AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Twenty-Seven

JEN RAFFERTY SAT IN THE SHAPLANDS’ small, dark cottage, which seemed to have grown out of the marsh, listening to her boss’s husband talking to Christine. She’d met Jonathan a few times before — at a work’s Christmas do and once at their house when she’d picked Matthew up for an early shout — but Matthew liked to keep home and work life separate and she’d never really got to know the man. Dorothy Venn, who’d stuck with Susan Shapland throughout the hospital visit, wasn’t there. Matthew had said that he’d been rejected by his family long before his marriage, but Jen thought a gay relationship would be hard for a fundamental Christian to swallow. Perhaps the woman couldn’t even bear to be in the same room as her son’s husband.

Outside, the mist was lying low over the creek and damp seemed to ooze through the walls and into the room. There was a coal fire in the grate and Jen felt she’d slipped back more than fifty years to when Susan Shapland was a young woman and North Devon was a very different place. There was a pot of tea on a lace mat and a plate of scones already buttered.

Jonathan and Christine sat in chairs closest to the fire and the man’s voice was so low that at times Jen struggled to make out what they were saying. Christine was wearing jogging bottoms and a tracksuit top, grey with pink edging. Her cheeks were flushed from the flames. Despite the chill outside, Jonathan was still in his signature shorts and T-shirt. Jen wondered if he’d worn shorts to his wedding, and thought they made an odd pair, Matthew always suited and smart, Jonathan looking as if he’d just wandered in from the beach. She was sitting at the table, phone and notebook in front of her. She’d record the conversation and take notes too, because her impressions would be as useful as Christine’s words.

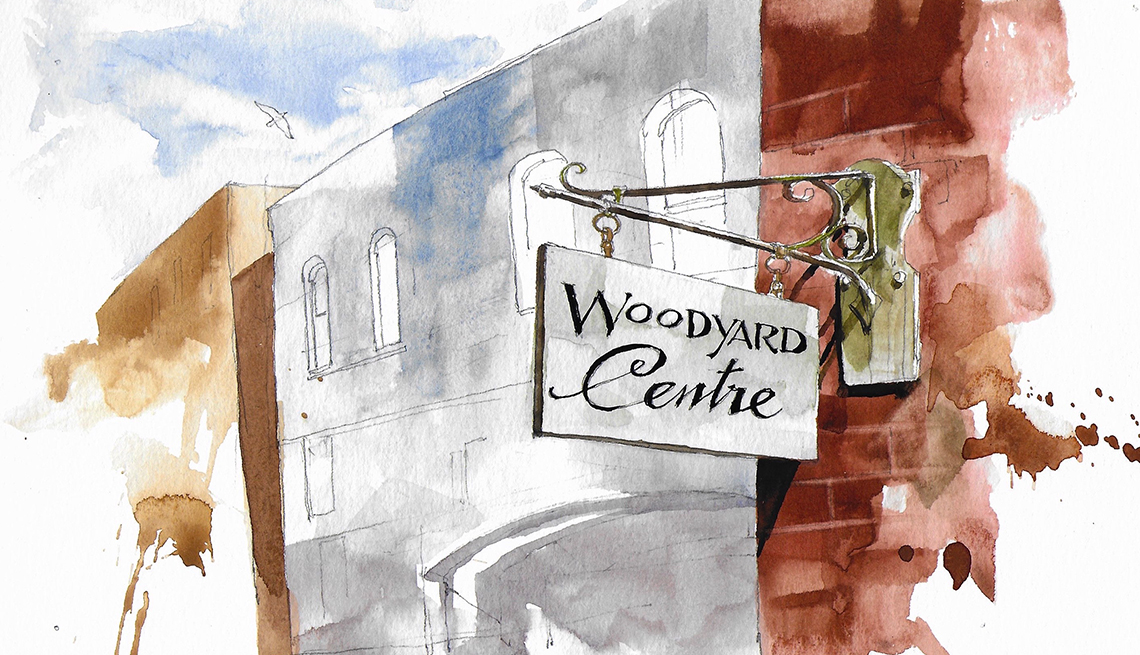

‘The main thing to say is that you’re not in any trouble at all.’ Jonathan’s voice was warm and easy. Reassuring. ‘You did nothing wrong. Nothing at all. We just want to find out what happened. That’s what this chat is about. And because it’s nice for me to escape from the Woodyard for a bit and eat your mother’s scones.’

