AARP Hearing Center

If you feel like your sleep isn’t what it used to be, you’re probably right. Even healthy aging is associated with changes in sleep patterns like shorter sleep duration, less deep sleep and more frequent awakenings throughout the night.

But it’s not all bad. In fact, despite these typical shifts, healthy older adults tend to report fewer sleep problems than younger generations. Put another way, the older you are, the less likely you are to be bothered by an imperfect night’s sleep, says Michael Grandner, a clinical psychologist and director of the Sleep and Heath Research Program at the University of Arizona.

That could help explain why, despite a recent AARP survey showing that 70 percent of adults 40 and older reported having sleep difficulties, another study, published last month by Saatva, showed that only 20 percent of boomers said they always or often struggle to get up in the morning. That’s compared to 43 percent of millennials and 48 percent of Gen Zers — even though the older cohort didn’t report that their sleep was any more restful.

“Part of it might be resilience; part of it might be changing expectations; part of it might be perspective and ability to cope,” Grandner says.

But if you’re not coping well with sleep issues in your 50s, 60s and beyond, it could be a sign of a health condition that deserves medical attention — and treatment.

“The important thing to remember is if you’re getting older and you feel like your sleep is a problem, if it’s not really interfering with your ability to function, maybe that’s more the normal aging side,” Grandner says. “But if it is actually becoming a real problem, don’t let your doctor just say, ‘Eh, this is just part of aging.’ There might be a solution for this.”

Here are five conditions other than insomnia that may be leading to poor sleep — and how better sleep can help fend off disease in the first place.

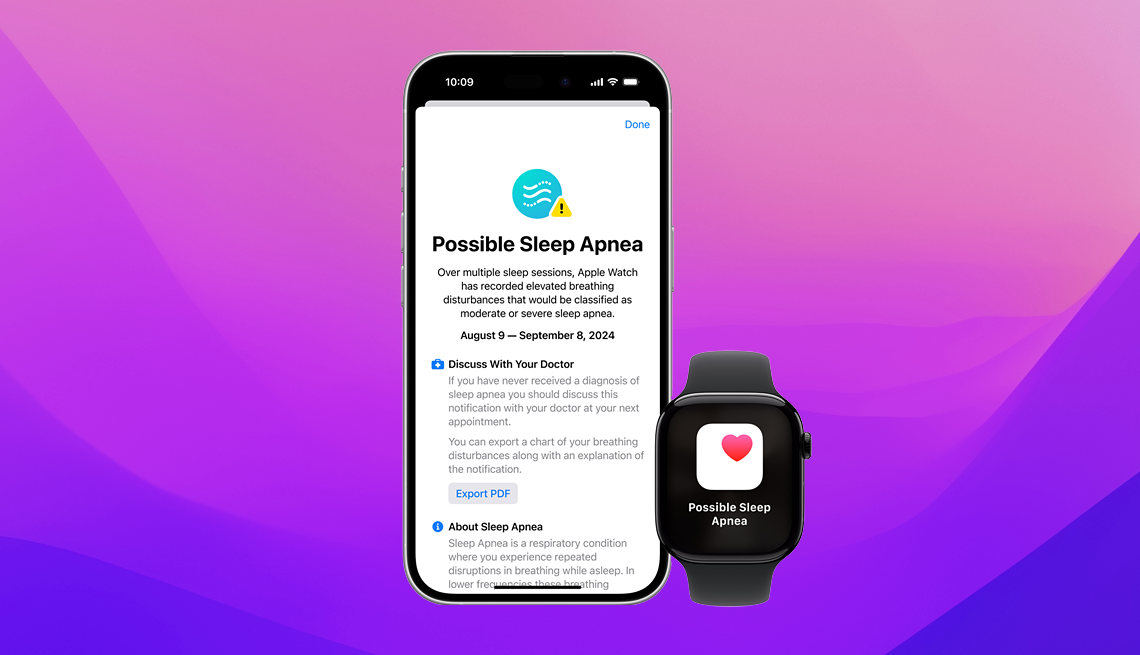

1. Sleep apnea

If you keep waking up unrefreshed even though you seem to be doing everything “right,” there may be a relatively straightforward explanation: sleep apnea. The condition, which causes you to sporadically stop breathing throughout the night, is widely overlooked, with about 85 to 90 percent of people with sleep apnea unaware that they have it, the Cleveland Clinic says. Sleep apnea is especially common in older people, affecting 17 percent of men and 9 percent of women ages 50 to 70.

So while it might be tempting to look for an explanation other than a sleep disorder to explain your unsatisfying z’s or daytime fatigue, often a sleep disorder is at least partially to blame.

“A lot of times, this kind of thinking — that something else is causing the sleep issue— only delays treatment for the sleep problem, when treating the sleep issue first can often resolve other issues,” says Shelby Harris, a clinical psychologist who is board certified in behavioral sleep medicine and serves as a clinical associate professor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

The top-line treatment for sleep apnea is positive airway pressure (PAP), which describes a range of devices that help prevent the throat from closing by increasing air pressure in the airway.

More on Health

Wake Up More Refreshed With Our Smart Guide to Sleep

43 tips to help you fight those restless, endless nights and get the slumber you need

10 Medications That Can Mess With Your Sleep

Trouble sleeping? These drugs may be to blame3 Reasons to Avoid Sleeping Pills

Sleep medication use is on the rise, especially in older adults

Recommended for You