AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Twenty-Nine

GABY HAD AGREED TO SPEND THE AFTERNOON with Caz and her father, Christopher Preece. Gaby still wasn’t quite sure how she’d allowed herself to be talked into it. Caz had taken her aside after her appearance at the jazz cafe the night before.

‘What are you doing tomorrow afternoon?’

‘Nothing much. I don’t work on Friday afternoons.’

‘Will you come out with Dad and me?’ Her voice had been strangely pleading and Gaby had thought Caz didn’t ask many favours, so she’d go along with it, but it had seemed an odd request. ‘He’s suggesting a walk,’ Caz said. ‘A bar meal afterwards.’

‘Don’t you want some time on your own with him?’ They’d looked across at Christopher who was standing at the bar, buying drinks for them all. Gaby had thought she wouldn’t mind the man as a father.

‘It’s the anniversary of my mother’s death,’ Caz had said. ‘I couldn’t bear it if he got sentimental about her. He won’t if you’re there.’

Gaby had been made receptive by the response to her singing, and several glasses of cava. ‘Okay,’ she’d said. ‘Why not?’ She’d thought that at the very least she’d get a free meal.

Now, in the quiet house, drinking coffee together before leaving to meet the man, Caz started talking about her mother’s death for the first time in any detail. Gaby just listened.

‘I was away from home,’ Caz said. ‘A retreat for the weekend with the church youth group. We’d all left our phones behind. It was part of the deal. The guy running the centre came to my room and told me my mother was dead. No other details. Not how she’d died. A friend drove me home, but I told her not to come in. Dad was there, waiting for me. He told me my mother had killed herself, she’d hanged herself.’ Caz paused for a moment. ‘I lost it. Started yelling. Blaming him.’

Gaby found it hard to imagine Caz, usually so controlled and contained, losing it, but her friend was still talking.

‘I said some hateful stuff: I thought we were in this together. Working to keep Mum safe. How could you let this happen? He’d tried to take me into his arms but I pushed him away. I know I should forgive him, but part of me can’t quite.’ She looked up at Gaby, her eyes very big behind her glasses. ‘It’s ten years, so perhaps we should make our peace. But I don’t want to be on my own with him. Not on this particular day. Do you understand?’ Gaby wasn’t quite sure that she did understand — weren’t

Christians supposed to forgive? — but she nodded anyway.

They met Christopher in the National Trust car park, with a view of the sea and the cliffs, as they’d arranged. Because it was so early in the season there were very few people, only a scattering of cars. There was a footpath leading down the cliff to the beach and the air seemed very thin and light.

‘This was my mother’s favourite place,’ Caz said.

Christopher was there before them, and was already out of his car, staring out towards the island of Lundy, apparently lost in thought. He seemed surprised to see Gaby; Caz couldn’t have told him she’d be there and Gaby thought that was unkind. But Christopher covered his shock well.

‘What do you both fancy?’ he said. ‘A walk over the headland? Then a pub supper?’ He was dressed like a country gent in a checked shirt and round-necked jersey.

‘Sure. Cool,’ Caz said. Gaby thought she seemed cool too. To the point of iciness. Gaby still wasn’t sure why Caz had wanted her there. As a witness to their reconciliation? To keep matters civil? Whatever the reason, she felt that, somehow, she was being used.

The cloud and fog had lifted and spring had returned again. The low sun turned everything warm and gold. Caz started talking as soon as they took the path onto the point. There was the honey smell of gorse.

‘I have such wonderful memories of my mum here. She was well then, easy, relaxed. We came to the beach together while you were working, Dad.’ Caz turned to Gaby. ‘Dad was in full business mode then, doing his deals, developing his plans.’ Christopher walked on in silence and Caz continued. ‘I loved exploring the rock pools, and do you remember when she bought me a little surfboard? I was so excited.’

‘I do remember.’

‘Do you, Dad? I wasn’t sure you took much notice of what we were doing those days. You seemed to have other things on your mind.’

Again, Gaby wondered why Caz was being so cruel, and why she’d felt the need for an audience. ‘Perhaps I should go back,’ she said. ‘Leave you two to it.’

‘No!’ Now Caz was being the bossy big sister again. ‘Please, Gaby, I need you here for this.’ They walked on for a while in silence. ‘I have this picture of my mother,’ Caz went on. ‘I was in the sea on the beach down there and Mum was watching. She had bare feet and her trousers were rolled up to her knees, a loose white shirt and brown arms, and sunglasses hiding most of her face. She was laughing.’

