AARP Hearing Center

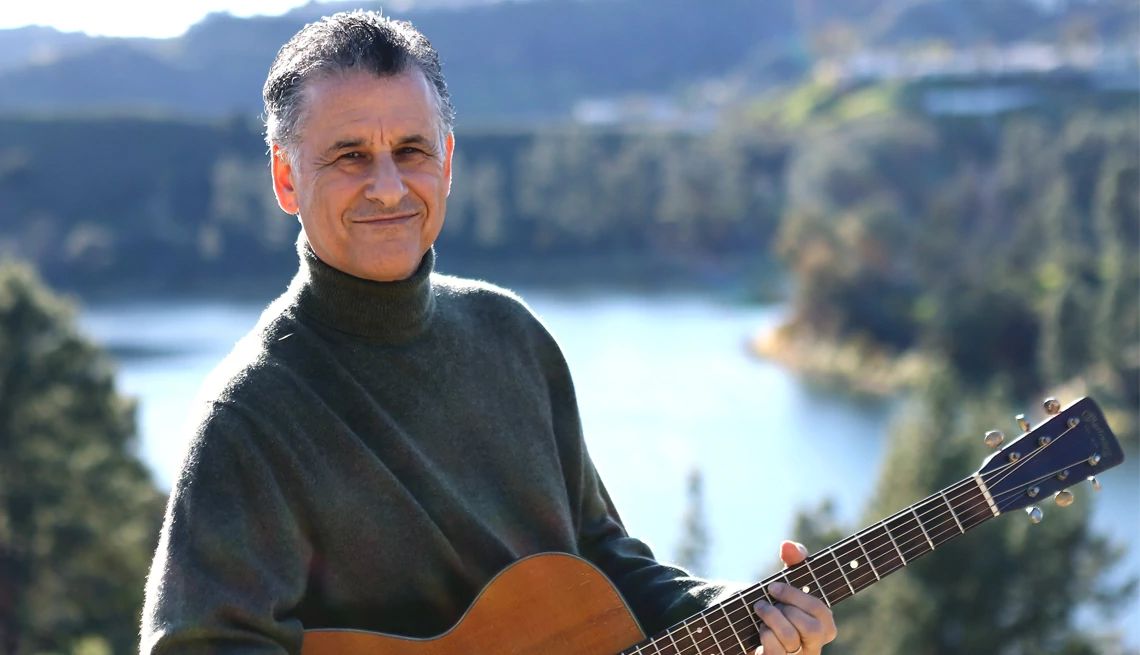

After publishing This Is Your Brain on Music in 2006, Daniel Levitin felt like he still had unfinished business. “I couldn’t write the book I wanted to write, because there wasn’t enough research,” he says. Today, science has finally caught up. In I Heard There Was a Secret Chord, the McGill University neuroscientist and musician explores how music can change modern medicine, from the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases to pain relief.

You explain in the book that music can be a better tool for sparking memories than, say, looking through a photo album. Why is that?

Some music we listen to is uniquely associated with a particular time and place. If you think back to the summer between seventh and eighth grade, there were probably songs that you were listening to a lot then, and they kind of mark that time for you. This is the key to why music is so powerful at treating Alzheimer’s disease and profound memory loss. The music of our youth gets stored with special clarity. That music can even relax and calm somebody with Alzheimer’s who can’t remember who or where they are and who doesn’t recognize their loved ones. It’s the one thing in their lives that’s familiar.

You explain that music is also a good way to relieve pain. How do doctors use it today, and how can that work be generalized?

My lab was the first to show that, when you listen to music you like, your brain produces opioids. Your brain isn’t producing these opioids at pharmaceutical levels, but it’s producing enough of them that you can probably [treat your pain] with, say, an aspirin instead of a Vicodin. Or, if a Vicodin, maybe half the dose and for half the time. So, you’re less likely to get addicted. Dentists have figured this out. Long before there were studies on it, if you were to get your teeth drilled, they might have you listen to music.

AARP’s Brain Health Resource Center

Find more on brain health plus dementia, stroke, falls, depression/anxiety and Parkinson’s disease.

Where is the evidence strongest that music is a form of medicine? And what are the illnesses it can treat?

One of the best cases is Alzheimer’s disease, in patients who might otherwise be agitated, violent or catatonic because they’re so disoriented. Music can bring them back. Another good case is Parkinson’s disease, which is characterized by the degradation of the neural circuits that allow you to move smoothly, particularly walking. If we play music that’s at the same tempo as the footsteps of someone with Parkinson’s, they can walk smoothly. The effects can last for six months after a course of rhythmic therapy. [Also known as rhythmic auditory stimulation, it is a form of movement therapy in which patients practice walking while listening to music matching their normal speed.]

That’s impressive. Do doctors use music often?

Some are, but not enough.

You’ve played music with and gotten to know many professional musicians. How has music impacted the health of your musician friends?

I think the obvious example is Bobby mcFerrin, who has Parkinson’s and who’s been able to continue performing. The performances actually help keep some of the Parkinson’s symptoms at bay. After Joni got home from the hospital [Joni Mitchell had an aneurysm in 2015], she couldn't walk or talk and was disengaged from much of the world around her. But she started listening to her favorite songs and they reconnected her with the self she had lost. They motivated her to begin the long, difficult and arduous recovery process. I have another friend, a country Americana folk artist and songwriting mentor named Rodney Crowell. He uses music to process the various traumas in his life. I think all artists to some degree are working out emotional stuff, whether it’s painting, sculpture, dance or literature.

More From AARP

How Does Music Boost Your Mood?

New report highlights link between music and mental well-beingMusic and Dance Help People with Parkinson's

People with Parkinson's harness the power of music to connect, move with others

AARP’s Brain Health Resource Center

Find tips, tools and explainers to support your brain

Recommended for You