AARP Hearing Center

Chapter 27

Wednesday, June 1, 2016

GRIZ AND I ARE BACK at Pearse Street by seven a.m., ready to go. As soon as I see her, I know there’s been a development.

“We got the ID,” she tells me first thing. “The remains are Katerina Greiner’s. Dentals confirm it.”

“Good,” I say. “What’s the story?”

“It’s an odd one. After they reported her missing, the brother ran into a friend of Katerina’s and the friend said he’d seen her in Berlin. They called off the search in Ireland. But the brother told me that he now questions whether that was true. The guy was also into drugs, he said, and he thinks maybe he was mistaken, or lying for some other reason. The family had sort of broken up at that point. The mother had died. The father had moved to Luxembourg, and it had been so long the brother just assumed that either she didn’t want to be found or that something had happened to her. After more years went by, he assumed it was the latter. There were the drugs, and she’d had a couple of suicide attempts, too. When the father died, the brother needed to have her declared dead so he could inherit the estate outright, so he went to court and got the paperwork completed. They must have done some sort of investigation but it didn’t turn up anything. It had been the right number of years.”

“Did she spend time in Dublin?” I asked Griz. “How did she and Erin meet each other?”

“The brother thought she must have spent a night or two in Dublin when she got here, but he doesn’t think she’d lived here.”

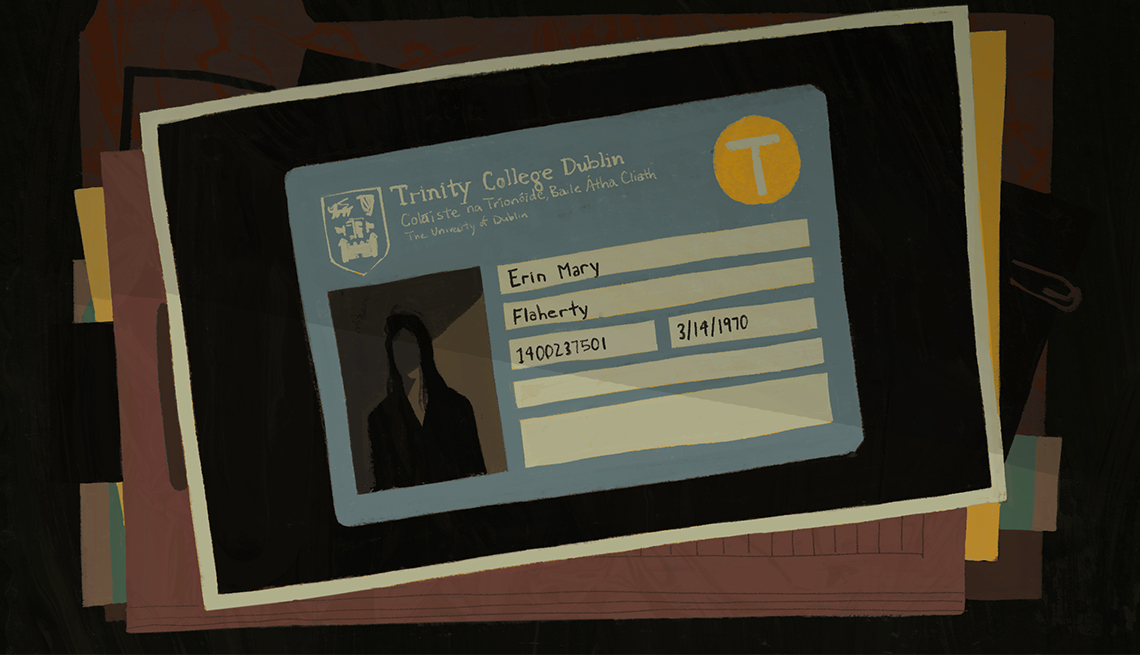

“So, why the ID card? Did she steal it? Did Erin give it to her?” I ask.

Griz knows what I’m thinking. Was Erin there when she was killed?

“We need more on her,” Griz says. “Joey’s going to go down and organize the door-to-doors. Roly said for me to keep at it here.”

I know what she’s saying. We have today and tomorrow morning. This is it.

“I guess we’d better get to it,” I tell her. I’ve brought my files and I put them on the table in front of Griz. “Take a look at all of this. It’s the stuff from Erin’s room at the Ringsend house. I’ve had it in my basement and I’ve looked at it a thousand times, but I was thinking about Katerina Greiner and, I don’t know, whether there’s something in there I didn’t know to look for before? Also, can you take a look at the missing persons lists so I can review them? I want to finish reading these files and then I’ll take a look at what your profilers have put together over the years.”

