AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Three

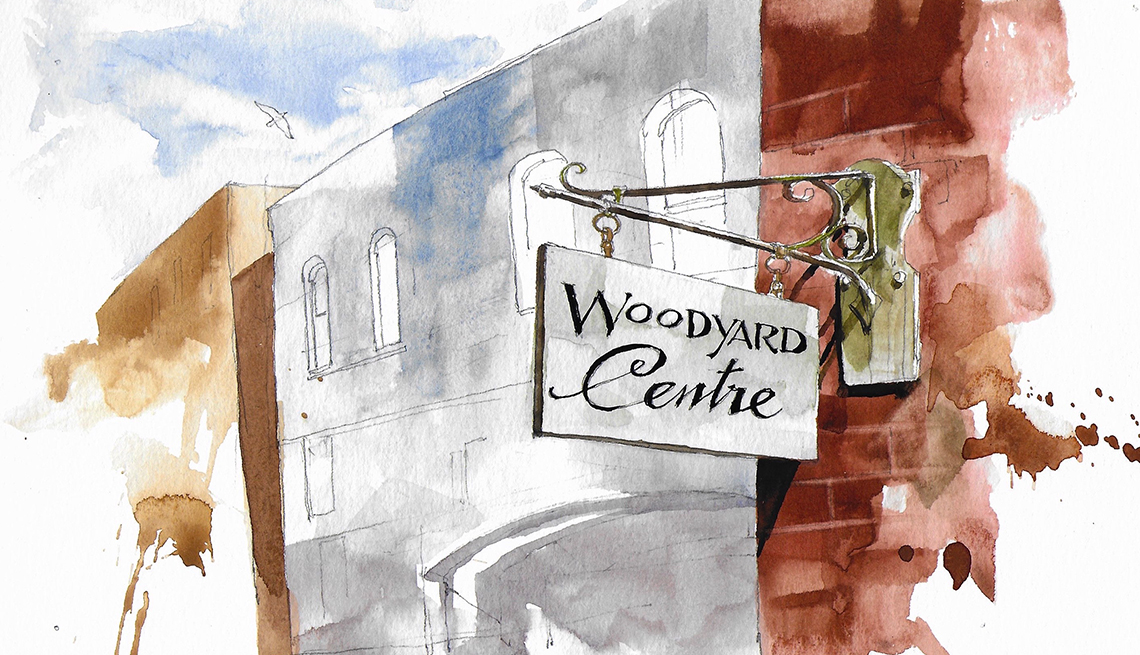

THE WOMAN HAD THE DOOR OF the toll keeper’s cottage open almost before they’d got out of the car. There was something hungry, desperate, about her need for information.

‘I’m DI Venn,’ Matthew said. ‘This is DS Rafferty.’ ‘Hilary and Colin Marston. You’re here about the body.’ She looked them up and down. ‘You’re detectives. Unexpected death, your chap out there said, but this isn’t natural causes, is it? Not just a heart attack or an accident. There wouldn’t be all this fuss for an accident.’

‘Perhaps we could come in and ask you a few questions?’ ‘Of course.’ She backed away and they were let into a hall.

A pair of wellingtons stood at the foot of the stairs and a waxed jacket hung on a peg next to a smart black coat, which seemed out of place in the cottage.

It was hard to age her. The hair had been dyed almost black and she was wearing make-up. Late fifties? Matthew wondered. Early sixties? She was big-boned and strong, taller than the man who stood behind her in the passage. She wore black trousers and a black jacket over a white top, office wear for a middle-manager, Matthew thought. The coat must belong to her. Again, out of place, here on the edge of the marsh.

Her husband seemed more at home. He was short and round, a woollen jersey stretched over his stomach. Matthew thought they must have moved in recently; there was a hint of a Midlands accent and he’d seen the previous residents – an elderly couple who’d come out to collect the toll and have a chat – at Christmas. Perhaps the automatic barrier had been installed because the couple had retired. Or one of them had died. It seemed all he was thinking about today was death. The woman led them into a living room and the man followed. The room was cluttered, a little untidy. Uncared for. It was as if they were camping out here. Matthew wondered what had brought them to the house. They all sat awkwardly for a moment, staring at each other across an orange pine coffee table.

It was Jen Rafferty who spoke first while he was still taking in the surroundings. ‘If you could just repeat your names for our notes.’

‘Hilary,’ the woman said. ‘Hilary Marston, and this is my husband Colin.’ Then she started speaking again and Matthew’s curiosity about the couple’s background was answered without need for any questions. ‘Colin took early retirement, redundancy really. He worked in the legal team for a car manufacturer; that’s all changed of course. Everything’s outsourced these days, nobody has any pride in British industry now. And our area had changed – people from outside moving in. One time, you knew all your neighbours. Not any more.’

Matthew broke in. Jen leaned so far to the left that she’d only recently become reconciled to the Labour Party. She couldn’t cope with intolerance, and he could tell that she was already a bit prickly. ‘What brought you to North Devon?’

‘We’d been here on holiday,’ Hilary Marston said. ‘Loads of times. We thought: That’s the place for us to end our days. We never had any kids to think about and we loved it to bits. So quiet and so clean.’ A pause. ‘No foreigners.’

‘Well, it’s certainly very quiet here.’ Jen had an edge to her voice that only Matthew picked up.

‘Yeah, well,’ Hilary said. She shot a look at her husband. ‘Sometimes you can have too much of a good thing. We’re only renting here – it certainly wouldn’t be our choice of furniture – and it wasn’t the best decision we ever made. Maybe we saw the cottage through rose-coloured glasses when we viewed it in the summer. Colin’s a birdwatcher. The marsh is his idea of heaven. It’s not mine. We won’t be staying. We’ve put an offer in on a house in Barnstaple, where there’s a bit more life.’ She paused. ‘A bit more culture. And it’ll be closer to work for me.’

