AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Nineteen

AFTER THE EVENING’S BRIEFING in Barnstaple, Matthew was discouraged. He felt the old insecurity biting at his heels, telling him he was useless, an impostor in the role of Senior Investigating Officer in this case. Perhaps Oldham would have made a better fist at it. They had so much information now that he should have formed some idea about who might have killed Walden, some notion at least of a strong motive, but there was nothing substantial, nothing to act on. Too many stray leads that needed to be followed up. And Christine Shapland was still missing. There’d be another night of anguish for her mother. Another night of Matthew knowing he’d let his mother down. On the way out of the police station, Jen Rafferty stopped him. ‘I don’t suppose you fancy a drink?’ A pause. ‘A chat. I could do with running some ideas about Walden past you. Today in Bristol, it was as if they were talking about a different man from the homeless guy who turned up pissed at the church. But I didn’t want to discuss it in there.’ She nodded back at the building. ‘It’s all too complicated and I find it impossible to think straight with an audience.’

‘Okay.’

‘Would you mind coming back to my house? I’ve hardly seen the kids since all this started. I probably won’t see them tonight. By this time, they’ll be holed up in their rooms. But at least I’ll know I’m there. I’ve got wine.’ Noticing his hesitation, she grinned. ‘Decaf coffee, herbal tea …’

He looked at his watch. It was already nearly ten and he’d been looking forward to being home, to being with Jonathan. But he trusted Jen’s instincts and was still weighed down by the sense of duty, drummed into him in childhood. ‘Sure. Just half an hour, though. I need my beauty sleep.’

He sat in Jen’s cottage. She’d lit the wood burner before running upstairs to check on her children and putting on the kettle, and the small room was already warm. She’d lit candles and switched off the big light. The edges of the space drifted into shadow. He felt himself grow drowsy and was almost asleep when she came in with a tray, mugs, a packet of biscuits. Her Scouse voice shook him awake.

‘Only digestives. The bloody kids ate the chocolate ones.’

He stretched, tried to focus. ‘What’s been troubling you?’

‘It’s Walden. When we first ID’d him, I had him pegged as a rough sleeper, a drunk, who’d been scooped up by a well-meaning do-gooder and helped to put his life back together. But I don’t think he was ever like that. I mean, I think he was a drinker and there must have been a moment of crisis when he turned up at the church and met Caroline, but he must still have had money somewhere. He can’t have drunk away two hundred thousand pounds. That’s a fortune! Besides, while he was working at the Kingsley he still had an income.’

‘He could have been a gambler. Reckless.’

She shook her head. ‘Nobody’s mentioned that. His business started falling apart because it expanded too quickly, but everyone put that down to Kate’s ambition, not because Walden was spending wildly. His wife or his mate would have told me if he’d had a gambling problem.’

‘What are you saying, exactly?’

‘That I’m not convinced he was homeless when he landed up at the church. He might have been lonely and depressed, but at the end of the season in North Devon, it’s not that hard to find a landlord prepared to let you stay in a holiday rental. Besides, that tiny room in Hope Street was almost empty when he was staying in it. He must have accumulated more stuff than that. I left home with two suitcases and a bin bag when I ran away from Robbie at an hour’s notice. I know I had two kids, but everyone has more possessions than a couple of pairs of jeans.’ She paused. ‘Gaby Henry had the impression that Walden was still fond of his wife, but we didn’t find a photo of her, or of his army mates in his room. I just don’t see it. And there’s a gap in the timeline between him leaving work at the Kingsley and moving into Hope Street. According to the women, he’d been rough sleeping during that time, but I spoke to the homeless guy who hangs out at the end of the street and he only came across Walden once he’d moved into number twenty. There’s a community of rough sleepers in Ilfracombe. They look out for each other. He would have come across Walden if the man had been living on the streets.’

‘You think Walden had a house or a flat somewhere and that his stuff might still be there?’

‘I think it’s possible.’

‘Nobody has come forward to say he’d rented from them.’

Matthew set his mug back on the tray and took another biscuit. ‘But would they recognize him? After all this time? Especially if he went through a letting agency.’

Silence. Jen opened the door of the wood burner and threw on another log. Matthew was thinking. Walden was a man who’d been described by Gaby Henry as being born to cook. If he had the money, he’d want a kitchen of his own. He’d have had his own knives, and they weren’t in the Hope Street house. The women had said that he often disappeared, that he spent time on his own.

‘Why would Walden pretend to be homeless? And why would he accept that depressing room in Hope Street if he had somewhere better to live?’

‘I don’t know,’ Jen said. ‘I’ve been thinking about that all the way back from Bristol. Do you think he needed the company? Female company? I mean in an inappropriate way — like looking through bathroom keyhole weird. Gaby described him as a bit of a creep.’

‘And if we’re talking inappropriate, what was he doing chatting up Lucy Braddick? Where was he going on those trips to Lovacott? Do you think he had a place there?’ Matthew was still obsessing about Christine Shapland and made a strange illogical leap. If Walden had his own accommodation away from Hope Street, perhaps the missing woman was being kept there. But that wouldn’t work, would it? Because Walden had been killed before she disappeared, so he couldn’t be responsible for her abduction. He was clutching at straws.

