AARP Hearing Center

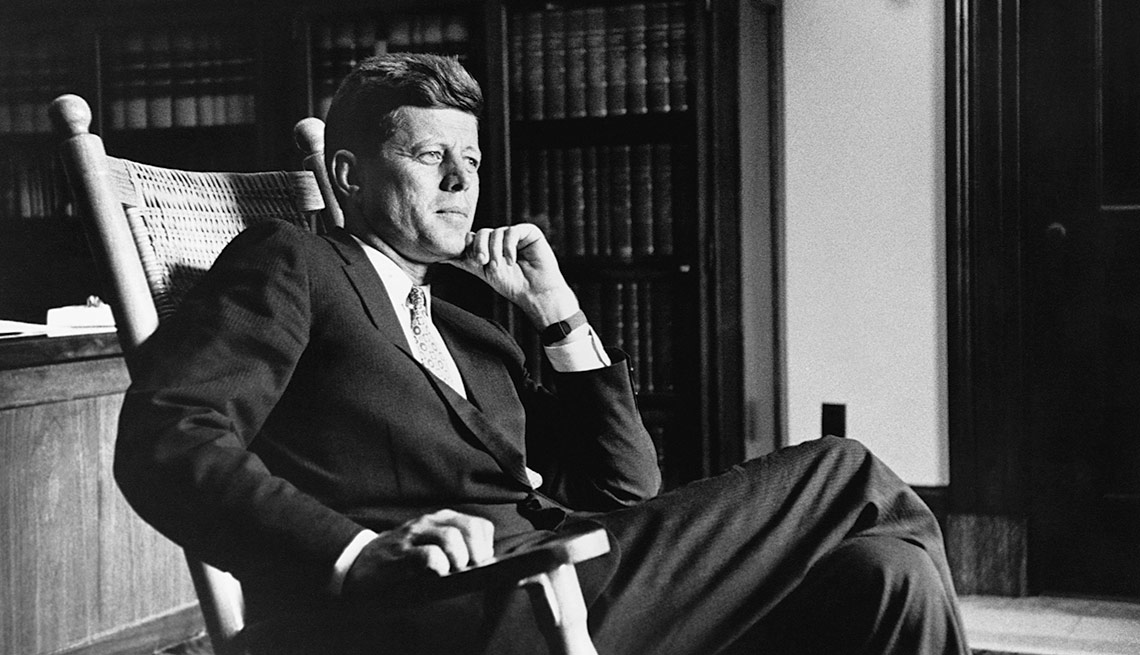

John F. Kennedy remains by far the most popular modern president, with an impressive 90 percent public approval rating, compared with the next two, Ronald Reagan at 69 percent and Barack Obama at 63 percent.

To be sure, his charisma, courage and early death (at age 46) largely drive that affection. Kennedy, after all, brought good looks and an easy aristocratic charm to the White House, exuding the panache of a Hollywood star in service of his political ambition. His chic Francophile wife, Jacqueline, reinvented the role of first lady, enhancing his appeal to women. The impossibly photogenic war hero president launched our epic journey to the moon and literally staved off a nuclear holocaust when he resolved the Cuban missile crisis.