“Sure.” She takes the files from me.

“Thanks, Griz.”

We get to work. It’s a bright day, the sun angling in the conference room windows, and for the next few hours, everything narrows to the words in front of me and what they might mean.

***

I put June Talbot’s file and Erin’s file on the table in front of me.

June Talbot’s is fairly thin. They had been completely focused on the boyfriend for the first couple of days. Once they realized he had an alibi, they seemed to lose their momentum. Without a body, they hadn’t connected the disappearance to Teresa’s yet. There were a few interviews with possible eyewitnesses and men with records in Baltinglass, but by the time they’d realized that June’s disappearance might be related to Erin’s and Teresa’s, they’d lost some advantage.

Griz looks up. “I’ve got something else on Robert Herricks. An interview that wasn’t filed with all the rest. One of the girls who worked as a cleaner at the golf course with Teresa McKenny thought he was a little creepy. Something about him spying on them in the bathroom.”

“Anything else on him? Any harassment or sexual assault charges unrelated to Teresa?”

“I’m waiting on that. I’ll let you know as soon as I get it.”

I think for a minute. “Can you check in the system for any mention, not just charges?”

She wiggles her eyebrows. “They’re transitioning the database over or some shite like that. I’ll try.”

I turn to Erin.

It’s all here, a record of those two months of my life. The initial interview that Emer and Daisy and I gave at the Irishtown Garda Station, the interviews with neighbors and the other workers at the café.

The first thing I notice is how much of it there is. They were working it all along. What felt like inaction was just withholding of information. As soon as the report was made, the Gardaí in Wicklow had started canvassing, interviewing bus drivers, checking all the bed-and- breakfasts in Glendalough and Glenmalure. They’d discovered Mrs. Curran almost immediately.

The first interview with Conor Kearney took place the same day I reported Erin missing. They seemed to be looking at him fairly seriously — a couple of subsequent interviews with him, interviews with his known associates — until they interviewed Bláithín Arpin and she told them that he’d been with her at her parents’ holiday house in someplace called Brittas Bay the weekend of the sixteenth. Additionally, every single friend of his said he had never shown any signs of violence or aggression, that he was one of the kindest people they knew. A friend from his graduate program said he knew that Bláithín hadn’t liked Conor’s friendship with Erin, but that he didn’t think there was anything more in it than Conor feeling protective of Erin. “I always thought it was more a little sister sort of relationship than anything,” he’d told Roly and Bernie. “He seemed to worry about her.”

Back then, no one had told me Conor had a solid alibi for that weekend, and it makes sense all of a sudden that they turned away from him, especially once they knew Erin had gone back to Dublin. They’d clearly started looking elsewhere.

The other surprising thing to me is how seriously they seemed to be considering Gary Curran as a suspect. As they’d mentioned, he’d been cautioned for stalking a fellow UCD student a few years before Erin’s disappearance. The picture I get, though, is of a socially inept teenager with a desperate crush on a girl who became increasingly alarmed by his behavior. In their interview with him, he said he hadn’t met Erin because he’d been doing errands in Wicklow when she arrived at the bed-and-breakfast and then was off to work again by the time she left the next morning.

“Did you all look at Gary Curran again as part of the review?” I ask Griz.

“Yeah, but he’s been out of the country for most of the last twenty years,” she says. “It seems like they were looking at him for Erin initially, but not once their focus shifted back to Dublin, and he wasn’t really in the picture for any of the other disappearances. That’s my sense of it, like.”

Still, he and his mother were perhaps nearly the last people to see Erin, and they’re right there in Glenmalure. If I were in charge, I’d want to talk to him again.

After I told them about Hacky O’Hanrahan, they had gone and interviewed him at his parents’ house. The report lists the house name and address: Bridgehampton, Killiney Hill Road, Killiney.

The parents seem to have controlled the interview fairly tightly but Hacky O’Hanrahan had told Roly and Bernie the same things he’d told me, that he and Erin had met at a club and gone back to his flat in Merrion Square. She’d left in the morning and he’d never seen her again. That must have been before they started recording interviews, because instead of a transcript it’s a signed statement.

She seemed like a girl who wanted to have a good time. She was a nice girl. But she was the one who said she wanted to come home with me. She seemed pretty happy, if you want to know the truth. She said to ring her so I did. But she didn’t ring back and I left it. I didn’t even think of her again until I saw the thing on the SixOne.

Reading between the lines, I can tell that they thought he was an asshole. But there isn’t anything more incriminating than that.

I turn to Niall Deasey.

