AARP Hearing Center

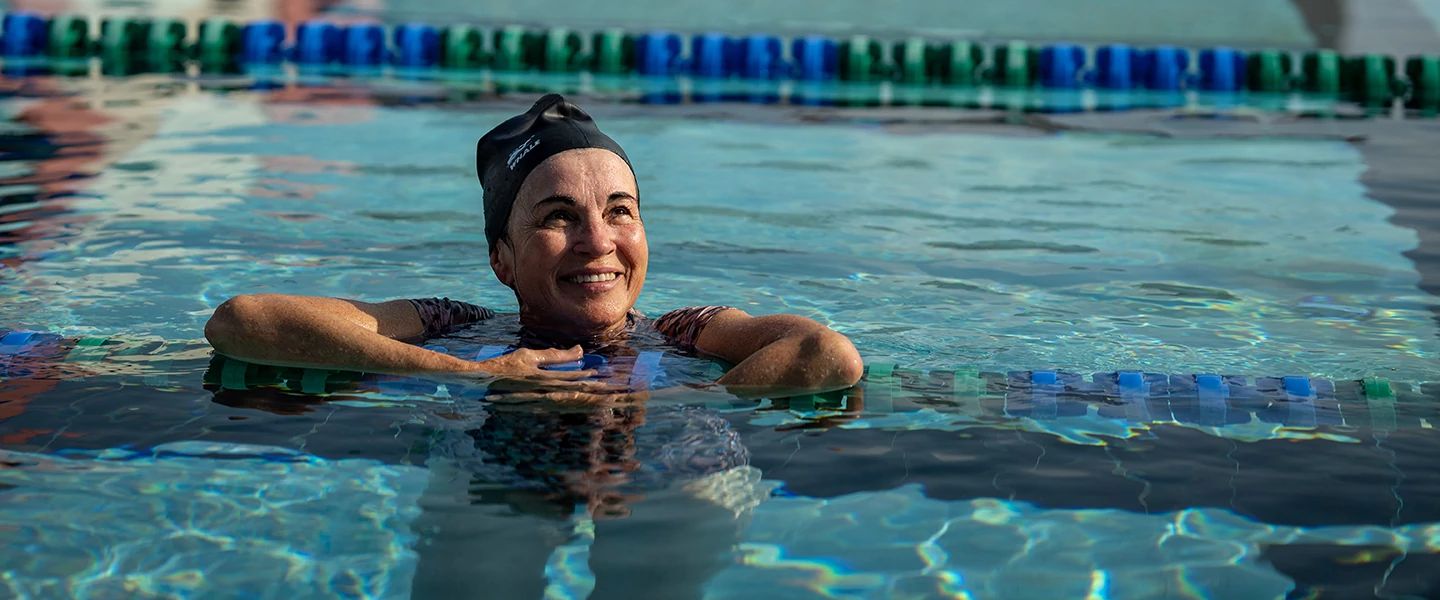

Maria Rodriguez, 67, approached the Venice, Florida, YMCA pool deck, then backed away.

As with so many other people, earlier traumatic experiences stood in her way, preventing her from learning to swim despite its numerous benefits.

Rodriguez grew up around water on Pico Island, Portugal, but never learned to swim. Though she often went with her brothers to the ocean, there were no beaches where she lived. The land was rocky, the water was deep, and currents could be strong, so she’d use an old tire as a floatation device when she ventured in.

“They didn’t know I didn’t know how to swim or breathe in the water and how fearful I was,” says Rodriguez, now a grandmother of four grandchildren, ranging from 2 to 8 years old.

Affable yet soft-spoken, Rodriguez describes herself as “nervous, humble and shy.” Those traits were barriers that she had to break through to learn the basics of swimming, after which she started to gain the confidence she had lost four decades ago.

A terrifying plunge

In her mid-20s, Rodriguez was at a poolside celebration while visiting a brother in Canada when a partygoer playfully pulled at the towel she was resting on, causing her to topple down to the bottom of the pool. Someone jumped in to rescue her, but after that, she was always afraid of water.

It wasn’t until her mid-30s that Rodriguez was able to approach the water again, with the encouragement of her second husband, Hector, but she went in only up to her knees. Rodriguez would take her two sons — now ages 40 and 43 — to the beach and to pools to ensure that they were comfortable in the water.

The argument for learning to swim is compelling: Nearly 2,000 people age 50 and older died from unintentional drowning in the United States in 2022, says Tessa Clemens, a health scientist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of Injury Prevention. That number accounts for nearly half of the 4,000 annual drowning deaths, according to a recent report from the CDC. Drowning death rates among those over 65 have been increasing for decades, with 15 percent of U.S. adults age 45 to 64 reporting that they don’t know how to swim. For adults 65 and older, that figure is 19 percent.

The deaths disproportionately affect some age, racial and ethnic groups. Rates are consistently highest among males, Black Americans and Native American peoples or Alaska Natives. Some 55 percent of U.S. adults age 45 to 64 have never taken a swimming lesson; 57 percent of those 65 and older have never done so. Although Rodriquez’s brothers learned to swim, no one in her family had lessons.

Water, water everywhere

After immigrating to the United States in 1979, Rodriguez met her husband. They settled in Middleton, Rhode Island, where she already lived with two children from a previous marriage. Although she couldn’t swim herself, she got her children into swimming lessons at early ages, and they became competitive swimmers.

Rodriguez devoted her adult life to supporting other family members: as a parent of two sons who became extensively active in their education and after-school activities as an involved grandparent, and assisting her husband in the success of his financial planning business.

A snowbird, she toggles between living in Venice and Aquidneck Island, Rhode Island — both communities geographically embraced by water.

Although she was often around water with her family, she made sure she was never at the beach or pool with her grandchildren without her husband or sons, who are “awesome swimmers,” she says. She didn’t talk to them about not being able to swim.

“To me, that was something that was painful inside my heart, but the fear and the anxiety of the water overcame the other part of me that wanted to learn,” she says

Taking the plunge

Watching a video of her youngest granddaughter getting ready to start swim lessons prompted Rodriguez to face her fear and seek out lessons of her own.

She drove to the YMCA in Venice, parked and then drove away. Finally, she gathered the courage to go back, walk through the door and ask to see the athletic director about swimming lessons.

You Might Also Like

Find the Road Trip to Match Your Inner Map

Are you a foodie or history buff? Whatever your personality, we have the perfect journey for you

Canine Companions Provide Vital Caregiving Assistance

Four-legged helpers can assist with daily tasks and even monitor medical conditions

What We Can Learn From the Japanese About Finding Purpose

‘Ikigai’ means making your life worthwhile — here is how you can implement it

Recommended for You