AARP Hearing Center

Chapter Nine

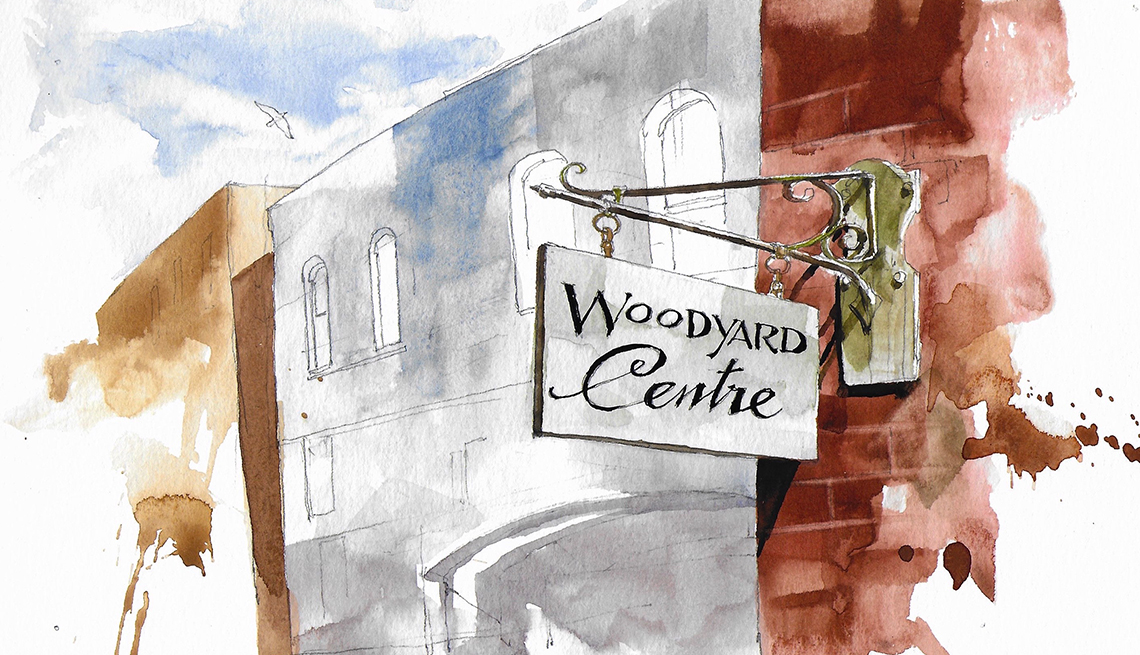

The Woodyard was a monument to Jonathan’s confidence and competence and Matthew regarded it with a mixture of pride and envy. He was a good detective, but he’d never achieved anything quite as great as this. This place would still be a derelict timber yard with a decaying warehouse at its heart if it weren’t for his husband. After his travels, Jonathan had returned home to Exmoor, taken a low-paid job as carer of a man with learning disabilities and loved it. He had the right mix of humour and compassion and worked his way through the system, without really meaning to, no end goal in sight, until he was managing a day centre. He’d loved that too and that was when Matthew had met him.

Matthew had been policing in Bristol then, the big city, only two hours from where he’d grown up but a world away: culturally diverse, buzzing, alive. He’d felt as alien there as he had in Barnstaple, but anonymous. Nobody cared that his family were religious bigots who’d disowned him because he could no longer believe in their God, or that he’d dropped out of university, because the academic pressure had stressed him almost to madness. He was good at his job and that was all that counted. He’d met Jonathan at a conference about working with vulnerable adults. There’d been a three-line whip from management that someone should attend and nobody else in Matthew’s team had been interested. It had been his fortieth birthday and Jonathan had been his present.

They’d kept in touch, spent weekends together, mostly in Barnstaple, quietly, under the radar. Not a real couple, Matthew had told himself. He couldn’t be that lucky. This was a phase that would pass. Jonathan would set off on his travels again or find someone more interesting. Instead, he’d found a new project. The Woodyard. It had been a time of local authority cuts and the day centre where he’d worked had been under threat. Jonathan had been transformed from a laid-back guy, who moaned about the restraints of his work but left it behind at the end of the day, to an activist, passionate, consumed, organized. Matthew would arrive from Bristol to Jonathan’s tiny flat in the oldest part of the town, tired at the end of a busy week, to find it full of people. Earnest people talking money, funding applications and lobbying, and arty people like Gaby from Hope Street, painting posters and planning social media campaigns. Businessmen in suits and radical activists all in the same place. Matthew had been intimidated and retreated into work. He’d been certain that Jonathan would find someone more interesting to spend his life with.

Matthew had been thrown by the change in Jonathan, the fact that he could be so serious. Until then he’d been the serious one, the worrier. Jonathan had drunk beer and sat in the sun. He’d always slept at night. In those days of planning and activism, every waking hour had been spent thinking about the Woodyard project. And he’d made it happen. Here it was, just as the planning committee had hoped. A glorious community hub bringing people together. Jonathan was general manager of the place. It was overseen by a board of trustees, but he was the man on the ground. With his assistant, Lorraine, he ran the centre.