‘What is your work?’

‘I’m a mortgage advisor with a bank in town. I was planning to retire too, but this job came up. Only part-time, but the extra cash is always useful.’

Matthew turned to Colin Marston. ‘Were you out on the marsh birdwatching today?’

The woman, her resentment palpable, didn’t give her husband the chance to answer. ‘He’s out there every day.’

Colin Marston ignored her. Perhaps her sniping was so common that it had become no more than background noise for him. ‘I do a daily census.’ He spoke with a quiet pride. ‘Real ornithological research is about regular counts of common birds. I’m not just a lister, interested in rarities.’ The last sentence was spoken with a sneer.

‘Does your research take you onto the beach too?’

‘That’s part of my census walk. I end up there. I count the gulls on the shore and come inland at Spindrift, then back along the toll road home.’

Spindrift. Our house. Matthew thought now he might have seen the man walking past, anonymous in the waxed jacket and wellingtons they’d seen in the hall, binoculars round his neck. Out in all weathers.

‘What time were you there today?’ Jen asked.

Colin Marston left the room. Through the open door, Matthew saw him take a soft-back notebook from an inside pocket of the jacket. He sat down again and opened it.

‘Twelve thirty-five.’ He looked up. ‘I note the time at every watch point. My own way of working. Citizen science in action.’ In an armchair in the corner Hilary rolled her eyes. Matthew thought it must be a strange marriage if they had so little in common, if she could be so dismissive of her husband’s passion.

‘Did you see anything unusual while you were walking today?’ He was aware of a silence and stillness in the room. An awareness of danger or, more likely, excitement. Perhaps it was a shared passive voyeurism that kept the couple together. ‘I didn’t see a body on the beach,’ Marston said. ‘I asked your constable where it was and I know that I’d walked that way. I would have seen it.’

‘But did you notice any strangers? You’d know the regulars if you’re out every day.’

There was another silence, broken by the sound of a car pulling up outside. Matthew recognized it as belonging to Sally Pengelly, the pathologist. The barrier was raised and the car drove on.

‘Who was that?’ Hilary was on her feet.

‘Just one of the team.’ Matthew turned back to the husband. ‘So, Mr Marston, any strangers?’

‘There are always one or two people I don’t recognize. Even at this time of year, there are visitors. And I don’t take much notice unless they’ve got a dog that disturbs the birds while I’m counting.’

‘But today.’ Matthew was a patient man. ‘You must be a good observer, used to registering detail.’

The flattery appeared to have worked. Marston looked back at the notebook and seemed to be reliving his walk on the shore. ‘There was a couple, a man and a woman. He was in a suit, not really dressed for the beach. She was a bit younger and she was wearing jeans.’ He paused. ‘I was watching something I thought might be a little gull and they flushed it.’

Matthew was thinking the man in the suit seen by Marston couldn’t be their victim because the clothes didn’t tally, but Marston was still speaking.

‘They were walking hand in hand and they stopped once to kiss. Not just a peck, if you know what I mean. As if they’d not been together for a long time.’ He stared out of the window. ‘I wondered if they might be having an affair, because they came in two cars and there was a sense that they were doing something dangerous. Exciting.’ His voice was wistful.

‘You saw the cars?’

‘Yes. They climbed the dunes and after a bit I followed them.

I wanted a better view of the birds near the tideline.’

Jen shot Matthew an amused glance. Yeah right! Not that you were hoping to catch them making out.

‘I saw them getting into their cars. I didn’t get the reg of either of them, though. Pity, they might have been useful for you.’

‘But you do remember the make of the vehicles? The colour?’ ‘Of course!’ Marston almost sounded offended that the question had been asked. ‘As Hilary said, I used to work in the car industry. Behind the scenes, working on contracts, but it’s still in my blood. One was a red Fiesta. A few years old.

That was the woman’s. And a black Passat.’ ‘You saw them drive off?’

Marston paused for a moment. ‘I saw the man drive off. The woman was still in her car, looking at her phone, when I dropped down onto the beach.’

‘Did you see anyone else?’ The low sun must have been streaming in through the window all afternoon and the heat had been trapped in the small room. It seemed airless.

‘One guy in the distance.’ A man, it seemed, held less interest for Colin Marston than a couple.

‘Could you describe him?’

‘He was a long way off, close to Crow Point.’ Colin set his notebook on the table in front of him.

‘And he was on his own?’

‘Yeah. Though maybe he was waiting for someone. He didn’t seem to move while I was there. He was still on the beach when I headed back towards Spindrift.’ The man looked up sharply. ‘You live in the house there, don’t you? I thought I knew you. I’ve seen you in the garden and going through the toll.’

Matthew didn’t answer. Instead he asked another question of his own. ‘How many cars were parked there when you made your way inland?’

‘Just a Volvo. They’re regulars. An older couple.’

Matthew nodded to show he understood. Those would be the people seen by the constable on duty outside. It was so warm in the room that it was an effort to move. He stood up and thanked the couple for their help.

‘What happens now?’ Hilary was on her feet too, leaning forward, desperate for more information.

‘We continue with our enquiries,’ Matthew said. ‘Someone will be in touch if we need to speak to you again.’

As he stopped to unlock the car he saw both the Marstons at the window, staring out at them.

The CSIs’ vehicle passed them as they were getting into Matthew’s car, and they must have worked quickly because by the time he and Jen arrived at the scene, the tent had been erected and a white-suited team were doing a finger-touch search of the surrounding sand. Ross was standing well away, still pacing.

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members