AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Eleven

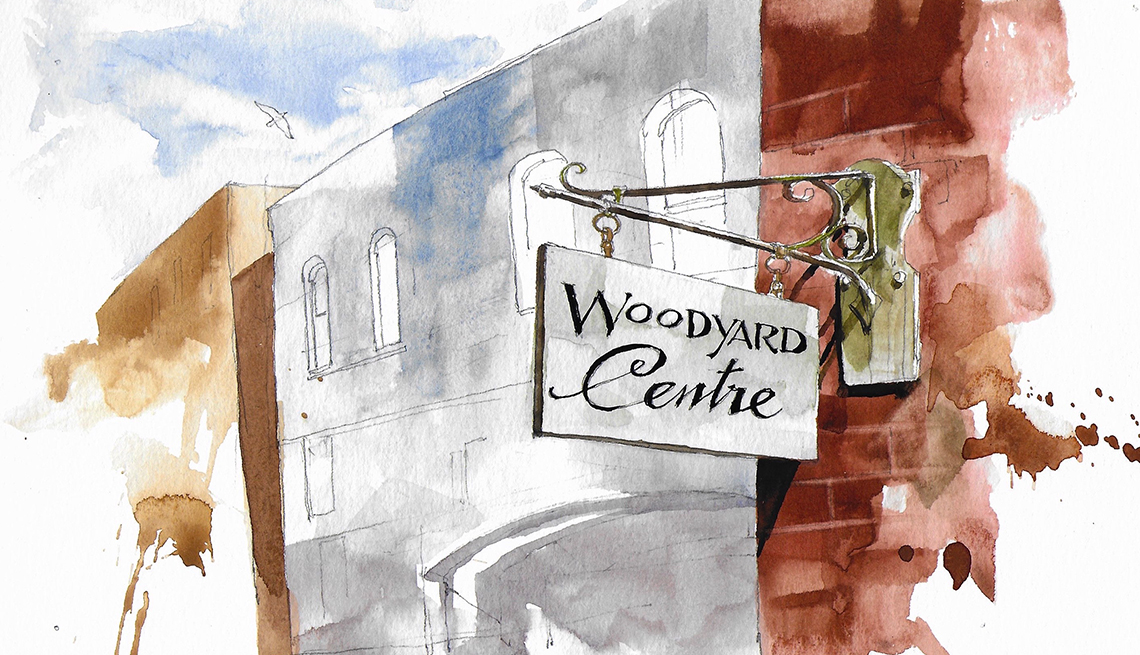

In the Woodyard kitchen, the working day was nearly over, the pans clean, the stainless-steel surfaces scrubbed. It was open to the cafe, separated by a counter, tiny with an oven and a hob on one side and a sink on the other. Matthew had been to the cafe often with Jonathan. The coffee was good and the cakes were better. A few lingering visitors were finishing tea. They passed Matthew on their way out as he was taking a seat at the table nearest to the counter. The chef, Bob, was a large man but nimble on his feet. Jonathan had once said that watching him at work was like seeing an elephant dancing. Miraculous. Bob hung a tea towel over the hob and looked at Matthew. ‘I expect you could use a coffee. I’m ready for one myself.’

Once the coffee was made, they moved to a table looking out over the river. ‘Is this about Simon?’

‘You heard?’ Matthew wasn’t surprised. Of course, the news would have spread through the place by now.

‘Saw it on the telly this morning.’ ‘He worked with you?’

The big man nodded. ‘As a volunteer. He was a lovely baker.

They taught him that in the army. Apparently, he did a couple of tours to Afghanistan. Soldiers have to eat like the rest of us.’

‘Of course.’ Again, Matthew’s perspective on Simon Walden shifted. Had the man been suffering from PTSD? Would that account for the mood swings and obsessions? ‘How did he come to be working with you?’

‘Caroline Preece asked me to take him on. Her dad’s on the board of trustees of this place and it’s not wise to upset Christopher.’