‘Get Ross on all the letting agencies tomorrow,’ he said. ‘And the estate agents, in case he bought a place. Let’s see if we can trace what happened to that money.’

It was raining again when he drove home. Braunton was empty, but there was a light in the toll keeper’s cottage. Matthew wondered what the Marstons could be doing in there and thought he’d be glad when they found somewhere more to their liking and moved away. They were his nearest neighbours and, driving past, he realized he disliked them with an intensity that surprised him.

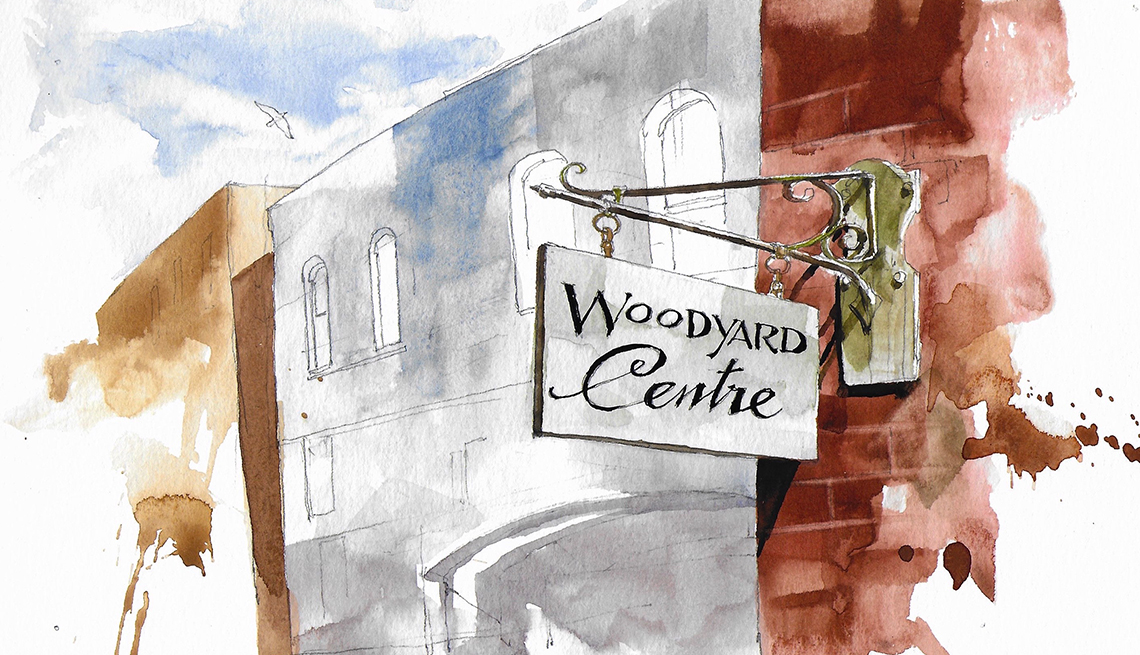

Jonathan hadn’t closed the curtains and must have seen the headlights of his car as he drove towards the house, because he came outside to greet him. He stood just outside the door, turning his face to the light rain. ‘Is there any news?’ He was talking about Christine Shapland of course. Jonathan had never been this involved in any previous case. He’d listened in the past while Matthew had run through his anxieties about an investigation, offered the occasional piece of advice, but this was different. This was personal. He knew the woman and besides, the reputation of the Woodyard, his life’s work, was at stake. Before Matthew could answer, he continued talking. ‘I’m sorry. Come inside. I shouldn’t have ambushed you like this.’ Jonathan put his arm around Matthew’s shoulder and drew him in, then clung onto him. It was as if Jonathan were drowning and needed support.

Chapter Twenty

EARLY NEXT MORNING, THEY were in the police station, fuelling up on caffeine, buzzing because there were so many things to do. Too many leads and possibilities, but this was better than the torture of waiting for something new to turn up.

Jen had slept deeply and felt well. If she’d been on her own the night before, she’d have opened a bottle of wine, called up to Ella to see if she fancied a glass, so she wasn’t drinking alone, then finished most of it herself anyway. But Matthew had been there, asking for camomile tea, so the wine had been left unopened. He’d listened to her, trusted her instinct about Walden, and that was where they started this morning.

‘We know now that Walden had access to a substantial sum of money. I need you to track it down. Now. I can’t understand why that hasn’t already happened. So, let’s have one person dedicated to that. Go through our fraud experts; they have contacts in the banks. It’s hard these days to open an account in a bogus name so it shouldn’t be difficult to trace. I think it’s highly possible that Walden was living in a flat or house of his own before moving into Hope Street. If we find his bank account, that’ll give us an address for him.’ Matthew was standing at the front of the room, softly spoken but demanding their attention. Jen knew a little of his background and thought there was still something of the zealot about him. She’d known nuns with the same passion, the same presence. She’d have followed them to the end of the world, believed every word they said. Until she’d grown up.

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members