AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Thirty-One

ON SATURDAY MORNING MATTHEW WOKE EARLY. He’d gone to bed before the others and, wandering into the kitchen, he saw that they must have stayed up to load the dishwasher, clean the surfaces. Everything was tidy. He felt a ridiculous fizz of resentment, because there was no longer any excuse for his lingering anger. He made coffee and was just about to take a cup through to Jonathan when his husband came in, bare foot, wearing a short dressing gown.

‘I’m sorry about last night,’ Jonathan said. ‘I should have realized the last thing you needed in the middle of an investigation was surprise sleepover guests, but you know how I get carried away when I’ve had a few glasses. And it was Friday. I hate spending Friday night on my own. It seems blasphemous somehow. Fridays should be shared and celebrated and I wasn’t sure how long you’d be.’ He nodded towards the bedroom where the women were sleeping. ‘They won’t be here for long. They need to be back home this morning. I promised to make them breakfast. Why don’t you try to get back for lunch? They’ll be gone by then.’ He reached into the fridge for eggs and a bag of mushrooms.

‘I doubt if I’ll be able to get away.’ Matthew realized that sounded churlish. ‘But I’ll try. It’s a lovely idea.’

‘So I’m forgiven then?’ He sounded anxious, as though these were more than trite words. The adopted boy, worried about being disowned, searching for a real place to belong.

‘Of course.’ Because Matthew always forgave him. He thought he’d forgive Jonathan anything.

The police station was quiet. Ross was already in and staring at his computer screen. Matthew had just settled at his desk when there was a phone call from Jen asking if it would be okay if she came in a bit later.

‘I really need to spend a bit of time with the kids. Ella and Ben will forget what I look like soon and if I don’t do some food shopping, they’ll start eating each other.’

‘Yeah, sure.’ Matthew hoped this wasn’t an excuse, that she hadn’t had a wild night out and just staggered home, too rough to work.

‘You got my message about Jonathan’s conversation with Christine Shapland and the meeting with Caroline and the St Cuthbert’s clients? I didn’t get anything useful. Sorry.’ Jen sounded sober enough.

‘Yes.’ Matthew had hoped to discuss Woodyard affairs with Jonathan the night before, to ask his opinion and share ideas. Matthew thought he should have done that instead of rushing out to Lovacott to talk to the Salters. Now he saw that had been a wasted trip. He hadn’t thought it through sufficiently before challenging Grace and it had left him only frustrated and angry. And Salter had been warned that Matthew knew about his domestic life. He’d become even more closed and secretive.

‘Thanks,’ Jen said. ‘I’ll be in later. If anything important turns up, just give me a ring.’

Matthew replaced the receiver and wandered over to Ross’s desk. ‘Have we got anything from the CSIs after the sweep on Walden’s flat in Braunton?’

If there were fingerprints not on the system, he’d be interested to know if there were any not yet identified. He’d love to find evidence that Salter had been in the flat. He pictured asking the man in to the station to have his prints taken, the powder on his fingers like a mark of shame. Salter wasn’t a stupid man, though. If he’d carried out the search of the flat, he would surely have worn gloves. And Matthew needed to be careful — his antipathy towards the man was clouding his judgement. He had no real evidence that Salter had been abusive or that he was involved in any way in Walden’s death.

‘I was just about to chase it up.’

Matthew left it at that. He still felt guilty about losing patience with Ross in front of other officers; he hated losing control. Feeling trapped and restless, he went back to his glass corner of the open-plan space. He wished he could find a more tangible link between Dennis Salter and Simon Walden. There was no evidence even that the men had met. Salter’s sly insinuation that Jonathan might be involved somehow with the investigation, that Matthew was in a position to protect his husband, made him think again that he should withdraw from the case. But it also made him angry. He knew, with a certainty that was almost religious, that Jonathan could not be involved in murder or kidnap.