‘Why?’

Bob shrugged. ‘He’s a wealthy man and he’s used to getting his own way. He runs the board. And he dotes on that daughter of his. But Simon was okay. Not like most of the volunteers, who are pains in the arse. Chatty bloody women. He just did what was needed. I could leave him to get on with it. Some days he’d come in early — no fun on the bus from Ilfracombe — to start the bread. We do all our own baking. It would pretty well be ready when I got here. Saved me a bit of work.’

‘He didn’t drive?’

The cook shook his head. ‘He killed a child once. He never got behind a wheel again. You can understand it.’

Matthew thought Walden had confided in Bob more than he had the women with whom he was living. That made sense. They were men together, closer in age. ‘Lucy Braddick works here too?’

‘Only a day a week at the moment.’ Bob showed no curiosity in why Matthew was asking. ‘Her group at the day centre take it in turns. Not in the kitchen but waitressing, clearing tables. She’s one of the good ones, Lucy. A great little worker. And sunny. Always smiling. The customers love her.’ He paused. ‘I’m thinking of taking her on properly, paying her a living wage if the day centre is up for it. It only seems fair; she’s every bit as good as the regular staff.’

‘Would she have met Simon Walden?’

‘Well, we keep the day centre chaps this side of the counter. Health and safety. You know how it is. Anyway, no room to swing a cat back there. But yeah, they chatted to each other. Simon was brilliant with all the regulars from the centre. I think Lucy was a favourite.’

Matthew nodded and thought that was one mystery cleared up. Lucy had recognized Walden from the kitchen. It didn’t explain, though, why she’d seemed so vague about where they’d met or why he’d made the trek to Lovacott on the days before he’d died, making a point of sitting next to her on the bus.

By the time Matthew had finished talking in the cafe, it was late afternoon. Outside, there was still a bit of heat to the sun. Matthew could feel it on the back of his neck as he walked to his car. He crossed the bridge and drove into the town, planning to get to his desk at last, to catch up with what had been going on at the station, to put Ross out of his misery by allowing him to show off what he’d achieved during the day. But at the last minute he changed his mind and headed towards his old school and the big houses that looked out over Rock Park. He’d been given Christopher Preece’s address by Jonathan. He was interested to meet Caroline’s father, the man whose money had given birth to the Woodyard.

The house was detached, built in the arts and crafts style, with mellow brick and mullioned windows, small dormer windows to break the roofline, not very old but traditional. A row of trees marked the border of the garden; there was a small pond and a terrace. A pleasant garden, slightly left to run wild. Wrought-iron gates stood open but Matthew parked outside in the street. He rang the bell and the door was opened almost immediately by a middle-aged man, tall, attractive, healthy-looking, in jeans. Matthew realized he had seen him a few times before: in their old flat in Barnstaple and at Woodyard social events. He and Jonathan usually kept their working lives separate, but occasionally he was dragged along to meet the great and the good, councillors and potential donors.

‘Hello?’ It was clear that Preece wasn’t accustomed to strangers turning up on the doorstep, but this was a smart stranger so he didn’t just close the door. And perhaps there was a brief moment of recognition too. He smiled, like a politician, anxious not to alienate a voter whom he might have met before.

‘Matthew Venn. Devon Police.’ Matthew held out a card. ‘I’m here about Simon Walden. He was murdered yesterday. He was living in the same house as your daughter and her friends.’

‘Of course. I heard about it. And I’m sorry, of course I should have recognized you. You’re Jonathan’s partner. Do come in.’ A serious frown, followed by the same politician’s smile and a good firm handshake. Preece led him into a back room. A long window looked out onto a lawn, shrubs. Inside, there was an upright piano, comfortable chairs gathered around an open grate. Lots of photos of Caroline, framed music exam certificates, pony club rosettes. It seemed it had been a comfortable childhood. Until her mother had died. Matthew looked for a picture of the mother, but there was just a wedding photograph, formal. Preece and a fair, willowy woman standing on church steps. She wore traditional white and carried flowers. Nothing more recent. ‘Can I get you something? Coffee?’

