I was escorted off campus that scary night, and Hamp and I were suspended under the ruse of "for our own safety," but we were soon readmitted and lived the next two years in relative quiet. Determined not to be bound by limits, I made a few white friends, mostly journalism students, including one who later became my first husband. By then, young people across the South were sitting at lunch counters, marching in the streets, challenging segregation at the coal face. (Three years later, during the tide-turning Freedom Summer, hundreds from the North would join them in a "righteous crusade" to win black Mississippians' right to vote — a crusade that would lead to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.) So in quiet solidarity, I joined an upstart black newspaper headed by activist M. Carl Holman, with Julian Bond as managing editor, and spent weekends and holidays writing stories about Atlanta's often-jailed yet steadfast demonstrators.

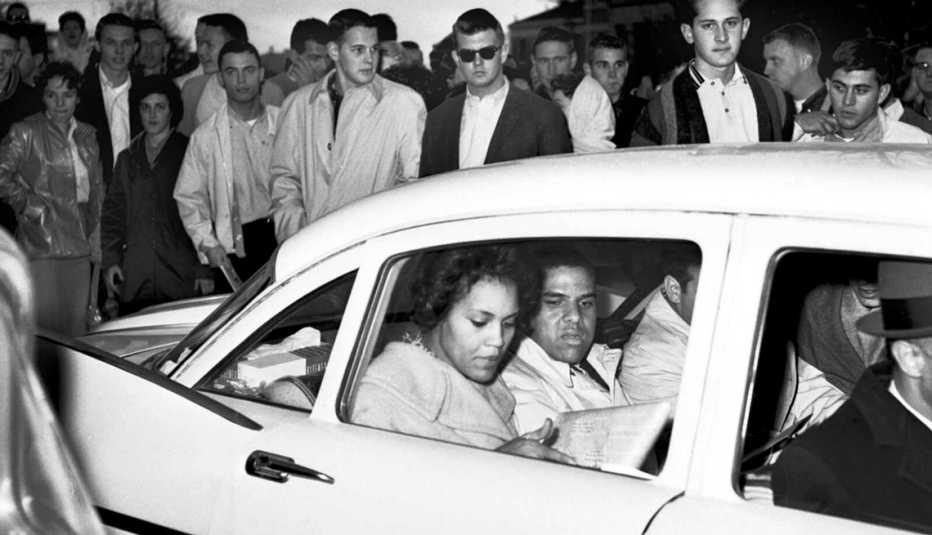

A crowd gathered in protest after she and classmate Hamilton Holmes (in car) registered to attend the all-white school

Corbis

Month after month I watched as my friends exposed themselves to palpable hate — and, sometimes, violence — but I refused to harbor anger. I knew that, like me, these students were wrapped in that familiar coat of armor and were simply doing what we were brought up to do: take control of our destiny — without ambivalence or fury or fear.

Upon graduation, I left for New York, where the late, great editor of the New Yorker magazine, William Shawn, had read about my case and my dream and invited me to join the staff, along with other young graduates from prestigious northern universities. Initially, like them, my job was typing rejection slips and story lineups, but before long I was promoted to reporter, the first black to be named to that position. I kept my eye on and my soul in what was going on in the civil rights movement, and wrote about black people in ways they were rarely portrayed anywhere in the media — in their full humanity. I continued this work at the New York Times, and in the decades since, never strayed, even as my reach widened to television, radio and other media, and to the world beyond our borders — most notably South Africa during the days of apartheid. I always felt I had a responsibility to confront issues of race and racism, but in ways that narrow the divide and focus on the positives of difference, rather than the all-too-exploited negatives. It hasn't been without its challenges. Once, when I was working at PBS' NewsHour, I surprised a white guest when he saw me sit down on the set to interview him.

"How long have you been doing this?" he asked after the show was over. And when I answered, "About 30 years," he responded, "Well, I guess it beats being a hairdresser."

I view unintentionally hurtful comments like that as coming from people who, if not ignorant, are uninformed. Unfortunately, expressions of racial insensitivity or hatred are still littering the landscape of our ever-elusive "more perfect union." And the reversal of some of the progress we made — sadly evident in the resegregation of our nation's schools and neighborhoods — is spurring scant public outrage, not even another righteous crusade. And so, wearing my invisible tiara, I continue to renew the commitment and the mantra of the civil rights movement: to "keep on keeping on," to use the values the village instilled in me all those years ago, to recite and write about our history and its relevance to our struggles today, to work at ensuring people are judged not by the color of their skin or the god they worship or the person they love, but by the content of their character — Martin Luther King Jr.'s dream of "the Beloved Community."

Charlayne Hunter-Gault is an award-winning journalist who has written about the civil rights movement in her books In My Place and To the Mountaintop: My Journey Through the Civil Rights Movement.

More on politics-society

The 50th Anniversary of the 1964 Civil Rights Act

The history and impact of the landmark law