AARP Hearing Center

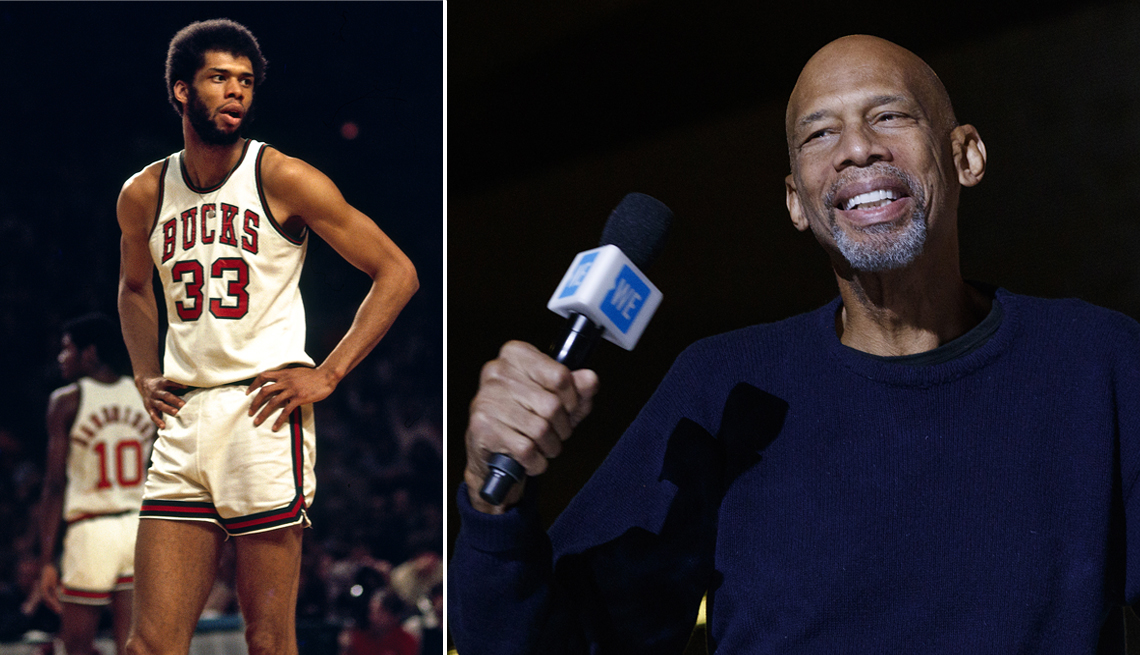

Editor's note: On Feb. 7, LeBron James, 38, of the Los Angeles Lakers, broke Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s nearly 39-year-old scoring record of 38,387 points. In the process, James became the NBA’s all-time leading scorer. He ended the game with a career record 38,390 points. Abdul-Jabbar, 75, was in the stands to witness his record fall. He congratulated James on the court and handed him the basketball.

In an interview with TNT after the game, Abdul-Jabbar was asked about any similarities between his own activism and the way James uses his voice off the court. “Oh yeah, listen. What LeBron has done off the court is more important than what he’s done on the court,” Abdul-Jabbar said in response, citing James opening a school and “providing leadership and an example of how to live.”

Abdul-Jabbar wrote an essay in May 2021 for AARP discussing his fight for racial equality. The full text appears below:

In 1675, Sir Isaac Newton explained his remarkable achievements in physics by saying, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” That expression of humility and gratitude resonated with me so much that I titled my book about the literary, political, musical and sports giants of the Harlem Renaissance On the Shoulders of Giants.

