AARP Hearing Center

When it comes to being heard at the ballot box, America’s older voices have been getting louder for years.

And they continued to roar in this week’s election.

Numbers from AP VoteCast show that voters 50 and older made up 52 percent of the voting electorate. They went for former Republican President Donald Trump 52-47 percent over current Democratic Vice President Kamala Harris. So even though younger voters may have given the nod to Harris, the larger bloc of older voters had a bigger stamp on the outcome.

It’s a continuation of a trend underway for decades.

Indeed, the fact that older voters turn out in numbers well above other age groups is a truism in electoral politics — “almost like a law,” says Michael McDonald, a professor of political science at the University of Florida.

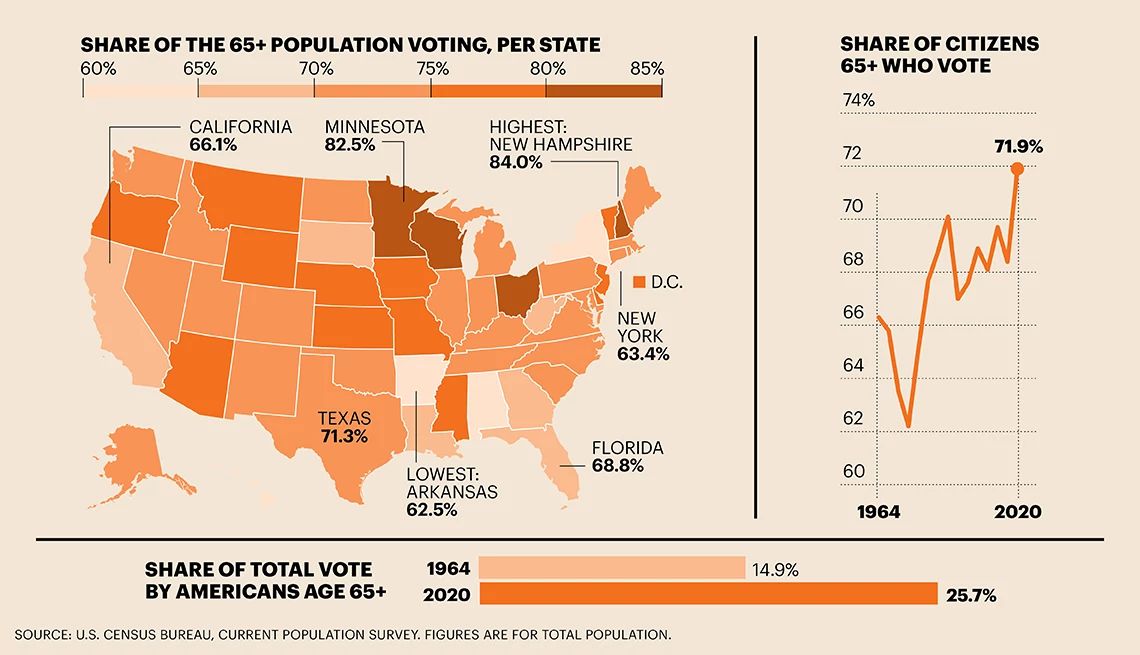

But it hasn’t always been that way: In decades past, younger cohorts voted at higher percentages than those 65 and older. It wasn’t until the 1980s and ’90s that turnout among people 65-plus eclipsed other age groups tracked by the U.S. Census Bureau. Since then, the gaps between older voters and younger ones have generally grown.

The reasons for the change are both simple — increasing voter-outreach efforts by groups focused on the needs of older Americans — and complex: a deeply felt sense of civic involvement among those who became active in the 1960s and ’70s. And over the years, voting has become easier, with mail ballots and expanded in-person options more prevalent.

What’s more, older people know voting matters — a lot.

“There are two issues that absolutely dominate the interests of our constituency: Medicare and Social Security,” says Nancy LeaMond, AARP executive vice president and chief advocacy and engagement officer. “It’s also very clear that elected officials have a big role to play in those programs.”

More From AARP

Older Voters Are Focused on the Economy This Election

This powerful voting group has pocketbook issues top of mindHow Voting Laws Will Impact 2024 Elections

Some states have tightened their rules since 2020, but others have made it easier to cast a ballotHow to Register and Vote in the 2024 Election

State-by-state guide to everything you need to knowRecommended for You