Matthew shook his head. ‘Did you know Simon Walden?’

‘I met him a couple of times,’ Preece said. ‘Caroline asked me not to interfere, but I wanted to judge him for myself.’

‘Did you see him at the house in Ilfracombe?’

‘Not the first occasion. I saw him in the house a few times later when I’d calmed down.’ Preece paused. ‘I’m afraid I lost my temper when I heard she’d invited him to stay there. It seemed such a very reckless thing to do. But Caroline made it clear that her tenants were none of my business. I might have helped provide the deposit for the place but she said it was her house, her decision who lives there.’ Another of the smiles, self-deprecating, confiding. ‘You see, Inspector, it seems that I’m only welcome if I’m invited. And perhaps that’s as it should be. I still think of her as my little girl, but I do understand that she needs to be independent.’

‘So, where did you meet him first?’

Preece took a while to answer. ‘I asked him to come here. I was worried about a stranger with apparent mental health problems moving into my daughter’s home.’ Matthew wondered what Preece made of Caroline’s career choice — after all, she spent every day working with people with mental health problems — but he was still speaking. ‘As I told you, at the very least, I wanted to make my own assessment of the man.’

Preece stared into the garden. ‘I didn’t want to see Walden in the Woodyard where he was a volunteer. That would have been too formal, too complicated. I’ve always tried to leave the practical business there to the professionals. I wouldn’t want them to think I was meddling. In this case, I was, of course, but in my daughter’s affairs, not the Woodyard’s.’

‘You did get him the place in the Woodyard cafe.’ Surely, Matthew thought, that was interference of a sort.

‘The volunteering was Caroline’s idea, Inspector. Nothing to do with me.’

Matthew imagined Walden here, summoned to this calm and comfortable house. Surely it must have been an intimidating encounter. ‘What did you make of him?’

Preece thought about that. ‘He wasn’t quite what I expected. I liked him.’ He paused for a moment. ‘He told me he’d killed a child. A road traffic accident. He’d been drinking. Not enough to be over the limit but enough to lose concentration for a moment. I was impressed by his honesty. He told me he’d carried the guilt around with him ever since. We had that in common. The guilt. Survivors’ guilt. If you’ve been to the Woodyard, you’ll have heard about my wife.’

‘As you said, Jonathan Church is my husband. He explained that she’d taken her own life. I’m very sorry.’

‘Becca had suffered depression on and off since soon after we met. It was much worse in the last five years of her life. I didn’t understand it. I wanted to help but I couldn’t see how and that was a nightmare for me. I’m a control freak. I make things right. But I couldn’t make her right. And there was nowhere to go for help. The medical profession was completely useless. I think I took out my frustration and irritation on her. We had a row the night that she died. My last words to her were that she was selfish. I said if she cared at all about Caroline, she’d pull herself together and give more time to her daughter.’ He stopped and turned away. ‘That was unforgiveable and I’ve been punished ever since because that conversation is the last memory I have of her.’ He turned back to Matthew. ‘I went out to calm down, walked along the river for an hour. When I got back she’d hanged herself.’

‘And that happened in this house?’ Matthew didn’t think he’d be able to stay here with such dreadful memories. He wasn’t sure what to make of Preece. The story seemed to come easily. Was this something he’d repeated many times before so he’d become distanced from it, or was he confiding in Matthew because he was a stranger?

