AARP Hearing Center

Chapter 29

1993

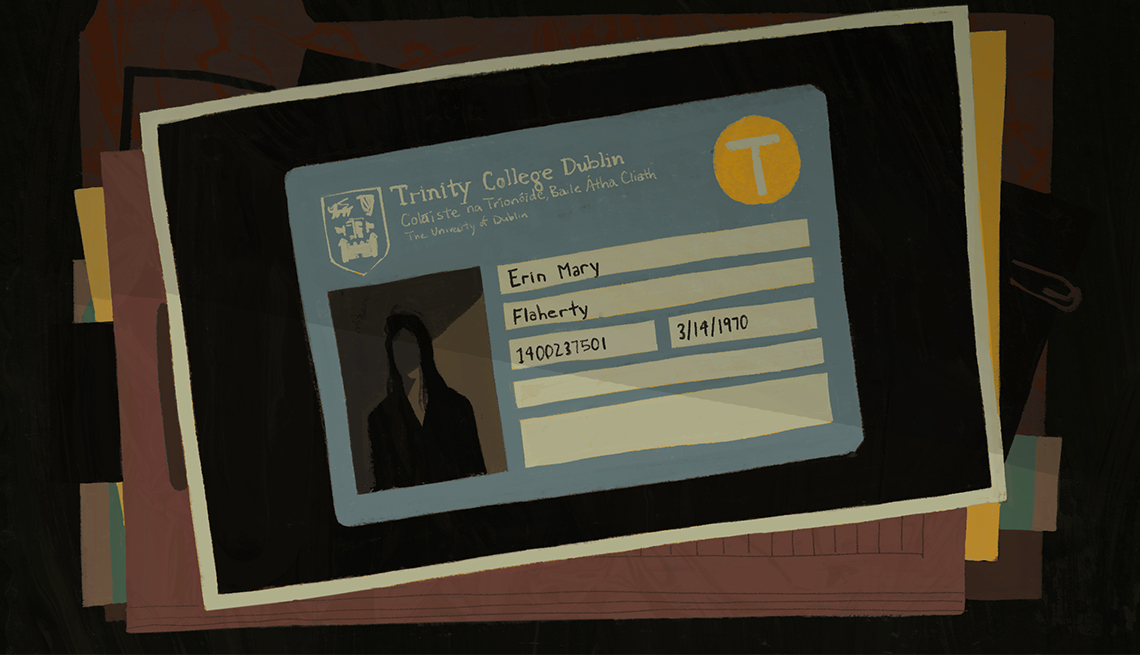

THE MORNING AFTER I was followed, I woke up to a note by the phone in Emer’s writing: Erin’s da rang. Talked to Detective Byrne. Ring him when you can. When I went out to the corner shop for eggs and coffee, I picked up an Irish Times as well, and I was sitting at the table in the kitchen, eating scrambled eggs, when I read the small headline on an inside page: “Gardaí Say No Indication of Foul Play in Erin Flaherty Case: Active Search Suspended.”

The Gardaí say they have moved on from the initial stage of their investigation into the disappearance of American student Erin Flaherty and will suspend active searches. Detective Superintendent Ruarí Wilcox says that the working theory is that Flaherty is traveling and hasn’t been in touch with family and friends, and that there’s no evidence of foul play. Nonetheless, the Gardaí have been unable to definitively rule out an abduction in the Wicklow Mountains. Wilcox says that any members of the public with information about Miss Flaherty should call the Gardaí Helpline on 1-3045672.

The receptionist at the Irishtown Garda Station saw me coming and stood up as though she was going to physically prevent me from getting through.

“I need to talk to Detective Byrne and Detective McNeely,” I said. “I know they’re here.” The look on her face told me I’d gambled right. “I’ll just check now,” she said. “I believe they may be in a meeting, however.”

“I’ll wait,” I said. I sat down and picked up an Irish Independent. It had a longer version of the same story, with a quote from a criminologist at Queen’s University Belfast saying that, with no evidence of foul play, the case does seem to be that of a “young woman who has decided to disappear of her own accord.”

It was Roly who came down to talk to me, sheepishly opening the door and coming to sit next to me in one of the hard plastic chairs.

“You called my uncle and told him you’re stopping the investigation.” He was staring straight ahead, not looking at me. “Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Now, we’re not stopping the investigation, D’arcy. We’re — One phase has been suspended, pending further developments, now, and then we’ll see where we are. We’ve thoroughly investigated every lead there is, and if new ones emerge we’ll investigate those, too, but —”

“What about Niall Deasey? Have you thoroughly investigated him?” I said, too loudly. Roly winced. “And why didn’t you tell me? I’ve just been waiting for someone to call me back, like an idiot. What about her mother?” My head was pounding and my stomach actually hurt. I felt like I was going to throw up.

