AARP Hearing Center

The 31 songs on the expanded version of Taylor Swift’s new The Tortured Poets Department album rehash breakups, nurse grudges and revel in fresh romance. America’s favorite prom queen doesn’t stray far from her signature confessional pop tunes littered with guess-who clues about ex-boyfriends.

But she’s also showing off her increasingly scholarly report card. The 34-year-old megastar has alluded to highbrow writers from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Robert Frost in earlier songs, but the heartbreak-heavy Tortured is particularly fat with literary and grownup cultural references that may fly over the heads of the younger Swifties.

Tortured, Swift’s ninth album in five years (including four rerecorded Taylor’s Version releases), sold 1.4 million copies its first day and racked up 490 million streams in three days, according to Billboard. Media and fans are buzzing about the album’s transparent allusions to such discarded partners as actor Joe Alwyn and British musician Matty Healy, as well as current flame Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce.

Tortured is steeped in the romantic melodrama that unfolded during her “Eras” tour. Less obvious and more unexpected are the nods to earlier periods.

Old English

The album kicks off with a synth pop downer about marital misery called “Fortnight.” A good portion of Swift’s fans are likely more familiar with the postapocalyptic zombie video game Fortnite, played by 650 million users, than this antiquated British term for two weeks (literally fēowertīene niht, or 14 nights), which was popular from around 400 AD until the 1920s.

The Chelsea Hotel

“This ain’t the Chelsea Hotel,” Swift sings in the album’s title track. The storied New York City hotel, built in the mid-1800s, was a creativity crossroads frequented by writers, poets, musicians and artists. It’s where Bob Dylan crafted Blonde on Blonde, Andy Warhol filmed portions of Chelsea Girls, Arthur Miller wrote After the Fall, William S. Burroughs penned Naked Lunch and Leonard Cohen bedded Janis Joplin, then wrote the tune “Chelsea Hotel #2.” Among its regulars and residents were Thomas Wolfe, Jack Kerouac, O. Henry, Eugene O’Neill and Allen Ginsberg.

Dylan Thomas

Dylan Thomas (from whom Bob took his stage name) also stayed at the Chelsea Hotel. In “The Tortured Poets Department,” Swift takes a swipe at Healy, comparing him unfavorably to the hugely popular Welsh poet, whose most familiar work is 1931’s “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night.” Thomas died of alcoholism; Healy has been open about his recovery from heroin addiction. She sings, “I laughed in your face and said, ‘You’re not Dylan Thomas.’ ”

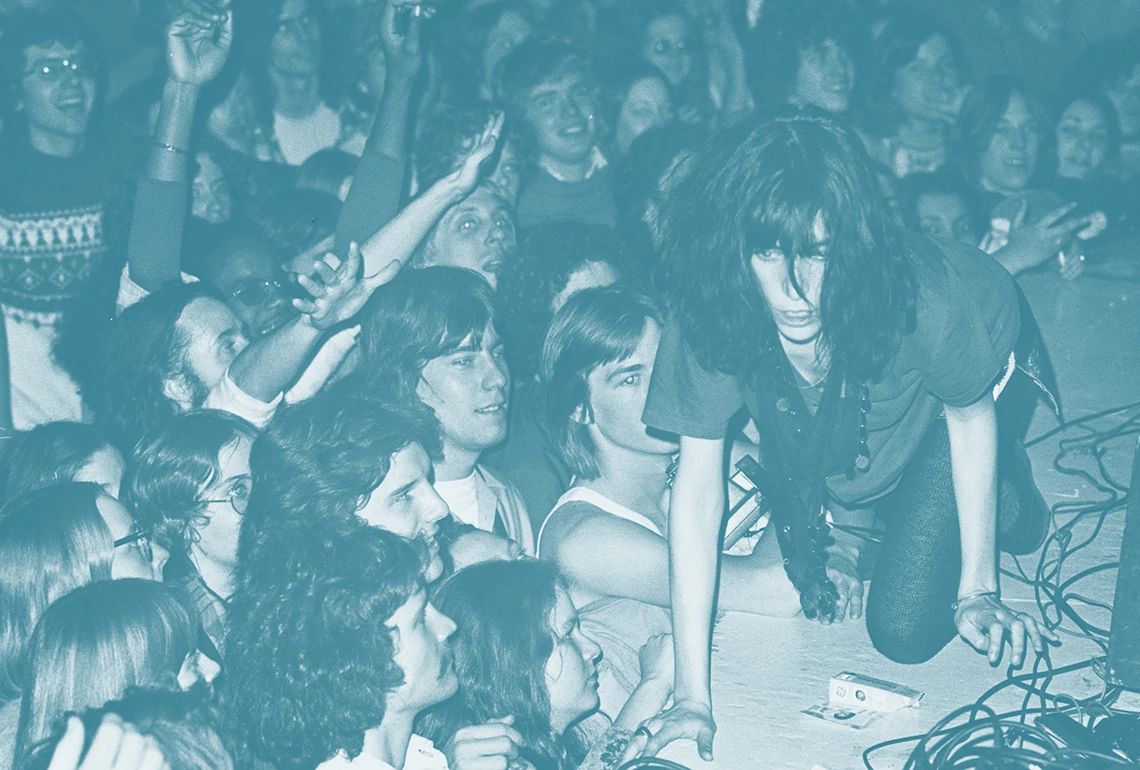

Patti Smith

In the same song, Swift admits, “I’m not Patti Smith / This ain’t the Chelsea Hotel / We’re modern idiots.” Despite Swift’s massive success, few will argue that point. Smith, 77, has long been revered for her punk music, poetry and bestselling memoirs. Oh, and she lived for a time in the Chelsea’s smallest room with photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, another name that many Swifties might have to google.

