AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Twenty-One

MATTHEW WAS VISITING ROSA HOLSWORTHY and her parents when news came through that Jen had been right about Simon having another home of his own. He’d gone to visit the Holsworthys on impulse, because he’d forgotten to ask anyone else to do it the night before. Besides, it was close to the police station, in the terrace of houses that had once looked out towards the cattle market that had long gone, and he was glad of the chance for a walk.

Rosa was younger than Lucy Braddick, thinner, dark-haired. Less mature. Matthew wouldn’t have known she had a learning disability apart from a vague look of anxiety in her eyes, the sense that the world was a mystery to her and not somewhere she felt at ease. Her legs jiggled as if she found it impossible to keep still. She flashed him a grin when she was introduced to him. ‘Are you all right?’ As if she needed to make sure that everyone around her was settled, comfortable. As if she wanted to please them. Or it could have been a verbal tic. Her parents were both at home with her. Ron Holsworthy walked with a stick.

‘Arthritis,’ his wife said. ‘He’s had it since he was a young man. He had to give up his job and he’s in terrible pain. The social took his benefit away; they say he could work if he tried. I do nights in an old folks’ home.’

‘It must be a struggle.’

They were wary of him and had only asked him in when he insisted. Matthew thought their whole life had been a struggle: against bureaucracy, doctors, social workers. They would have been suspicious of anyone in authority turning up on the doorstep.

‘You took Rosa out of the Woodyard.’

‘She never really liked it,’ Ron said. ‘Not in that big old place. It wasn’t the same as the centre they had before.’

‘Nothing happened? To make you take her away?’

‘No, there was nothing like that,’ Janet, the mother, said. ‘We’d just rather have her at home. She’s company for Ron when I’m working and she’s a good girl. She looks after him, makes him a cup of tea, helps him to the bathroom when he needs to go.’

Matthew nodded. He could understand why the couple had decided to keep their daughter at home. She was as much a carer as someone who needed to be looked after. ‘She was a friend of Christine Shapland, in the old day centre. Christine’s gone missing. I wonder if you have any idea where she might be.’

The couple looked at each other in horror. And vindication perhaps that they’d made the right decision in keeping their daughter at home.

‘No,’ Ron said. ‘We haven’t seen Christine since Rosa stopped going to the Woodyard. We keep ourselves to ourselves mostly. I hear from Maurice Braddick occasionally and he’s been over for tea with his daughter. But that’s once in a blue moon. Usually I go days without seeing a soul. Janet has to catch up on her sleep. There’s only Rosa. I’d be lost without her.’

Matthew was thinking again that the Holsworthys had their own reasons for keeping Rosa at home when the call came through that they’d tracked down Walden’s secret accommodation.

Now, Matthew stood with Ross outside the betting shop, looking out for Jen. Ross had picked Matthew up at the police station and they’d travelled to Braunton together. They must have looked like reluctant punters, hanging around on the pavement. Ross was all for going inside and asking if the bookies’ manager had a key to the flat above, but Matthew decided to wait for a while — he wanted to get a feel for the neighbourhood first — and moved them down the street a little so they wouldn’t draw attention to themselves. This was a still a place for locals and they were already attracting attention. There was a convenience store on the corner and a hardware shop, a bakery selling cakes with brightly coloured icing. Nothing healthy. Nothing here for the tourists. The breeze was still westerly and mild. Matthew imagined Walden living in the flat, letting himself out occasionally to buy food and booze. Because he’d been troubled here. Depressed and guilty, drinking heavily. Otherwise, why would he have turned up at the church in Barnstaple looking for salvation? Why would he have moved into the house in Hope Street?

He walked into the convenience store, leaving Ross outside. The place was almost empty; it was too late for schoolkids buying sweets on their way to school, too early for people looking for lunchtime snacks. On the shelves behind the counter were jars of old-fashioned confectionary: sherbet lemons, rhubarb and custard chews, humbugs. This must have been where Walden had bought the sweets he’d given to Lucy. Matthew showed the man behind the counter Walden’s photo.

‘Do you recognize him?’

The shopkeeper was of South Asian heritage, shiny-haired, handsome. He looked up from his phone and considered the picture. ‘Yeah. He was a regular for a bit, then he didn’t come in for a while. I thought he’d moved away from the area. But he’s been back again a few times more recently.’

‘He’s the guy that was killed out at Crow Point. We think he used to live round here.’

The man shook his head, as if this meant nothing to him. There was a pile of North Devon Journals on the counter, the headline — Man killed at local beauty spot — was large and dramatic. But it seemed that he sold the papers; he didn’t read them.

‘Can you tell me anything about him? Did he have any friends round here?’

‘I’m sorry.’ The shopkeeper sounded genuine. He was giving Matthew his full attention now. ‘When I first met him, he came into the shop every couple of days, that’s all I can tell you.’