Christine looked up at him, but there was no answer. She couldn’t tell where this was leading.

‘So, let’s start at the beginning. You thought your uncle Dennis was going to pick you up from the Woodyard on Tuesday night. You’d stayed with him and your auntie Grace on Monday and he’d dropped you off that morning.’

Christine nodded.

‘But when you left the Woodyard on Tuesday afternoon, you didn’t see him?’

Christine looked at her mother, who was sitting at the table next to Jen, crumbling a scone on her plate.

‘You can tell him the truth,’ Susan said. ‘The Brethren will never find out.’ Jen saw that it mattered even now what the Brethren thought of her. ‘It’ll just be you and me now, girl.’

‘Someone came up in a car,’ Christine said. ‘They told me they’d give me a lift back to Lovacott. That it had all been organized.’

‘Was that a man or a woman, Chrissie?’ Jonathan asked.

‘A man.’

‘Can you tell me what he was like?’ She seemed thrown by that.

‘Well, was he dressed like me? Shorts and T-shirt?’

That made her laugh. ‘No! He was smart, like Uncle Dennis at meetings.’

Susan jumped in. ‘She means a jacket and tie.’

‘Did you know the man? Had you seen him before? If he was a friend of your uncle’s, he might have been at meetings with you.’

Christine shook her head. ‘I’d never seen him before.’

‘That’s okay. You got into the car with the man. Were you in the front or the back?’

‘In the back.’

‘So, it was like you were in a taxi?’ Christine nodded.

‘What happened then, Christine? Just tell us as if it was a story. Your story.’ Jonathan leaned back in the moth-eaten armchair as if he had all the time in the world. Outside, the mist still lay over the water. It could have been a winter’s evening. There was the white flash of a swan taking off from the creek, the sound of wingbeats.

‘We got to a house,’ Christine said. Her speech wasn’t quite clear and Jen struggled to make out the words, but Jonathan knew exactly what she was saying.

‘Your uncle and auntie’s house?’

‘No! Not a big house like that.’

‘A cottage then, like this? All the rooms on one floor?’ Jonathan asked. Jen thought he had the patience of a saint. No way would she have been able to prise this information from the woman. She was fine in interviews where she could get inside the head of the witness and see the world through their eyes, but this was a very special skill.

‘All the rooms were on one floor,’ Christine said, ‘but we had to go up some stairs to get there.’

‘So, it was a flat?’ A nod.

‘Was it a big building with lots of floors, lots of flats?’

‘No! Just one flat over a shop.’

Walden’s flat, Jen thought. They took her to Walden’s flat. They knew he wouldn’t be there because he was already dead. We could have arrived there soon after he took her to the pond. She couldn’t help interrupting. ‘Do you know what kind of shop was under the flat?’

But Christine just shook her head.

‘What did you do in the flat, Christine?’ Jonathan took up the questions again.

‘I watched the telly.’ A pause. ‘I like the telly.’

‘With the man who’d driven you there?’

‘He stayed for a bit. He gave me some crisps and a bar of chocolate. A can of pop.’ She shot a look at her mother. Perhaps she didn’t get fizzy drinks at home.

‘Did you ask why he’d picked you up?’

‘He didn’t say anything.’

Jonathan leaned forward and took Christine’s hand. ‘Did the man hurt you in any way? Touch you?’

‘No,’ she said. ‘He asked me lots of questions. It was like a test. I couldn’t answer anything.’

‘What sort of questions?’

‘I don’t know!’ She was close to tears. ‘I didn’t understand what he wanted. I said I wanted to come home. Back to my mum’s house. I didn’t want to stay in the flat and I didn’t want to go to Uncle Dennis and Auntie Grace’s place. I just wanted to come home.’

Jen could hear Susan muttering beside her. Some sort of apology or prayer. She turned and saw that the woman was weeping. Jen pulled out a tissue and passed it across.

Christine was speaking again. ‘The man said he couldn’t take me to Mum’s because he had to leave. He had important things to do. I could make myself at home until my uncle came. There was a bedroom if I wanted to go to sleep. More chocolate and more pop in the kitchen.’

‘And did your uncle come?’ Jonathan asked.

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members