AARP Hearing Center

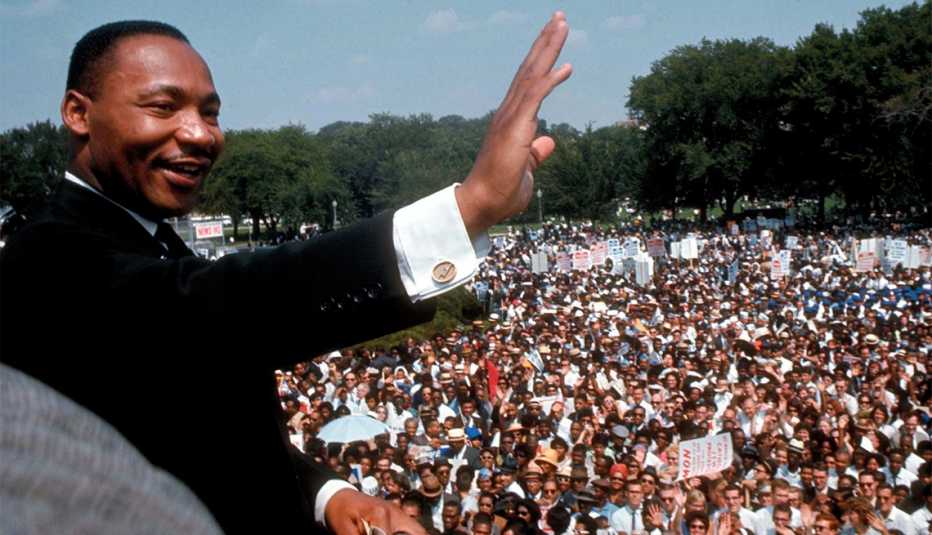

A personal relationship between Martin Luther King Jr. and President Lyndon Johnson became the cornerstone of a wave of civil rights legislation, including the Civil Rights Act, the Fair Housing Act, and the Voting Rights Act — the latter passed six decades ago this year.

These laws were among the harvest of King’s labor during the time that he led the nation’s civil rights movement, from the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955 until his assassination in 1968.

While the legislation King fought for improved rights for marginalized groups, legal rulings and weaker protections have, in recent years, chipped away at the gains.

Had King survived to a natural old age, he would be celebrating his 96th birthday on Jan. 15, 2025. Though he lived but a brief 39 years, he scattered the seeds of his quest for justice far and wide. Those ideals continue to inspire today’s leaders. Here are a few of them:

Stacey Abrams, 51

Historically, the path to voting for African Americans was obstructed by literacy tests, poll taxes and intimidation until the original Voting Rights Act cleared the way. But as many of those gains were being eroded in recent years, Stacey Adams stepped up. The former Georgia State representative built voter-protection teams, founded the Atlanta-based nonprofit advocacy group Fair Fight, and promoteed fair elections nationwide.

While her own campaigns to become governor of Georgia were unsuccessful, her impact on voting is undeniable. The Rev. Al Sharpton has said of the elections of Sens. Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock — and even that of President Joe Biden — “you’re looking at the work of Stacey Abrams.”

During 2024, she spoke to students around the country, imploring them to “do something, somewhere, soon,” and as Howard University’s first Ronald W. Walters Endowed Chair for Race and Black Politics, she hosted an election-focused speaker series.

The Rev. William Barber II, 61

William Barber was 4 years old when King visited the Mississippi Delta and saw a teacher divide up an apple to feed eight children. The hunger and misery the leader witnessed inspired the Poor People’s March on Washington: a caravan of more than a dozen covered wagons with slogans such as “Feed the Poor” painted on the side. The procession traveled from Marks, Mississippi, to the nation’s capital for a six-week protest. Barber, who followed in King’s footsteps as a pastor, has continued to carry on similar work across the decades.

He casts a wide net in his pursuit of justice. He went to North Carolina’s capitol to address the corrosive impact of partisan politics; he stood with “brothers and sisters from the Apache Stronghold” at the Supreme Court; and he traveled to Springfield, Ohio, to combat lies about local immigrants.

Bryan Stevenson, 65

At the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, lawyer Bryan Stevenson and his team have won reversals, relief or release for more than 140 wrongly condemned death row prisoners.

In a recent interview heralding the 10th anniversary edition of his bestselling memoir, Just Mercy, Stevenson highlighted a growing momentum against the death penalty. Nearly two weeks later, President Biden commuted the sentences of 37 of the 40 men on federal death row to life without parole.

The Equal Justice Initiative also focuses on quality of life: It launched an anti-poverty initiative in 2022 to address the hunger crisis in Alabama. The project also includes a health clinic that serves formerly incarcerated individuals and those without access to health care.

Dorceta Taylor, 67

“In King’s day, we fought to drink from the same fountain. Today we fight to drink the same quality water,” says Dorceta Taylor, who was named the Wangari Maathai professor of environmental justice at Yale University’s School for the Environment in 2024. The late Maathai founded Kenya’s Green Belt Movement, which has planted over 50 million trees.

Taylor is editor of the forthcoming Environmental Justice Encyclopedia and notes that King often spoke out against pollution, overcrowding and the need for parks — issues that today would be considered a call for environmental justice. Even the Montgomery Bus Boycott ties in: It ushered in a year of carpooling, she says.

Her work as a professor at Yale includes mentoring the next generation of environmentalists, which she calls “the most exciting part of my career.”

Lateefah Simon, 47

Early on in her career as the head of San Francisco’s Center for Young Women’s Development (now the Young Women’s Freedom Center), Lateefah Simon’s star rose for her work in aiding formerly incarcerated women, as well as girls who battled drug addiction, prostitution and abuse. Like King, who drew national attention at 26 for the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Simon was also a fledgling 26-year-old when she won the prestigious MacArthur “genius” grant.

An enduring racial and civil rights advocate in the Bay Area, today Simon’s string of successes include being elected to Congress, representing California’s 12 congressional district; leading change through grant-making organizations like the Meadow Fund and the Akonadi Foundation; and launching the Second Chance Legal Services Clinic, protecting communities of color, and low-income persons, immigrants and refugees.

Simon, who is legally blind, said in a KQED interview that “the beauty of this democracy is we get to stand up for one another.”

Janai Nelson, 53

In 1954, the year before King earned a Ph.D. from Boston University, the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund (LDF) won the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case in the Supreme Court. (The NAACP and the LDF became separate entities in 1957.)

In 2024, LDF President and Director Counsel Janai S. Nelson, raised a toast to a gathering of more than 650 people who came out to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the historic decision. The ruling not only began the work of desegregating U.S. schools, but also served as a gateway to the civil rights movement that King went on to lead.

Nelson continues to fight against unequal, segregated, and underfunded schools; battle mass incarceration; and demand an end to police brutality. The next front: bias in artificial intelligence.