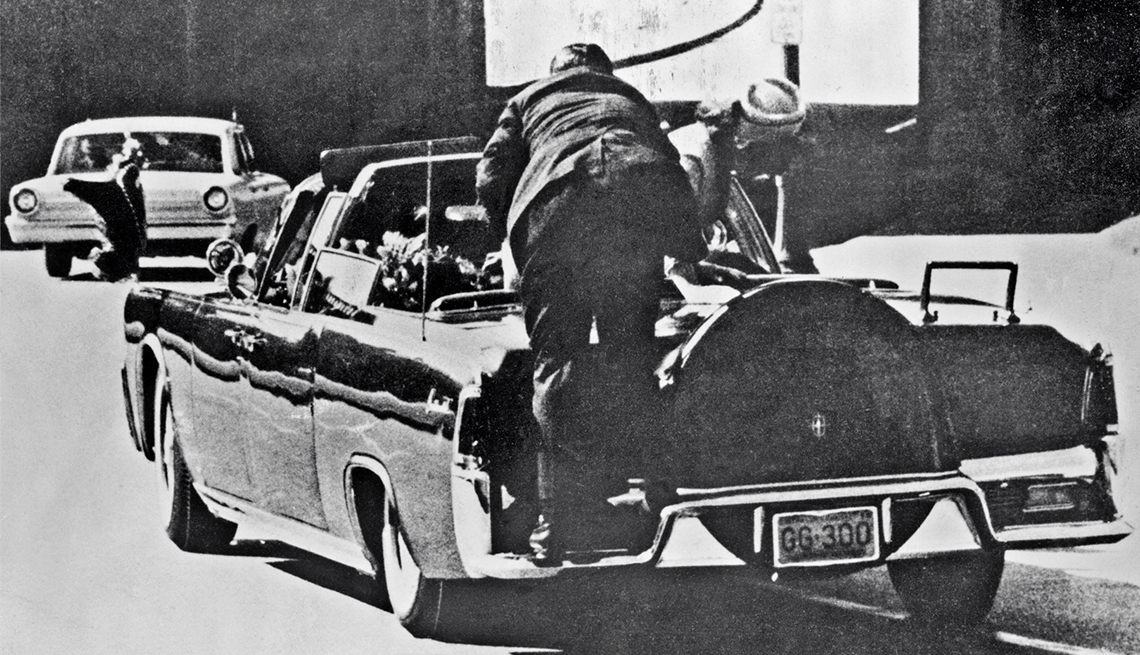

People still love JFK for the memory of the loss of all that, a leader cut down in his prime, Camelot destroyed, images of his murder and the aftermath — Jackie’s dignity in her blood-spattered pink suit, a funeral like no other in modern times — forever seared in our minds.

And, yes, the memory of JFK injects a dose of nostalgia for a time when the president stood slightly above the fray of daily life and was not another familiar face immersed in the 24/7 internet news cycle and its addictive spectacle of politics and polycrisis. Time does make the heart grow fonder.

But in the fullness of time, charm without compassion will not endure as long as charisma with principle. Kennedy deployed his eloquence for positive purposes. I posit that there are two broader reasons why people the world over still revere Kennedy, both of which crystallized on consecutive summer days in Washington 60 years ago, namely peace — and justice.

“What kind of peace do I mean?” Kennedy asked on June 10, 1963, in a commencement address to the graduating students of American University. “What kind of peace do we seek? Not a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war.”

Mere words, of course, but JFK (with help from speechwriter Ted Sorensen) voiced an aspiration that has never been more urgent. “Not the peace of the grave or the security of the slave,” Kennedy went on. “I am talking about genuine peace, the kind of peace that makes life on Earth worth living, the kind that enables men and nations to grow and to hope and to build a better life for their children – not merely peace for Americans but peace for all men and women– not merely peace in our time but peace for all time.”

More From AARP

Election 1960: JFK on the Campaign Trail

At age 43, John F. Kennedy became the youngest elected president, the only Catholic and the first born in the 20th century

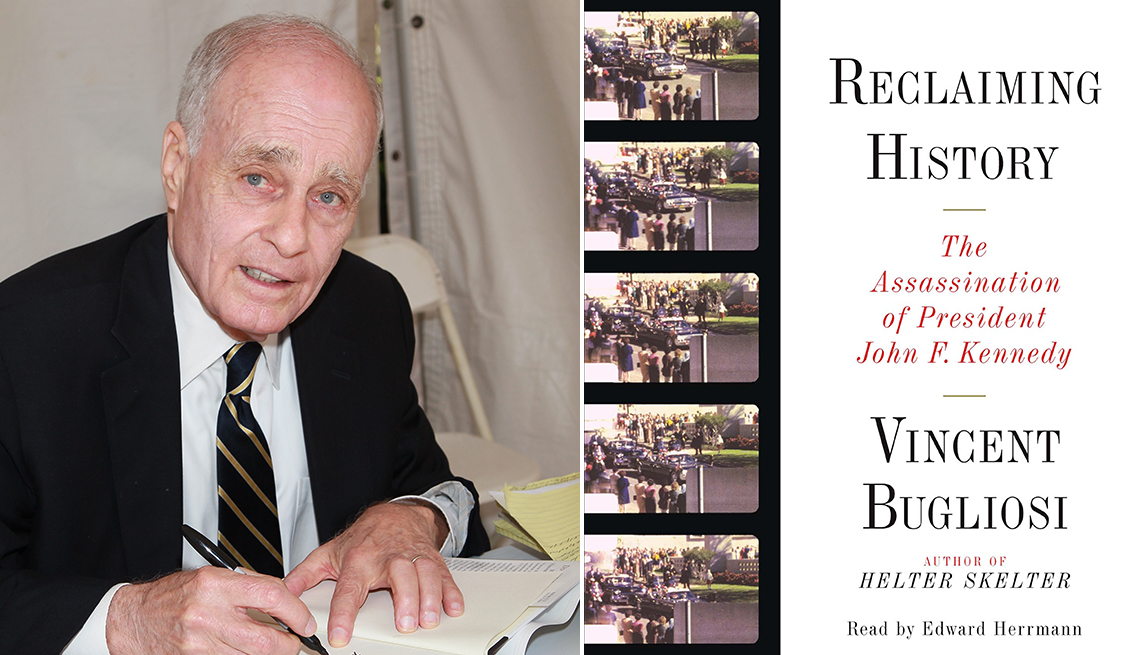

6 Myths About JFK’s Death

Famed Charles Manson prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi tackled myths about the assassination in his 2007 bookThe Kennedy Family Trivia Quiz

How much do you know about the Kennedys? Test your knowledge