Gaby looked at Christopher, waiting for him to respond, but his face was impassive, almost quizzical, as if he wasn’t quite sure what was going on either. She felt so uncomfortable that it almost made her feel faint. There was something dizzying about the sound of the water way below them and the wheeling gulls. When Christopher did speak to Caz at last, it was about Simon Walden.

‘Have the police spoken to you again? Do you know if they’re any closer to finding the killer?’

‘I saw the red-haired woman, Sergeant Rafferty, at St Cuthbert’s,’ Caz said. ‘She was asking if any of our clients had come into money. She didn’t explain why.’

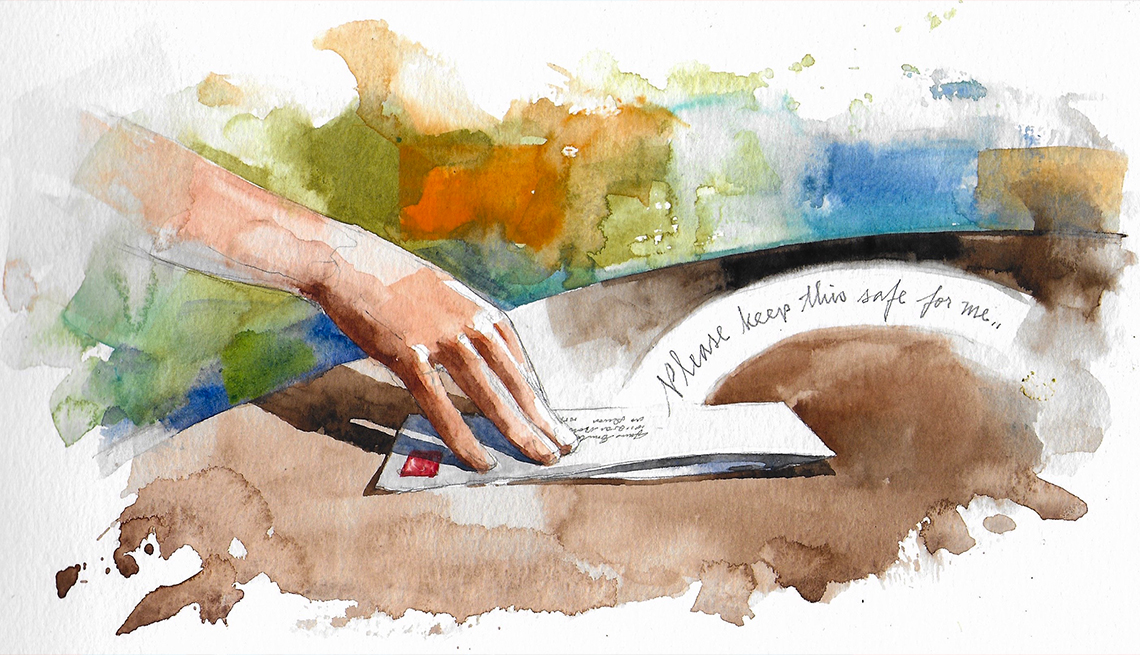

Gaby wondered if Caz would mention the key she’d found in Simon’s washing but she said nothing about that. In fact, Caz didn’t have the chance to say anything else at all, because Christopher Preece stopped suddenly and turned towards his daughter, blocking her way along the path.

‘You do know that everything I do is for you. That you matter more to me than anything in the world.’ A pause. ‘I’d do anything for you.’

Gaby watched with a mixture of fascination and extreme embarrassment. What was going on here? That sounded almost like a confession.

Christopher moved away from the footpath and sat on the grass. Gaby, who had never seen Preece as anything other than immaculately turned out, thought he’d get stains on his trousers. He turned to his daughter.

‘I did love your mother. You do know that.’

‘I know that you loved her at first,’ Caz said. ‘Before she was ill. Before it got hard.’

Another silence, broken by the sound of waves and the long call of gulls.

‘Did you love her at the end then?’ Christopher turned towards Caz and it sounded like genuine interest, not any kind of accusation. ‘When she was so angry, and unpredictable?’

‘She was my mother! Of course I loved her!’ The words came out as a cry at the same pitch as the gulls’ screech.

‘Really? Is that true? Did you love Becca when she turned up at your school? What did she tell your teachers? That she needed to take you with her because it was the end of the world and you both needed to be here at the beach to be safe from the disaster? It didn’t seem as if you loved her when I turned up to take her home. You looked horrified. Because she looked truly crazy, didn’t she? With that wild hair and the velvet dress that she always wore when she was going through a crisis, weeping in the corner of the headmaster’s office?’

Caz didn’t answer. Neither of them was taking any notice of Gaby now. It was as if she wasn’t there.

