AARP Hearing Center

It wasn't until Herb Jones III and Rodney Jones got older that they understood the impact of having a father who was a Tuskegee Airman.

"He never really talked about it in the context of the historical significance of the Tuskegee Airmen, which we found out about a lot later on in life,” said Rodney Jones. “When the Tuskegee Airmen finally started to receive a lot of long-overdue recognition and accolades from the country and the rest of the world."

The Tuskegee Airmen consisted of young Black men like Herb Jones Jr., born in 1923, who enlisted during World War II to become the country's first Black military pilots. They trained at Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama. Despite racism, segregation and doubts over their abilities, the Tuskegee Airmen went on to fly missions during the war. Their success ultimately contributed to the desegregation of the U.S. Armed Forces.

But rather than representing the pinnacle of his aviation career, being a Tuskegee Airman was just the beginning for Jones, who turned his passion for flying into a string of accomplishments over many decades.

"That's been a recurring theme throughout his lifetime as it relates to his Tuskegee Airmen experience, [which was] a springboard to almost 70-plus years of a wonderful aviation career,” Rodney Jones said.

One of their father's early mentors was Chief Alfred Anderson, the primary instructor at the Tuskegee Air Field. The pair originally met when Anderson gave Jones some of his first flight lessons in Arlington, Virginia, during his teenage years. Jones grew up in nearby Washington, D.C.

"My father was a protégé of Chief Anderson and remained friends with Chief Anderson throughout his 70-year career in aviation,” said Rodney Jones, “which he really attributed to his Tuskegee experience that led to other ventures, all in the field of aviation."

Career takes flight after WWII

Despite their military service and training in the U.S. Army Air Corps, a precursor to the U.S. Air Force, Tuskegee Airmen were denied the opportunity to become commercial pilots for major airlines upon returning home after the war.

"So rather than, you know, mope on that, my Dad moved to the next step,” said Jones III.

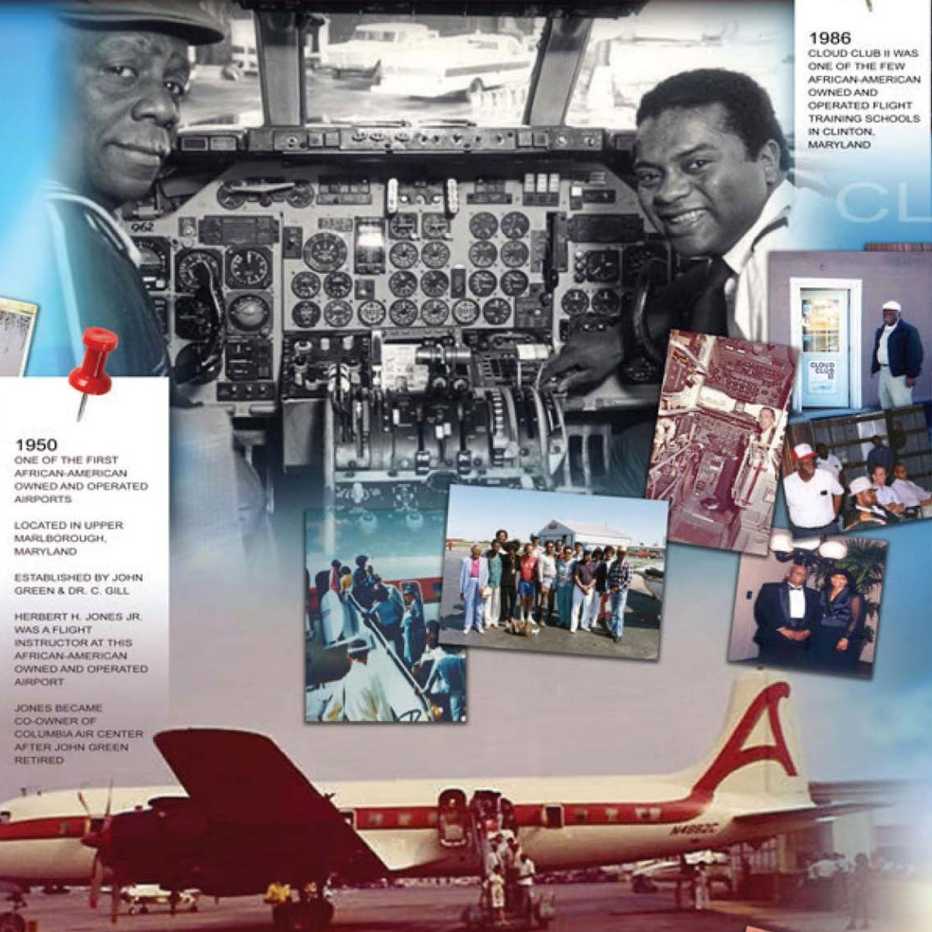

Jones Jr. spent three decades training aviation cadets at the Columbia Air Center while working for the Civil Air Patrol, from which he retired with the rank of lieutenant colonel. He eventually became a co-owner of the Columbia Air Center, the first Black-owned and operated airfield in Maryland.

Retirement from the Civil Air Patrol didn't leave him grounded. In 1972, Jones and four others purchased a 100-passenger DC-7 aircraft and created the International Air Association, a Black-owned airline. It offered flights to New York, Houston, Miami, the Bahamas and Trinidad.

More on Home and Family

Tuskegee Airman Gets Wish to Help Dyslexic Students

Frank Macon overcame learning struggles to fix, fly planes for U.S. military9 Top Military Museums and Memorials

Explore fascinating sites across the nation, from Pearl Harbor to Gettysburg