AARP Hearing Center

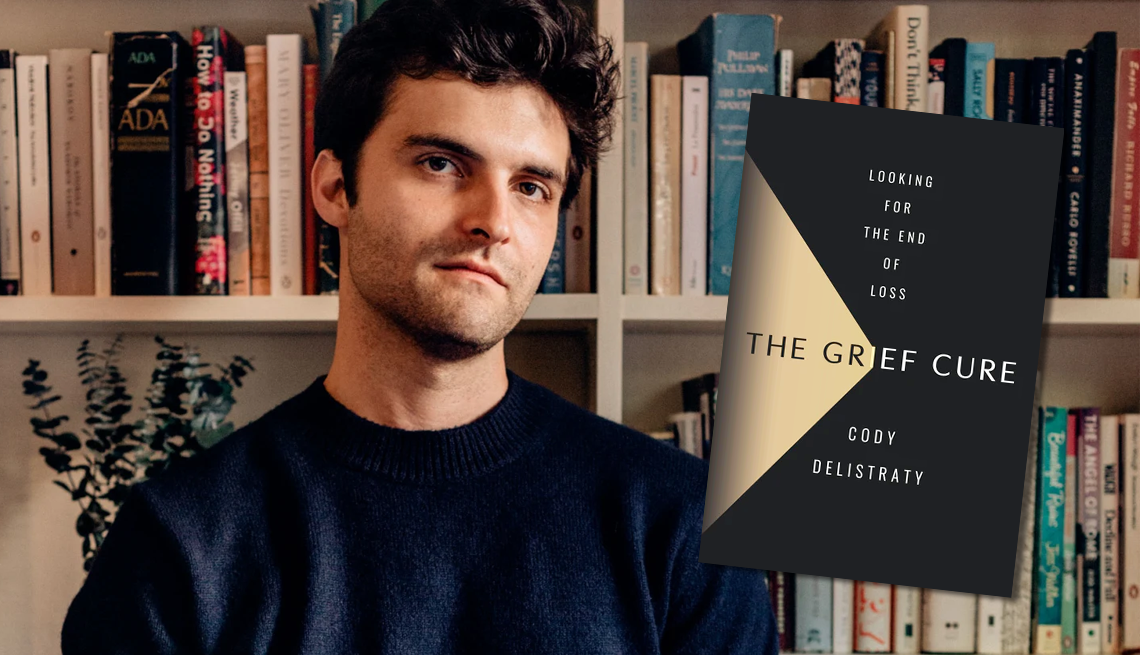

Like many of us, Cody Delistraty knows the heart-wrenching devastation of losing someone you love. When he was 21, his mother, Jema Delistraty, died from melanoma.

During her illness, Delistraty thought, If I can be really good in my studies, really good at athletics, just really good at something, then I could somehow save my mom. And after she died, he expanded that pressure on himself, thinking, I have to be a good griever now.

“What that meant to me, through the received wisdom of growing up in the U.S., was to keep it quiet and work hard to get to this construct of closure,” he says. “That didn’t work.”

Amid his struggles to find some peace, Delistraty, a journalist, speechwriter and former culture editor for The Wall Street Journal, embarked on a deep dive investigation into grief. He examined historical and cultural attitudes and sought insights from technologists and therapists, among other experts. He also explored traditional and unconventional methods to potentially ease the pain, which ranged from talk therapy to messaging with AI-created bots that reflected his mom’s interests and communication style.

Now, 10 years after his mother’s death, he recounts his experiences and what he learned in The Grief Cure: Looking for the End of Loss. Delistraty discusses the insights he gleaned while researching the book and throughout his emotional journey.

Q: You covered a lot of ground in your research. Can you share some of your overarching observations?

A: One relates to public grief. We have shifted from a very public grief to a more private, repressed grief. However, we’re seeing a slight shift back now, with a kind of hybrid grieving. People are putting their grief online and finding places to talk about it outside the formality of a therapist’s office, such as online meetup groups where there’s a shared buy-in of “we’re all here to discuss the harder aspects of being human. We’re all here to discuss the loss.”

The falseness of closure was something that also struck me. It’s ultimately a mythical idea. You’re not going to get total closure or reach a state of complete acceptance. Yet, across American culture, we have this deep implication that grief is something you can really blow past. There’s no federal law for bereavement leave. The median is five days off for the death of a close family member. It’s one day off for the death of a close friend. When my mom died, we hadn’t rearranged the bedroom in five days, let alone my dad being ready to go back to work or me [being] ready to go back and finish up college.

More From AARP

A Caregiving Son’s Enduring Grief

Losing my father at a young age changed the course of my life and careerWhoopi Goldberg on Grief: ‘It Doesn't Go Away. It Just Kind of Evolves’

Award-winning actress and ‘The View’ cohost pens candid memoir honoring her late mother and brotherHow to Handle ‘Hard Feelings’ After Caregiving Ends

Guilt and withdrawal can make the grieving process even more difficult