‘I did try to help her, to understand what she was going through,’ Christopher said at last. ‘But you’re right, it was too hard in the end. I escaped into my work. I told myself I needed to earn enough money to look after you both, to provide care for your mother.’

‘And with other women?’ Caz shouted at him. ‘Was that how you escaped too?’

He looked as if he’d been slapped, but still he kept his voice even, so quiet that Gaby struggled to hear it above the sound of the gulls and the waves.

‘What about you, Caroline? Didn’t you have your own means of escape? At first it was the pony club and then it was the church. You always liked your form of entertainment to be organized. A hierarchy. A ritual so you didn’t have to think too hard for yourself.’

Caroline seemed on the verge of tears, but Gaby couldn’t bring herself to intervene. She felt a horrible fascination watching the encounter unfold.

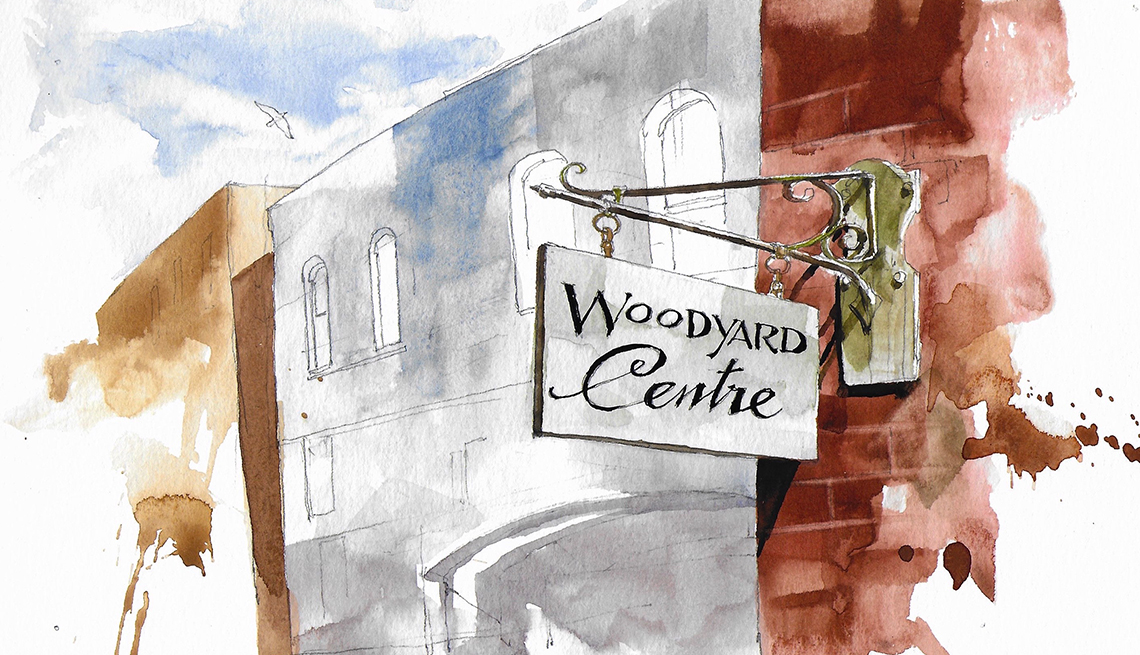

‘I’m sorry,’ Christopher said. ‘That was unfair. You were young and of course you wanted some structure in your life. There wasn’t much at home and it wasn’t your responsibility to look after Becca. That was down to me.’ He paused. ‘She would have been proud of what we’ve both achieved at St Cuthbert’s, wouldn’t she? And she’d have adored the Woodyard. All the terrific work that goes on there. The music and the theatre. The art. Don’t you remember how she used to dance?’

‘Yes, yes, she would.’ Caz turned to face him. ‘Is that why you got so involved in it?’

‘Of course. You must have realized that.’

‘We’ve never discussed it,’ Caz said. ‘I’ve tried to talk to you.’

‘I suppose that’s true. But I was always busy. A levels and then university.’

‘I wondered why you came back to North Devon after university,’ he said. ‘You could have lived anywhere. It must have such dreadful memories for you.’

‘Happy ones too, and this is where I remembered Mum best. Besides, I missed it when I was away from home.’ Caz seemed suddenly to make up her mind about something. She turned to her father. She was still standing and looked down at him, accusing.

‘Did you kill her?’

Gaby thought that was why she was here. As some kind of witness, in case Christopher was forced to admit to a ten-year-old crime.

‘No! Of course not!’ There was shock and immediate denial. ‘Is that what you’ve been thinking? All these years?’

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members