Roly and Bernie had gotten the Murphy brothers’ names from the Westbury and run them through the system. I remember the conference room, Wilcox’s gaze on me as I said I’d never heard their names. He’d probably thought I was in on whatever it was Erin had been involved with. I read the detectives’ statements, laying out an incomplete profile of the brothers.

They had been born in 1940 and 1945, respectively, and after a middle-class Irish American childhood with four other siblings in Somerville, Massachusetts, they’d started a cement company that had been very successful, mostly by obtaining contracts with the city of Boston and other municipalities in the suburbs. The Murphys had been active in raising money for IAFNI, the Northern Ireland aid organization I’d learned about from Ingrid, in the ’80s and early ’90s, and there was a note that the US Department of Justice knew about them because of it. Whatever they were up to then, they’re both dead now, one from lymphoma and the other from a classic widowmaker heart attack while eating at a Boston steakhouse.

It still isn’t clear, though, exactly why they were flagged in the system.

And it leaves unanswered another question: Who was the guy from the North?

On to Niall Deasey. It’s all the stuff Bernie and Roly told me. He owned a local auto garage in Arklow and, the Arklow cop told them, he probably dealt drugs and, in his younger years, did a little armed robbery here and there. His father, Petey Deasey, had been a known republican but Niall Deasey, in the ’80s and ’90s, was known to have associations in criminal enterprises in Wicklow and Dublin that had connections to dissident republican groups claiming to be fighting the drugs trade. But after 1998, he seemed to fall off the radar a bit, and at some point there was a note that he’d moved to London to run a garage with his half-brother. He seemed to have stayed out of trouble since then, and in 2013, when his mother became ill, he moved back to Arklow and reopened the garage. Back in 1993, a local cop had a chat with him and asked him about the Americans. He claimed that the American men were over as part of some conference for breeders of boxers. He’d corresponded with them before the conference and taken them out for pints when they’d arrived. It didn’t seem like anyone had believed that story, though.

That’s it. I Google Drumkee and read some more Irish Times stories about arms dumps in Wicklow and Carlow and about Kevin Whelan and the graves of other victims of the loyalist and republican paramilitary organizations. There’s something knocking around in my head, something about Katerina Greiner and Erin and what they were doing in the forest in Wicklow, but I can’t find it: It’s like a marble that keeps rolling just out of reach.

Griz is still working the missing persons cases, to see if she can identify any other possible victims. Now that we know he buried Katerina Greiner, it opens up the possibility that there are undiscovered victims.

She shows me a huge stack of sheets printed from the database: missing men and women of all ages. Before 1990 the names are mostly Irish ones, but starting around 2000 there are Polish and Bulgarian names and then, more recently, Chinese and Nigerian ones.

“A lot of these probably went home, but it’s a lot,” Griz says. “What I wanted to ask you, though, is if you have any ideas about Brenda Donaghy. I’ve started looking a bit but I can’t find any evidence she returned to Ireland. I talked to all the Donaghys in Dublin, which is a lot, but no one’s missing a daughter of the right age.”

“I’ve done as much nosing around as I could over the years,” I tell her. “After she left my uncle, she didn’t leave any tracks. I checked Social Security, DMV, marriage and death certificates. I couldn’t find anything. A few years after Erin went missing, my uncle had to admit to me that they’d never actually gotten married, so I wondered if she had a different name. He told me that she loved shrimp — she always ordered it when they went out to dinner—and that she used to tell him about going to the beach in somewhere called Sherries or Serries. My instinct is that Erin never found her, but obviously I can’t be sure.”

“Skerries. It’s a beach town north of the city. I’d say that’s what it was. I was wondering if maybe there was someone connected to Brenda Donaghy,” Griz says. “A brother or a friend or ... I don’t know. Maybe it was when Erin went looking for her mother that she met the fella who ... who killed her or who she’s with. Maybe he’s the same guy who killed Katerina Greiner. Maybe he’s our suspect for the others, too. I don’t know. We know who the rest of our suspects are. Like you said, maybe there’s someone here who we don’t know about yet.”

“It’s a good theory, Griz.” I can feel my pulse speed up a little. She’s right. If Erin made contact with Brenda or with her family in Ireland, then there’s a whole pool of known associates we haven’t identified yet.

“All right,” she says. “I’m going to put together something we can post up near Skerries. It’s worth a try, sure. Here’s the other thing you asked for — as part of the last review, we checked homicides and missing persons files in the Republic and up north, looking for patterns. There were a couple of disappearances near Newry that were being looked at as part of a pattern around 2006, but two of the women turned up years later and one was killed by her husband. He’d taken the body to a friend’s garage and they buried it at a junkyard.”

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members