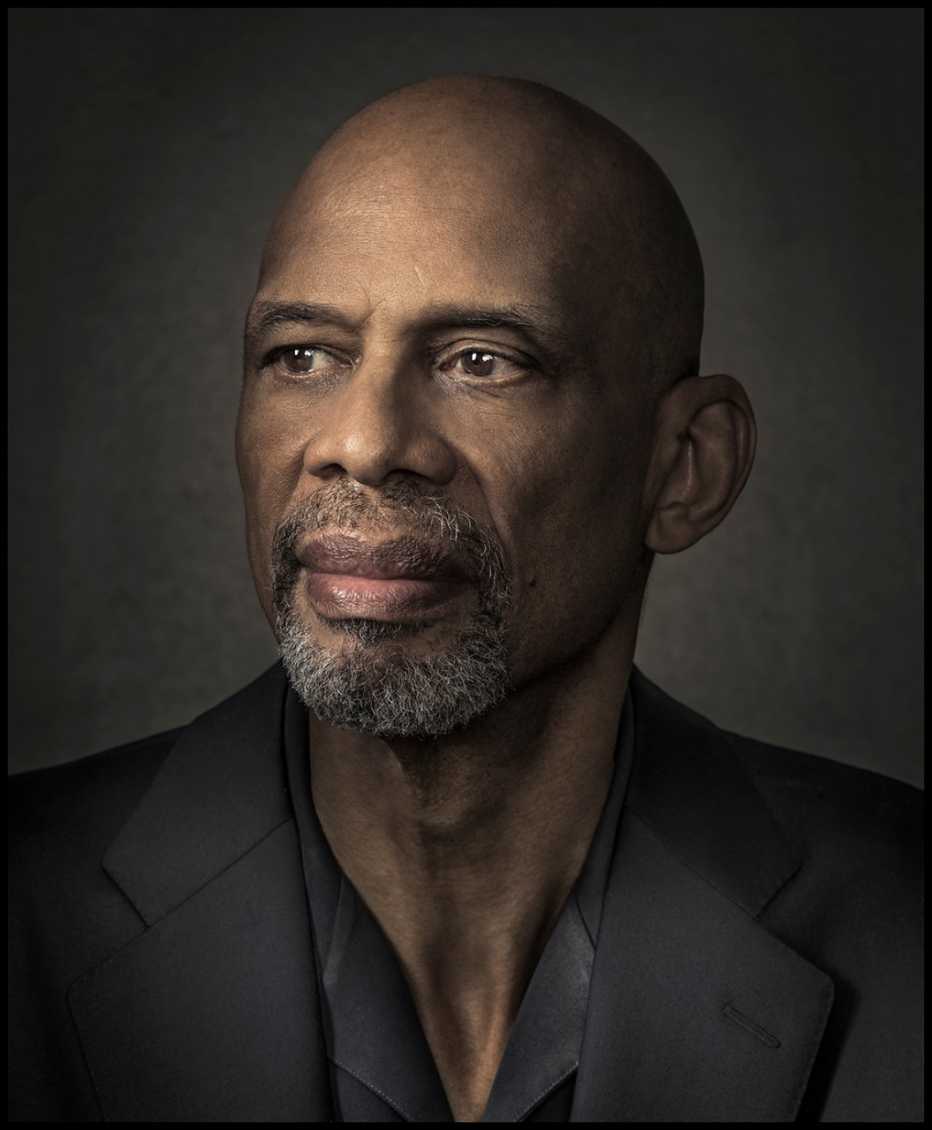

In the 32 years since I retired from the NBA, I have been writing books, articles, documentaries and movies about many of the overlooked giants of color throughout American history. No group has had more influence on society — and on me — than athletes. Because of the courageous men and women who played games for a living, I have not only seen further but been able to achieve more in a profession and a country that for so long routinely resisted people of color. And, sadly, still does.

Now it's almost time for the Olympics, and the best athletes in the world will gather to prove once again that human beings are capable of more than we thought possible. People will jump higher, run faster and leap farther than ever before. And the rest of us will watch in awe, fervently believing that the human body is an unstoppable vehicle of the imagination, rather than a thick tether of aging flesh. To watch Olympic athletes soar is to feel, if even for a few moments, untethered.

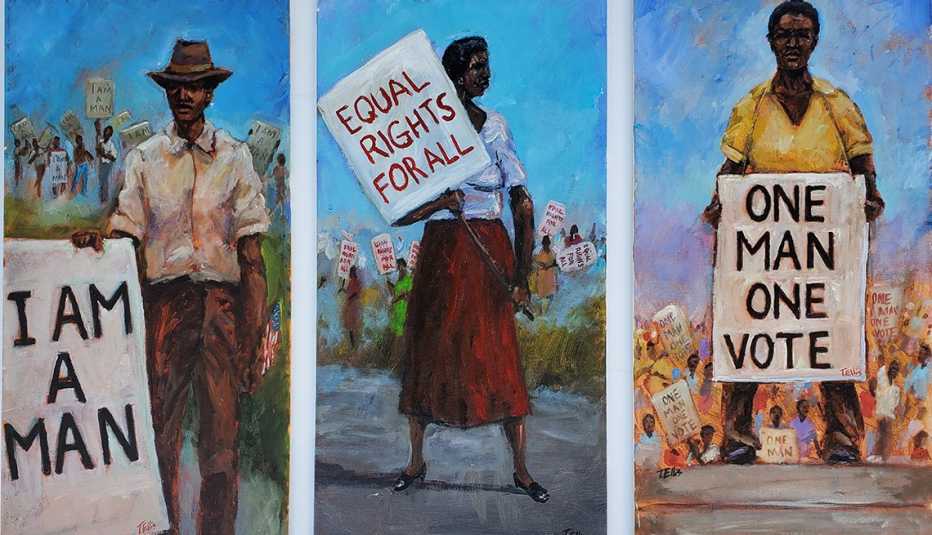

In 1968, I was asked to join the Olympic men's basketball team, but I refused, as a protest against the police violence and brutal racism bubbling up throughout the country. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated in April of that year, and there was an anger and hopelessness permeating the Black community. I didn't feel comfortable being an envoy of the American way to the rest of the world, as if everything was OK.

It was an act of defiance that probably hurt me more than it did the country, but after watching Muhammad Ali sacrifice his heavyweight-championship title, endure three years of being banned from boxing (worth millions of dollars) and face imprisonment simply because he was a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, I had to heed my conscience as well. I couldn't forget his story of coming home after winning an Olympic gold medal in boxing, only to be refused service at a restaurant in his hometown. He was one of the giants who hoisted me up.

For the past hundred years, sports has been both a litmus test and a spearhead for racial progress. In some cases, Black athletes trying to break through the color barriers were like canaries sent into a coal mine to choke on the poisonous racism. In other cases, they endured the foul air and kept getting up, each time proving their worth as athletes. Like many pioneers, they were attacked, abused, vilified, excluded, jailed and sometimes beaten or worse. For Black athletes, trying to break into white sports was like climbing a rope that stretched up into the clouds — while someone set the bottom on fire.

My own climb up that rope has not been without feeling the heat from below. But the greats who came before me were like thick knots in the rope, each helping us all climb just a little faster and just a little higher.

Paul Robeson, Jackie Robinson, Jim Brown, Muhammad Ali, Bill Russell and Arthur Ashe are only a few of the giants on whose shoulders I ascended. More important than how to be a winning athlete, they taught me how to be a significant athlete. They taught me that winning wasn't just about trophies and rings but about using those things as currency to lift up the rest of the community. They taught me that every time I spoke out about injustice, I was providing strong shoulders from which the next generation could climb higher.