AARP Hearing Center

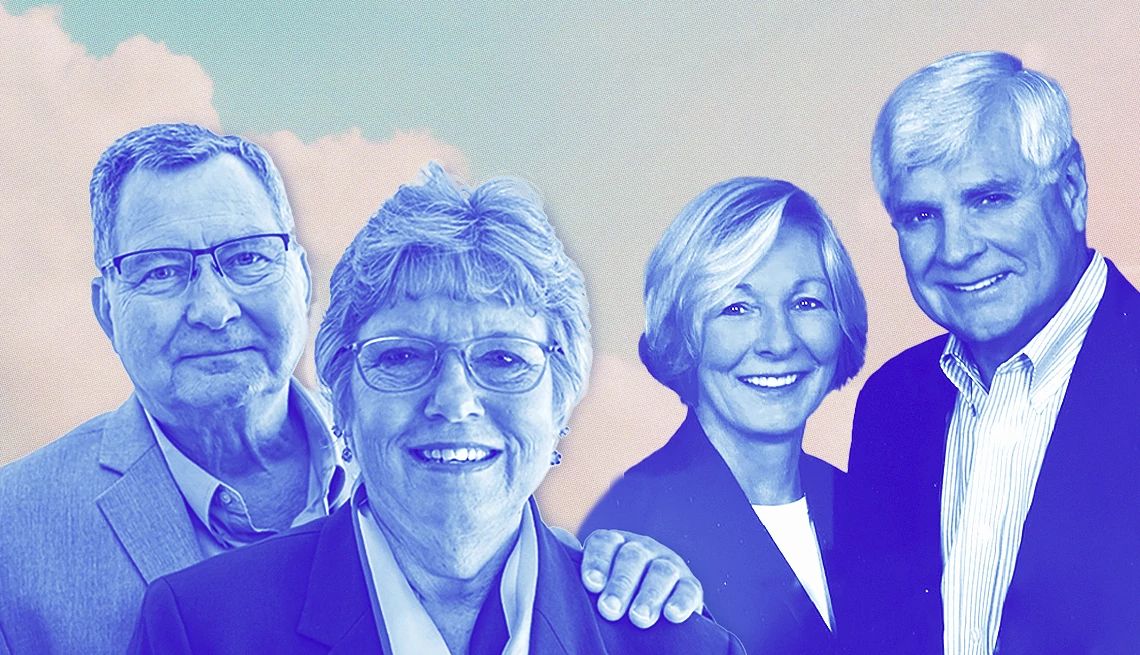

Marty Parrish, 61, was 17 when he had his first bout of major depression. The Johnston, Iowa, resident was in his 50s when he found a treatment that works, long term, for him.

It was his wife, Peggy Huppert, 65, who got him out the door, day after day, for those treatments, he says. Huppert says she’s done that many times in their 15-year marriage, through multiple bouts of depression and rounds of treatment. “There are times when I literally drag him out,” she says.

But Parrish says he doesn’t see it that way: “She's always been there for me … it’s not that she drags or pulls me, she just holds my hand.” And that has made all the difference, he says: “If it hadn’t been for Peggy, I wouldn’t be alive today.”

Across the United States, millions of caregivers are figuratively or literally holding the hands of older adults with depression. In some cases, they’re helping someone with a first bout, triggered by illness, personal loss or isolation. Others have loved ones like Parrish, who’ve struggled with depression for decades.

Here’s what you should know and what you can do to help if you suspect or know that someone you care about has depression.

Recognize the signs

Depression is more than a passing blue mood. It’s a medical condition that negatively affects how people feel, think, act and see the world, according to the American Psychiatric Association. Contrary to popular belief, it’s generally more common in younger people than in older people, the association says.

Depression “is not a normal part of aging,” says Erin E. Emery-Tiburcio, a professor of geriatric and rehabilitation psychology at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago.

Still, depression affects about 15 percent of adults over age 65, according to the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. Older adults are especially likely to be depressed if they are in hospitals or nursing homes, or if they have other illnesses, such as cancer, Parkinson’s disease, heart disease, stroke or Alzheimer’s disease, the association says.

Anyone who’s had depression before also is at higher risk for depression later in life, according to the National Institute on Aging.

If you think of depression as just sadness, you might miss it in many older adults. A loss of interest in previously enjoyable activities is a more common symptom, Emery-Tiburcio says. Someone “blankly watching TV all day” might be depressed, she says. So might someone sleeping more or less than usual. She adds that older men, in particular, may seem more irritable than sad.

Depression can be diagnosed when sadness, feelings of emptiness, loss of interest in activities or other key symptoms last at least two weeks and get in the way of everyday life, according to the psychiatric associations. Other symptoms can include:

- Feeling slowed down

- Frequent tearfulness

- Feeling worthless or helpless

- Suddenly losing or gaining weight

- Pacing and fidgeting

- Poor concentration

- Thoughts of death, or suicide attempts

While older adults are less likely to be depressed, they are more likely to die by suicide, with the highest rates in men over age 85, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (If you are worried about suicide risk, you can call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988, 24 hours a day.)

Reach out for help

If you think a loved one is depressed, “don’t ignore them, don’t walk away, don’t give them all their space,” Parrish urges. He knows from painful experience, he says, that the depressed person may “build this wall” to keep others away.

But, he says, “That’s when we need you to come sit beside us and just say, ‘Is everything OK?’ ”

When someone is clearly not OK, your goal should be to get them to a doctor for a physical and mental evaluation, says psychiatrist Ken Duckworth, M.D., chief medical officer of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and author of You Are Not Alone. Primary care doctors routinely handle such workups, he says.

More From AARP

25 Great Ways to Build Healthy Habits

These tips can help create changes that positively impact your well-being for years to comeHow to Be a Caregiver for Someone With Chronic Kidney Disease

Consistent medical monitoring and a healthy diet can make a big differenceHow to Be a Caregiver for Someone With COPD

Care for a COPD patient at home and improve their quality of life