AARP Hearing Center

Over the last 40 years, the average home in the United States has increased in size by more than 1,000 square feet, essentially doubling the amount of living space per person since 1973.

But a decade ago, in the midst of the housing boom and explosion of outsized, luxury home construction in American suburbs (i.e., the "McMansion"), a quieter, smaller movement began to gain attention.

The idea of building quality homes of less square footage but with truly used spaces began to take hold. This concept, sometimes referred to as the "Not So Big House" approach to residential design has ignited a trend that reflects the state of the U.S. economy, the still-struggling housing market and a growing conservation ethic to reduce and reuse. Welcome to the Tiny House.

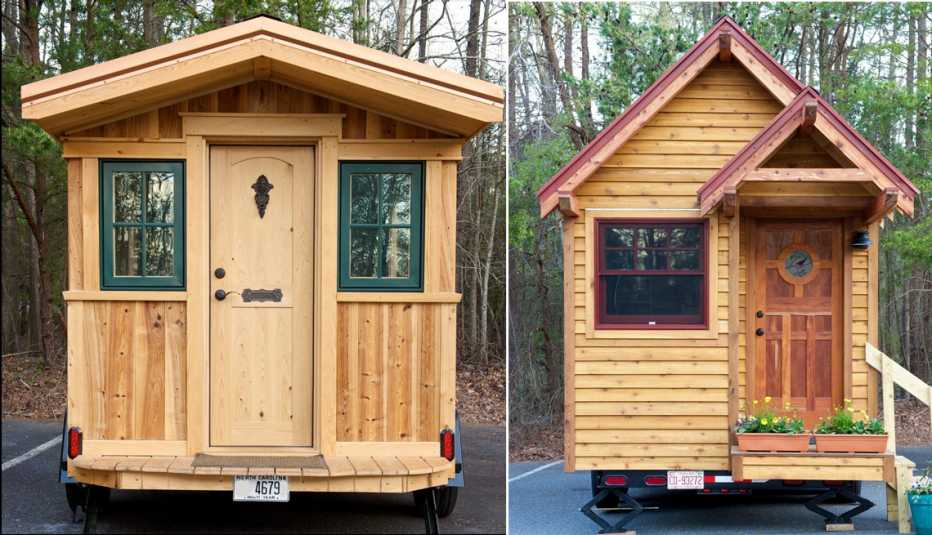

A so-called "Tiny House" makes the average 2,600 square foot American home look and feel like a home twice that size. These micro homes measure, on average, from 100 to 400 square feet, but they can be as small as 80 square feet or as large as 700 square feet. Often resembling studio apartments, tiny homes can be crafted in many styles and customized to personal tastes.

Although these houses are small, they are big enough to include the needed amenities of a home. There’s a sleeping area, a bathroom, a modern kitchen, storage and spots for eating and relaxing. In most cases, the structures are aesthetically-pleasing, often so much so that they’re worthy of photo spreads in glossy housing magazines. While most tiny home owners live alone, the structures can be built to accommodate couples and even families.

Unlike typical houses, these homes are mobile — some even stay on their wheels — and can either work on the utility grid or be completely self-sustaining.

The idea of living small, really small, is catching on. Tiny house communities are multiplying, and approximately two out of every five tiny house owners are over age 50. Tiny house converts and fans are hosting events and how-to workshops across the country. And builders and designers are catering to the demand. Tiny homes provide a viable living option for some older adults and offer communities new ways to think about housing.

Smaller Spaces = Less Work and Bigger Savings

"The benefits of tiny homes are obvious," says George Chmael, the CEO of Council Fire, an Annapolis, Maryland-based consultancy that advises nonprofits, corporations, governments and communities on sustainable building practices. "There's reduced maintenance, a reduced financial burden and added movability and mobility for a change of circumstances."

While each of those benefits is helpful to any homeowner, they're especially valuable for an older adult who isn't up to taking on major home maintenance work, is on a fixed budget and both wants and may need the flexibility to adapt to whatever the future brings.

With many Americans spending one-third to more than half of their income on housing, living small uses significantly less of a paycheck or savings for putting a roof over one's head. According to a frequently-cited infographic from The Tiny Life, a website of resources devoted to living small, 68 percent of tiny house owners have no mortgage compared to 29.3 percent of all U.S. homeowners.

The average cost of a standard-sized home in the United States is $272,000 (plus an additional $200,000 or so if the price comes with a 30-year mortgage at current interest rates). The average cost of a tiny house is $23,000 if built by the homeowner. The price tag typically doubles if a builder is used.

Age-Friendly Options

Tiny houses can also solve difficult, and often prohibitively expensive, space quandaries.

- A tiny house can serve as an accessory dwelling unit (e.g. in-law apartment, "granny flat") that’s literally parked in a backyard

- A tiny house can be a specially tailored space for a relative with special needs

- With a tiny house structure a person can park his or her office in the yard — and eliminate a commute

- A tiny house can be a starter home for grown children or grandchildren who may not be able to afford other options

- A tiny house can serve as a home on a property a person owns but can’t build on, or it can serve as a home while a permanent home is renovated or built

- A tiny house can become the primary living quarters for a homeowner who has a no-longer affordable mortgage by enabling the owner to live on the property while renting out the larger house to cover the mortgage

- A tiny house can be a private living space for a live-in caregiver