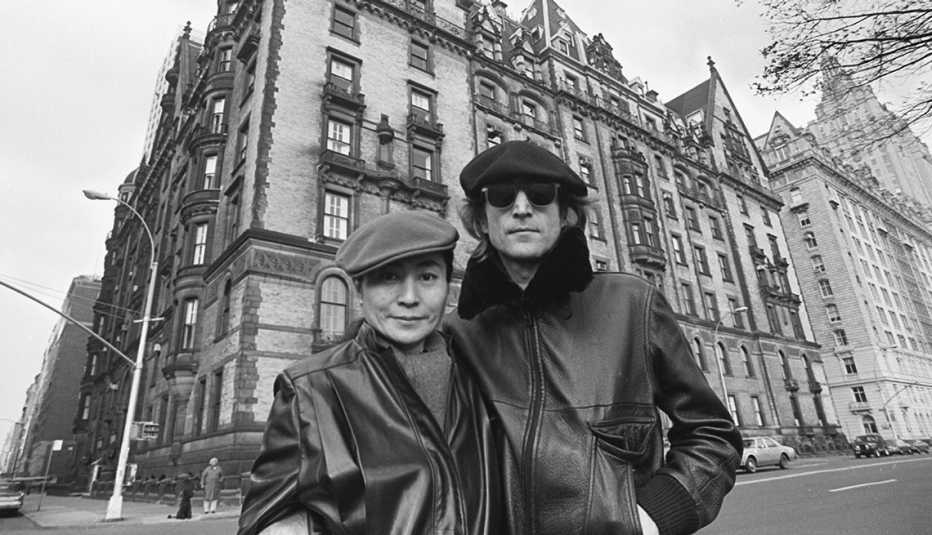

That night in 1980 feels so long ago now. But the memory is so precious. My husband, Garry [Trudeau, the “Doonesbury” creator], and I agreed recently that the closest thing we have to “our song” is John Lennon's “Woman.” I can't drive by the Dakota to this day without thinking about it.

Jann Wenner

I always thought of the Beatles as one person in four parts, and John was the brains, the political heart, the conscience of a generation that wanted peace and love. He shaped pretty much everything for me. His picture was on the very first cover of Rolling Stone, and he became the guiding spirit not just for the magazine but for the entire era. That whole attitude of freedom and having fun and excitement and joy; his sardonic quality and his take on life about how square and stupid so much of our culture was — he embodied what was going on in society.

In the ‘70s John was such a towering figure that it was almost like hanging out with a god. I was a lowly magazine publisher. He was a Beatle. When you'd spend time with him, you had to be on top of your game and quick-witted. He was so sharp, so smart, so funny. His energy could be scary. After an evening with him, I'd walk away and think, My God, did that just happen?

We were doing a photo shoot with John and Yoko that whole week [leading up to his death] for the release of Double Fantasy. Annie Leibovitz was in their apartment that day when she took that powerful, iconic image of John wrapped around Yoko. I think it was John's idea to do that, and it was so representative of their relationship, of birth, of life, of death.

I heard about his death on the news. The feeling went from sad to horrifying to tragic. I cried a lot. The next morning I came into the Rolling Stone office late and closed my door. People knew I was upset, but we knew we wanted to record the moment with an issue that paid homage to this great man of our time. He combined all the elements of a superman for people my age: humor, wisdom, ambition, strength, talent. And he was a great rock ‘n’ roller.

It's hard to imagine him now. Would he be the same old eccentric, curmudgeonly man? Maybe. Creative? Wiser? Who knows? He still lives inside my head with his lyrics. There are so many great lines but the ones that surface, as I get older myself, are from “Help!"

"When I was younger, so much younger than today / I never needed anybody's help in any way. / But now these days are gone, I'm not so self-assured. / Now I find I've changed my mind and opened up the doors."

More on entertainment

The Story Behind the 'Abbey Road' Cover

50 years later, the iconic image endures

Ringo Starr Mines Beatles Vault on New Album

Unreleased Lennon track highlights 'What's My Name'Rosanne Cash: My Favorite Beatles Tune

Hint: John Lennon wrote it when he was 24