AARP Hearing Center

Remember the Ice Bucket Challenge? It’s been 10 years since social media feeds were saturated with videos of people willingly having large buckets of ice water dumped over their heads to raise money for ALS research.

More than 17 million people took the challenge in 2014 to speed research on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, helping raise $115 million for the ALS Association. The viral fundraiser nearly doubled the association’s annual research funding, expanding support to more than 500 research projects around the world.

AARP Membership— $12 for your first year when you sign up for Automatic Renewal

Get instant access to members-only products and hundreds of discounts, a free second membership, and a subscription to AARP the Magazine.

ALS is a progressive disease with no cure. It is also rare: About 30,000 people in the United States have it. Conditions that affect so few people seldom get that kind of public attention, or that kind of money. The Ice Bucket Challenge “brought a lot of attention to a rare disease and to the gaps that existed,” says Kuldip Dave, senior vice president of research at the ALS Association. “It brought focus to a disease that was, frankly, unknown.”

What is known about ALS? And has the Ice Bucket Challenge made a difference?

What is ALS?

You might know ALS as Lou Gehrig’s disease, named for the New York Yankees first baseman who retired after developing the disease in 1939 at age 36.

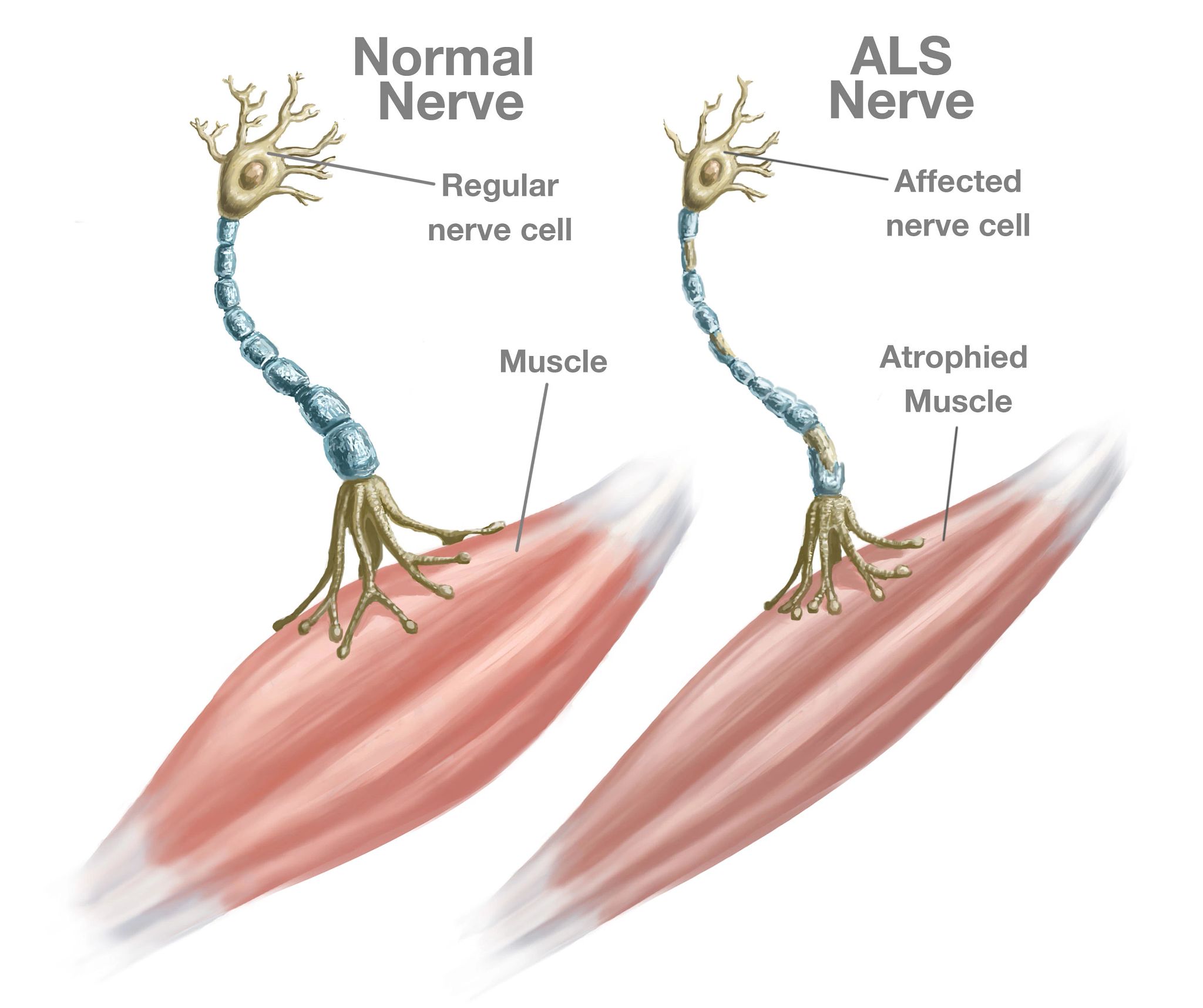

In ALS, nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord that control muscle movement and breathing deteriorate and die. Those cells, called motor neurons, can no longer send messages between the brain and the muscles, so the muscles weaken, start to twitch and waste away, or atrophy. Eventually, the brain cannot control voluntary muscle movements such as walking, talking, chewing and, eventually, breathing.

“These motor neurons start slowly dying. That’s why you slowly get weak. It doesn’t happen abruptly, like with an acute injury. But why these cells start dying? Honestly, we don’t fully understand,” says Jeffrey Rothstein, M.D., director of the Robert Packard Center for ALS Research at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

What are the symptoms of ALS?

Weakness in an arm or leg, trouble swallowing or slurred speech are the most common first symptoms. The weakness may be preceded by twitching or cramps in the arms, shoulders, legs or even the tongue. But these aren’t the only possible early symptoms. The way ALS first shows up varies a lot from one person to another.

Symptoms of ALS

- Weakness, muscle atrophy, twitching or cramps in muscles of arms or legs

- Slurred speech, difficulty chewing or trouble swallowing

- Trouble walking or doing daily activities

- Tripping, falling or clumsy movements related to the hands or feet

- Laughing, crying or yawning at inappropriate times

“For some people, it might be only their arms that are weak for years before the legs get weak,” Rothstein says. In others, he says, muscles used for breathing, chewing and speaking are damaged early on, and the arms are affected very slowly.

ALS usually doesn’t affect the senses, including the ability to taste, smell, touch and hear. People with ALS usually remain able to reason, remember and understand, which means they are aware of the progressive loss of function. Less often, people with ALS experience changes in their behavior or the way they think or act. This happens to some degree in about half of people with ALS, according to the most recent diagnostic criteria for the disease. These changes are often mild. About 8 to 9 percent of people who experience these cognitive changes will develop dementia and no longer be able to make decisions about their care.

More From AARP

Take the Cognitive Assessment

Find out how you perform today in five key areas, including memory and attention

Can My Spouse, Who Has ALS But isn’t 65 Yet, Get Medicare?

People with Lou Gehrig’s disease can qualify for Medicare early

First Steps to Treating Dementia May Lie in Related Diseases

ALS research could lead to dementia drugsRecommended for You