I’ll give it until the end of the weekend. If we haven’t cracked it by then, I’ll take it upstairs. I’ll tell Joe Oldham that Jen Rafferty is perfectly able to manage this on her own.

Through the glass partition, he watched Ross making his phone calls. There was a sudden, silent mime of excitement, a fist in the air. Ross waved over to him and once more, Matthew paced across the space between the desks and computer terminals.

‘What is it? Have you won the lottery?’

‘Better than that!’

‘Go on then, tell me.’ Matthew wasn’t a violent man but there were times when Ross provoked him so much that he wanted to slap him, and he was in a mood to lash out.

‘The CSIs have come back with their first report on Walden’s Braunton flat and they’ve found a couple of fingerprint matches. We have confirmation that Christine Shapland was there.’

‘Ah, I think we already guessed that was the case.’

‘There was another match, though.’

‘Give me a name, Ross. Stop messing about.’

‘You know they took the prints of the women from Hope Street for elimination?’

‘I didn’t know that but it makes sense. A good decision.’

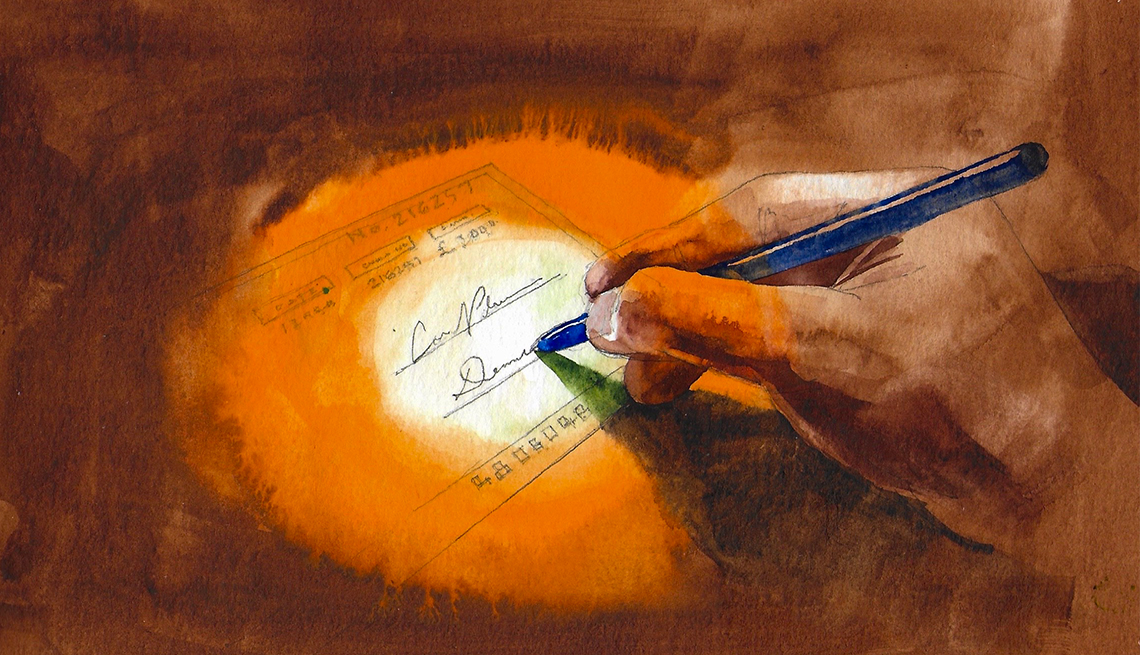

‘It seems that Gaby Henry had been in the Braunton flat. There’s no mistake. They found her prints in the bathroom and on the chest of drawers in the bedroom.’

Matthew thought about that and wondered why he wasn’t more surprised.

Back in his cubby hole, he phoned the landline in Hope Street. He thought nobody was in, or they were all in bed, and it would just go to answerphone but it was picked up. ‘Caroline Preece.’ She sounded tired and unwell.

‘This is Matthew Venn. Could I speak to Gaby?’

