AARP Hearing Center

During their weekly phone call in December 2016, Alison Hill sensed something was amiss with her mother, Valerie Hill. Normally reserved, the 93-year-old woman sounded giddy.

When she pressed her mother for details, the older woman revealed that soon none of her children would need to worry about money. They were going to be rich.

Alison asked her mother, who lived along Florida’s Gulf Coast, to tell her what was going on. “I can’t,” she replied. “It’s a secret.”

The exchange “sent up red flags,” said Alison, 67, an artist and gallery owner who lives in Maine.

She remembered that a couple of months earlier, her mother had mentioned she had received a notice in the mail announcing she had won a Publishers Clearing House sweepstakes. Initially, her mother dismissed the prospect of collecting her winnings, saying she didn’t want to appear on television.

After the call with her mother, Alison phoned her four sisters, saying they needed to figure out what was happening.

Early into the sisters’ sleuthing, a paper trail emerged and showed suspicious withdrawals from their mother’s bank account.

One sister who kept an eye on their mother’s account discovered that several checks for about $9,500 each had been written to another woman but assumed the largesse was related to their mother’s church. Valerie Hill was a daily churchgoer and active in her Catholic parish.

It wasn’t long before the account showed suspicious withdrawals to make wire transfers to Jamaica and buy money orders.

All five sisters urged their mother to reveal what was going on, but she was tight-lipped. They implored her not to give away more money. “She agreed, but only to keep us quiet,” Alison said.

Her sister Abbe Hill, 55, a scenic artist from Brooklyn, said her strategy was “to ask a lot of questions and give her information about being careful and watching out for scams.”

“That wasn’t working,” she added. “The money was still going” out.

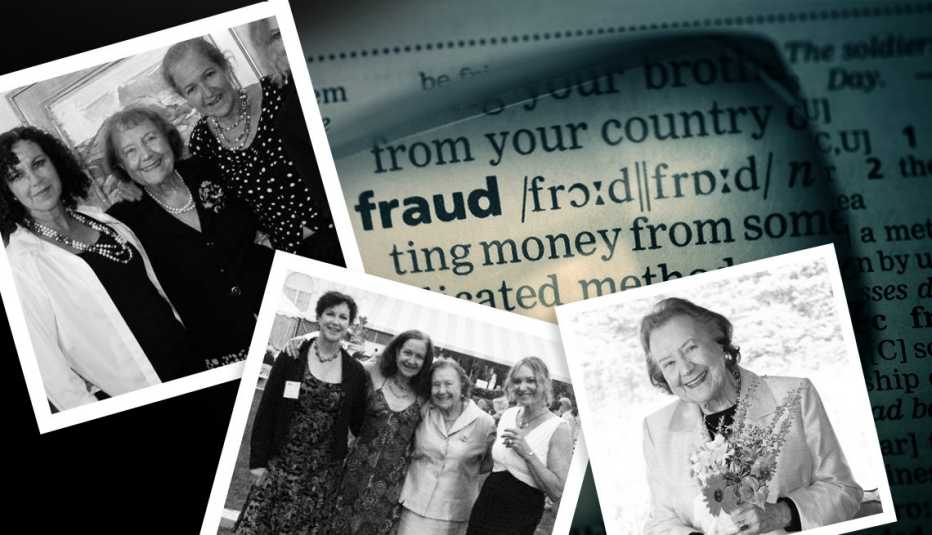

Alison, Abbe and their sister Melanie Preston, 63, are sharing their story because they want to protect older Americans from falling victim to scams like their mother did. A once-vibrant retiree who in the years after World War II flew international routes as a flight attendant for American Airlines, Valerie Hill was widowed at 39. After losing her husband, she bought and sold real estate to put their six children through college.

Her behavior throughout the scam “was extremely out of character,” Abbe said.

Swinging into detective mode

Valerie Hill’s five daughters and a son live outside Florida. The sisters decided to team up and visit their mother to get to the bottom of her runaway spending. Two sisters flew down in February 2017 and were alarmed to learn their mother had looked into refinancing her condo. “She never took out loans for anything,” Alison said.

When Alison and sister Abbe traveled south a month later, they uncovered an accordion file containing more troubling clues: Papers showed their mother was trying to obtain additional credit cards and open other bank accounts. Another telling document: Alison and Abbe found what appeared to be a Publishers Clearing House notification that “looked official, except when you examined it closely,” Alison recalled.

While talking to Abbe, Valerie Hill disclosed that a man had come to her condo with a briefcase full of prizes and promised they would be hers once she completed a process.

One scammer from the purported sweepstakes even told their mother on the phone to imagine how it would feel when she was driving her new Mercedes, according to Melanie, a jewelry maker who lives in Newport, R.I.

Their mother “was a really rational person, so we didn’t understand how they got her acting this way,” according to Abbe, who said the older woman even told the scammers not to call when her daughters were visiting.

Listen to Valerie's story on The Perfect Scam

Scammers Drained the Life out of Our Mother: Part 1

Valerie receives a letter stating she's won the Publishers Clearing house sweepstakes, but it's not what it seems.

Scammers Drained the Life out of Our Mother: Part 2

With the stress of a sweepstakes scam damaging Valerie's health, her daughters take drastic measures.