‘Caroline wasn’t here when her mother died,’ Preece said. ‘It was a weekend and she was at a festival. Something for young Christians. She’d developed a strong faith even before her mother’s death. Afterwards, she didn’t want to move, so I didn’t think I had the right to make her.’ He was still for a moment, lost in thought. Matthew could tell there was more to come. ‘I hadn’t expected the guilt when Becca died. I expected the grief. Missing her, missing the woman I’d loved and married. But, you see, part of me was glad she was dead. I walked into the house and saw her there, hanging from the bannister in the hall, and there was a brief moment of relief. It had been such a strain living with her, the moods and the anger, the days of total withdrawal, the helplessness because I couldn’t help her or make her well. And it was that moment that caused the guilt. That was what prompted me to get involved in St Cuthbert’s and in setting up the Woodyard.’

There was the same smile, implying that Matthew was easy to talk to, that just in those moments the two had become friends: the politician’s knack of making a person feel special. Dennis Salter, the Brethren elder who’d preached at his father’s funeral, had the same ability, the same warmth.

Matthew understood what Preece meant about guilt, though. Perhaps because of the memory that had conjured up Salter, his childhood mentor, he found himself back in the cemetery. He was watching the service to mark the death of his father from a safe distance. The crocus at his feet and the drone of the organ in his ears. He wondered if he’d felt a moment of relief too when he’d heard his dad had died? Perhaps. Because any decision about whether or not he should visit the hospital had been taken away. It made things cleaner, easier. And now he was feeling guilty again, because he hadn’t had the courage to visit, to make things right. Because he hadn’t walked round the pool of crocus to stand with his mother in the chapel of rest.

In the silence that followed there was the sound of birdsong, loud and clear, from the garden.

‘I’d grown a number of businesses in this area,’ Preece said. ‘Becca was a local girl, but I grew up in London. We met when I was here on holiday with some friends. I only moved down when we married, and perhaps, as an outsider, I could see the potential for development better than the locals.’ He was still standing, his back to the long window, the new green of the garden behind him. ‘And I’ve always been a risk-taker. I didn’t think the British love affair with cheap package holidays would continue. Not for the discerning young middle classes. I built an estate of luxury holiday flats in Westward Ho! and took on a run-down caravan park in Croyde, turned it into an upmarket chalet and glamping site. Later I diversified into bars and restaurants.’

Matthew nodded to show he was listening. Let the man explain in his own way.

Preece continued. ‘When Becca died, I’d already been thinking of selling the businesses on. I enjoyed the start-up phase, the planning, the negotiations, but found myself rather bored once they were up and running. I’m not really a details man and I was ready for a new challenge. So, being active in the charity sector wasn’t as altruistic as it might have seemed.

I started the drop-in centre at St Cuthbert’s soon after Becca died, but we needed something more professional and Caroline has made that happen. The project has developed beyond my wildest dreams. Then I was ready for something more demanding and I got behind the Woodyard. I got a buzz out of being part of a completely new organization, finding my way round charity laws and the way NGOs operate, helping to recruit a set of trustees. We’ve got a good team there now with a mix of skills: an accountant, a lawyer, a couple of senior social workers and a former building society chief. It fended off the guilt and the grief, at least for a while. And it made Caroline proud of me. That was important.’ He paused. ‘I know it’s an old-fashioned thing to say, but my reputation is important to me, and I see the whole of the Woodyard as my baby now. My legacy. I’ll always be associated with it.’

This, Matthew thought, was the politician talking again. ‘You say you liked Walden. Was there anything about him that made you anxious about the fact that he’d be sharing the house with your daughter and her friends?’

‘There was an intensity about him that I found a bit unnerving. As if he didn’t have a protective skin of any description. Perhaps he was too honest for his own good.’ A pause again. ‘Actually, after meeting him, I was more worried about how he’d fare in that house with two confident young women than whether he’d be any kind of danger to them. Gaby Henry has a sharp tongue and I’m not sure I’d be able to live with her. She’s entertaining for an evening but I know she’d exhaust me after a while.’

‘When did you last see Walden?’

‘About ten days ago. Caroline invited me to have dinner with them.’

‘Ah,’ Matthew said. ‘One of the famous Friday feasts?’ ‘You know about them?’

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members