‘She’s not here, Inspector. Gaby runs a watercolour class for the U3A in the Woodyard at lunchtime on a Saturday. Not her favourite thing but needs must. She left half an hour ago. She said she wanted to do some of her own work — there’s a painting she was hoping to finish — before the students turned up.’

Matthew found Gaby alone in her studio at the Woodyard. She was working on the painting of Crow Point. ‘Is it almost finished?’ He couldn’t see how she could make it any better. It had a luminous quality. Light behind cloud. He lost himself in the image for a moment.

‘Yes.’ She lowered her brush, but she couldn’t stop looking at the painting. He still didn’t have her full attention.

‘You met Simon for coffee that morning, didn’t you? At least, he had coffee and a bacon sandwich and you had herbal tea.’

She set her brush on the shelf at the bottom of the easel and now she did turn to face him.

‘How did you find out?’

He shrugged. ‘Routine policing.’ Only then did he see the green jacket, hanging on a hook on the back of the door. ‘A witness saw you together in the cafe in Braunton and described what you were wearing.’ She didn’t reply and he continued: ‘Were you in a relationship?’

‘I’m not sure that’s what you’d call it.’

‘But you visited his flat in Braunton. You knew he had somewhere else to live.’

She didn’t answer.

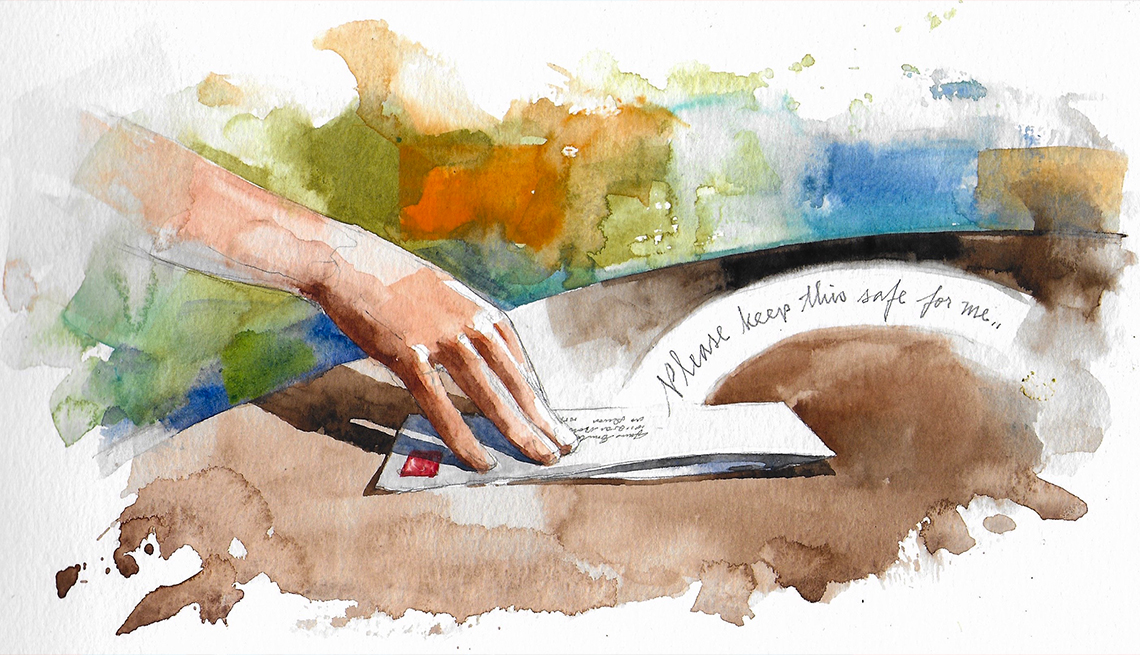

‘We know that you went there,’ he said. ‘We found your fingerprints.’

Still she stared back at Matthew in silence. ‘Did you kill him?’

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members