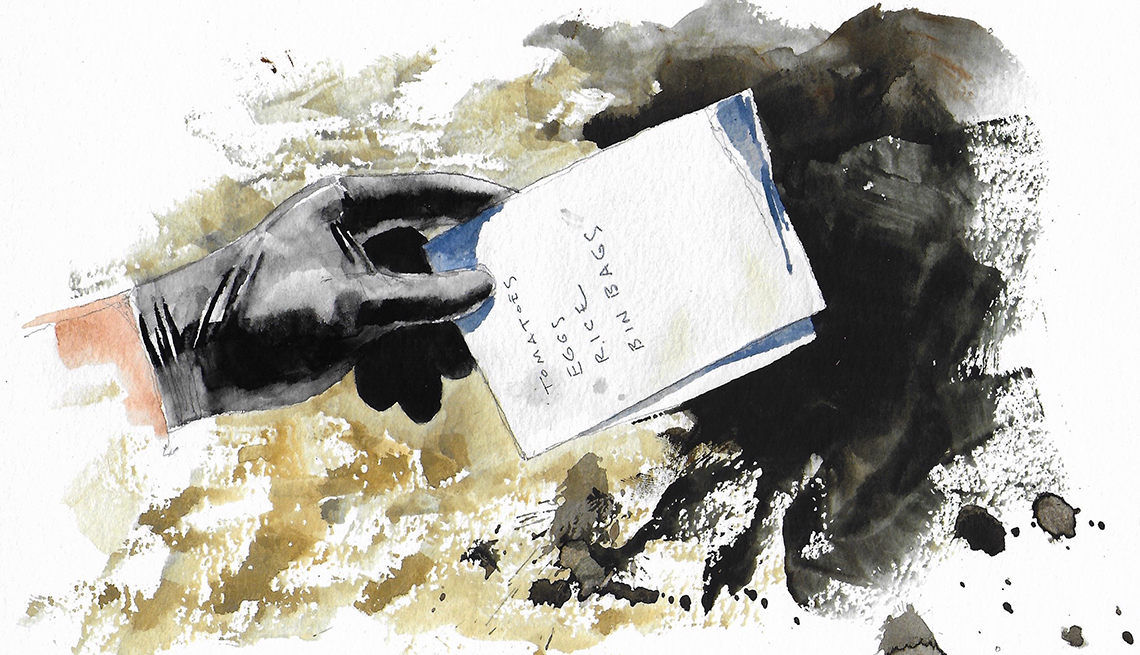

‘What did he buy?’

The man could answer that. ‘Tea, milk, bread. And booze. Always booze.’ A pause. ‘I think he must have given up drinking, though, because he’s been back a few times recently and now he’s just buying sweets. Perhaps it helps. Like when people give up the fags.’

Through the glass door, Matthew saw Jen walking down the street towards them. She was wearing a long raincoat, reaching almost to her ankles, and pulled it round her to keep off the drizzle. Her head was bare and the red hair was a blast of colour in the greyness. She stepped off the pavement to let an elderly woman with a shopping trolley walk past. Matthew thanked the shopkeeper and went outside.

‘Sorry to keep you waiting. I’d been talking to Caroline at St Cuthbert’s and I couldn’t just dash away without saying goodbye.’ Jen pulled the key from her pocket, like a conjuror lifting a rabbit from a hat, with a flourish and a grin. ‘I hope it works after all this. I’ll look a right twat otherwise.’ She held it out so they could see the albatross key ring. ‘Gaby Henry found it in a pile of washing Walden had left in their machine.’ It did work. The key turned easily and smoothly in the lock.

The door to the flat went straight from the pavement and was right next to the entrance to the betting shop. Inside, a narrow, bare staircase. They stood just inside the door to pull on scene suits, away from public view, struggling in the cramped hallway. The space was lit by a bare bulb that swung above them.

‘Hello!’ Matthew shouted up the stairs. He still had the irrational idea that they might find Christine Shapland here, and he didn’t want to scare her. Three police officers looking like something from a horror film in suits and masks would look like aliens, hardly human. There was no response and he went up.

He’d been expecting a bare, clear, organized space, like Walden’s bedroom in Ilfracombe. The man had been in the army. Even at times of distress it would be his habit to be tidy. But they walked into chaos. The stairs led straight into the living area, a kitchen and living room separated by a breakfast bar. The floor was scattered with cutlery and broken crockery, drawers had been turned upside down, dry food had been emptied from packets and there was a blue snow of washing powder on the grey lino. Beyond the breakfast bar there was a small sofa and a cupboard on which a television stood. The cushions had been pulled from their covers, the base of the sofa had been slashed and the contents of the cupboard now lay on the floor. The detectives stood where they were.

‘What do you think?’ Ross said. ‘Did Walden lose it? Have some sort of psychotic episode and trash the place?’

‘I don’t think Walden did this.’ Because although it seemed like random mayhem, Matthew thought this was a search. Someone in too much of a hurry, or too desperate to be careful and quiet had been through the place. They’d been thorough. If they’d been looking for something specific, it would have been found. It would be unlikely that a police search would find anything now. He tried to keep his thinking slow and methodical, but the senseless mess jangled his nerves and made it hard for him to think straight.

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members