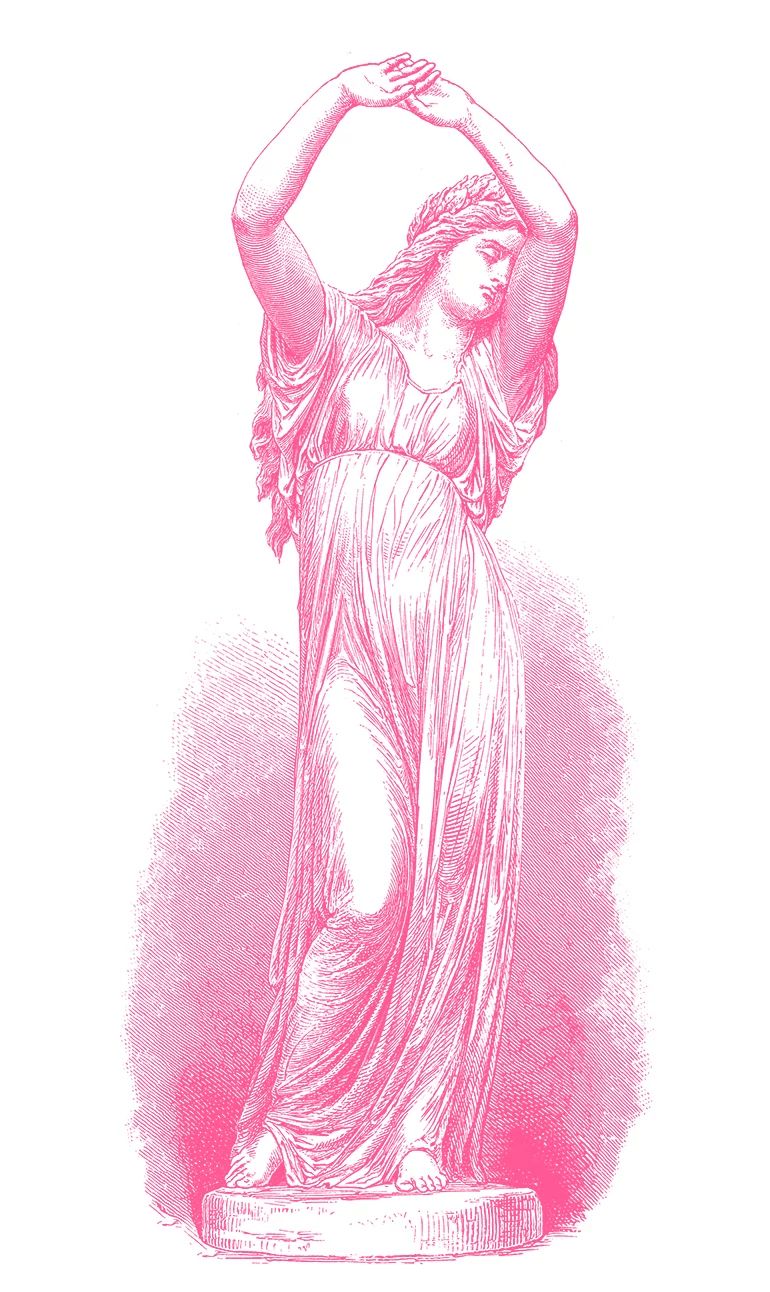

Cassandra

Swift addresses media glare and the perils of public life in “Cassandra,” a clear reference to the daughter of the king of Troy in Greek mythology. Apollo gave Cassandra the power of prophecy, but when she rejected him, he cursed her so nobody would believe her omens. The song’s chorus: “So they killed Cassandra first ’cause she feared the worst / And tried to tell the town / So they filled my cell with snakes, I regret to say / Do you believe me now?”

More From AARP

Get to Know the Banjo Player on Beyoncé’s First Country Song

46-year-old Rhiannon Giddens shares her musical journey, from North Carolina to the BeyHive

Sarah McLachlan: ‘I Feel Revitalized. I Feel Like I Still Have a Lot to Say.’

Grammy-winning singer-songwriter embarks on North American tour, is working on new album

Sheryl Crow Talks Her Comeback Album ‘Evolution’

The songwriter explains her life’s winding road and new musicNPR Music Guru Bob Boilen on the 6 Artists You Should Know

Boilen retired in 2023 but continues to spread his love of music

Recommended for You