AARP Hearing Center

What do you think of when you hear the words “Tommy John”? If you’re a baseball fan of a certain age, you might think of the four-time All-Star pitcher who won 288 major league games. That lucky fellow is me.

But to most Americans, the words “Tommy John” mean something different: surgery. In particular, the once-revolutionary elbow surgery that saved my career in the mid-1970s, a procedure that’s now so common that even people who’ve never heard of me have heard of the operation that bears my name.

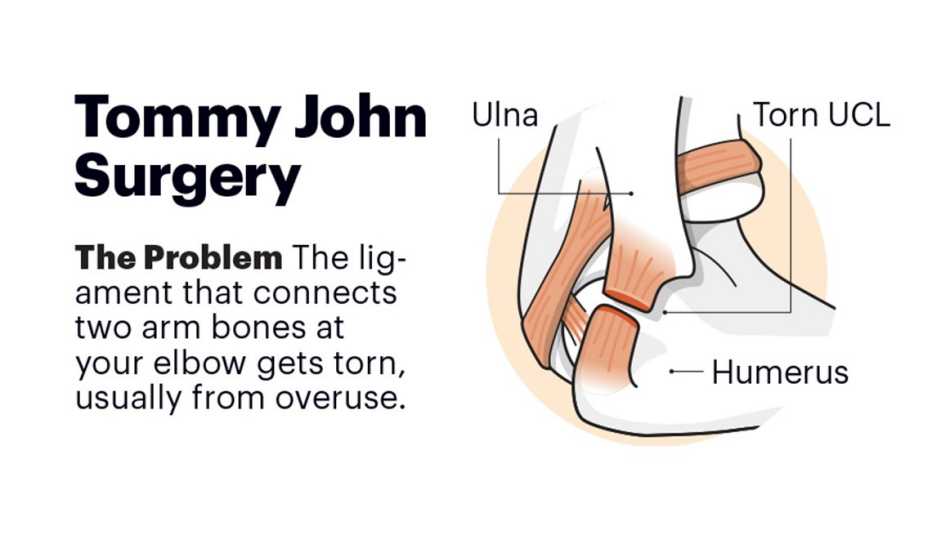

In 1974, when I became the first person to have a damaged ligament in my elbow surgically reconstructed, I was thrilled. It saved my pitching arm halfway through my 26-year baseball career. I had no idea it would be called Tommy John surgery until a decade later, when the surgeon who pioneered the method, Frank Jobe, told me it was easier when describing the technique — ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) reconstruction — to simply say, “You know, that surgery I did on Tommy John.”

It doesn’t bother me to watch my legacy being upstaged by an operation that has saved plenty of ballplayers’ careers. What does bother me is that my name is now attached to something that affects more children than pro athletes. I was in my 30s and playing major league ball for nearly a dozen years before needing the operation. Today, 57 percent of all Tommy John surgeries are done on kids between 15 and 19 years old. One in 7 of those kids will never fully recover.