“D’arcy, you’ve been a bit erratic. There’s a feeling that you’re too involved. Now, I know that may be my fault, but for the good of the investigation, we need you to be patient and wait a little. Maybe you could go home for a bit and then check back with us when—”

“Erratic? You think I’m being erratic? Do you know what happened to me last night? Some guy followed me. He was there all the way home and when I got back to the house, he waited for me. I went and got a screwdriver because I thought if he tried to attack me I could —”

“D’arcy, please tell me you didn’t fight with some fella on the street.”

“No, but I waited and sure enough he followed me. I asked him if he knew anything about Erin and I swear he did. He had this look in his eyes.”

Roly ran a hand through his hair and said, “D’arcy, you’re making this very difficult for me. If there really was someone following you, you’d no right to confront him. It’s mad. He might have been a mentaller and he might have attacked you.”

“He might know something about Erin. I wrote down a description.”

“D’arcy.” He leaned in, his voice very low. He glanced up at the receptionist and said, “My job is on the line here. I’ve been told to keep you away from the investigation. I need you to stay away.”

“But—”

“I’m sorry, D’arcy. I’ll be in touch if there’s anything new.”

He stood up and started to walk away, but before he opened the door, he turned around again. His eyes were shadowed and I could see the strain on his face. He looked years older than the Roly Byrne I had met when I reported Erin missing. He said, “I really am sorry, D’arcy,” and then he was gone.

***

I went for a long run, nearly six miles, and took a hot shower in the empty flat when I was back. I had that light, anxious, hollowed-out feeling you have when you’ve just recovered from a hangover. I knew I should drink lots of water and have a quiet night in.

Instead I went to the Raven. The red-headed barman was behind the bar, and I sat on a stool and chatted with him while I drank cider and got the update on his girlfriend and told him about Uncle Danny and the bar.

A couple of older guys joined us and we all shot the shit for a while, until I was good and tipsy and the sun was gone and the streets of Temple Bar were full of people. I walked for a bit, feeling the hard elbow of my loneliness in my side. And then I took a right onto Eustace Street.

He was there, locking up, and when he saw me, he didn’t say a word. He just put the keys in his pocket. It was a dark night and his face was in shadow. I stood in front of him on the empty street. I was suddenly sober, the chilled wind coming off the river a jolt of adrenaline.

“Let’s walk,” he whispered.

We started walking, along the quays, and we didn’t touch until we were past the DART station. On City Quay, he took my hand. The sky was dark gray above the river. We could see our breath on the air.

Once we got to Gordon Street, I let us in and we stood for a minute in Erin’s silent room, staring at each other in the low light coming in the window, breathing, before he reached for me.

For years, I would remember almost everything about that night, the way the light came through onto the bed, the way his lips brushed my shoulders, the blur of his face above me, the feel of the corded muscles along his back, and the way he smelled — sweat and smoke and the cold metal tang of the outside air still on his cheeks and hands.

We talked in hushed voices all through the dark night, murmuring into each other’s bodies, skin on skin, lying tangled under the sheet. I memorized the shape of his neck, his shoulders, his stomach.

He said, “I can feel your heart beating.”

I put his wrist to my lips and said, “I can feel your pulse.”

“Why are you crying?”

“I don’t know.”

When the sky began to lighten, I asked him, “What’s the worst thing you’ve ever done?”

He was silent for a long time. Finally he said, “I can’t.”

I traced the line of his jaw with my index finger.

I said, “One time, when I was ten, I had to go looking for Erin. My uncle woke up and she was gone and he called us. My mom went door to door and she told me to go down and check the beach. Erin loved the beach. I walked for a long time and then I saw her. She was sitting on a log and when I got to her, she didn’t even look up, she just said, ‘Leave me alone. I don’t want to go back.’ I told her everyone was worried about her and she didn’t say anything. She was stacking these rocks on the log and she kept stacking them, making little piles. I didn’t know what to do. I just sat there. Finally she got up and started walking. I just followed behind her, until we got home.”

He stroked my hair away from my temples.

“Did you ever ask her? Did you ever ask her why?”

“She would never say. I always thought it was ... my fault somehow. Because I had a mother and she didn’t. Because ... I just thought it was my fault.”

“You can’t think that,” he said. “Where do you think she is?” His body was warm against my cheek.

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members