Matthew had feared that once the Woodyard was up and running, Jonathan would become bored and restless again. That he’d run away. So, Matthew had kept his distance. No point getting too close. No point setting himself up to be hurt. Then, one Sunday afternoon in early autumn, Jonathan had taken him to meet his parents. The first time and Jonathan had been nervous, jittery. Not at all his usual self. They’d sat around a kitchen table scattered with farm accounts, wary dogs at their feet. Matthew had been reminded of the visits he’d made with his father to the customers who had never been able to pay on time. There’d been the same shabbiness, a sense in the air that was almost desperation. This couple, Matthew could tell, might live in a beautiful place, but they were poor. Like the dogs, the family had been wary. He’d had no real idea of what Jonathan’s parents made of him.

On the way back to Barnstaple, where Matthew would pack his bag before returning to Bristol, Jonathan had pulled into a layby near a little stone bridge. It was at the edge of the moor where the landscape became gentler. They’d got out and stared into the water. The trees on either side were changing colour and were reflected in the stream.

‘What did you make of them?’ Matthew hadn’t known what to say.

‘They’re not my parents. Not really.’ This wasn’t the confident Jonathan. The hand on the stone parapet was shaking. ‘I’m adopted. They didn’t tell me, though. I found out by chance when I was sixteen.’

‘That’s why you left home?’

Jonathan had paused for a moment. ‘Among other things. I got angry. A bit wild. Got thrown out of school.’ He’d been looking out at the hills, but turned back to Matthew. ‘Will you marry me?’

It had been the last thing Matthew had been expecting and it had taken him a while to realize this wasn’t a joke. Even then it had occurred to him that Jonathan wanted a father as much as a husband — although there wasn’t so much difference in their ages — but he hadn’t cared. He’d have agreed whatever the terms.

‘Yes!’ He’d shouted it so loud that they’d have heard it back at the farm, so loud that they were both shocked by the sound. He was, by nature, a quiet man. ‘Of course I will.’

The next day he’d asked for a transfer to the Devon force. Miraculously there was a vacancy and they were desperate for someone to start quickly. The following weekend, they’d gone to look at the house by the estuary, and they’d bought it, despite the danger of flooding. Matthew, so cautious and risk-averse, had decided it was time to be reckless.

Now they were in the Woodyard garden, eating lunch. It was odd to be here in his own right. Matthew had been to the Woodyard before, with Jonathan, to see plays and to attend exhibition openings. But only occasionally and only after he’d moved to Barnstaple permanently. They still weren’t much recognized as a couple in the town. Their worlds were very different. At first it had been an ordeal, presenting himself in public as Jonathan’s partner, smiling and shaking hands. After all, what did he know about art or theatre? Sometimes the anxiety that he would say the wrong thing or express an opinion that was foolish swallowed him up, made him want to run away or lock himself in the lavatory. Now he was here as Inspector Matthew Venn, investigating a murder, and he had to take centre stage.

They’d bought coffee and sandwiches in the cafe and were sitting on one of the benches outside the building. There was a view of the river and the tide coming in, that distinctive smell of salt, mud and decay. A group of older volunteers was tidying, sweeping up debris that had gathered on the grass over the winter, but nobody was near enough to overhear.

Matthew spoke first. They were close enough to hold hands, but he was here as a police officer and not as a husband and his words sounded oddly formal. ‘You think Lucy Braddick is a reliable witness?’

‘Absolutely. I’ve known her for ages. Since when the old day centre was still going.’

‘Jen’s just phoned with confirmation that Walden worked in the kitchen here. That must be where Lucy first saw him.’ Matthew paused. ‘How well do you know Christopher Preece? I didn’t like to ask in front of Maurice.’

‘He’s on the Woodyard board and without a donation from him, we probably wouldn’t have got match funding to renovate the place. You must have heard me talk about him and you’ve met him a few times. He was there at the beginning, at those first meetings in the flat.’ Jonathan paused. ‘He was behind the mental health project at St Cuthbert’s too. There’s something of the passion of the convert about him. The ruthless businessman who suddenly found a social conscience. Sometimes he can come across a bit arrogant. As if he has all the answers.’ ‘I met Christopher’s daughter, Caroline, this morning. She seems pretty driven too. She shares a house with one of your workers. Gaby Henry?’

‘Gaby’s amazing. We appointed her as artist in residence, but she’s brought the whole place to life. Her work’s stunning. One day it’ll put this place on the map.’

‘You, this, it’s all too close.’ Matthew felt the words come out as a cry. ‘You do see now that I’ll have to declare an interest?’ ‘Of course you should. But don’t withdraw from the case just yet. You’re better at your work than anyone I know and your investigation might lead you in an altogether different direction. Surely the answer is more likely to lie in St Cuthbert’s than here?’ Matthew could understand the sense in that, but he thought this case was complicated, twisted, the threads unlikely to be quickly untied.

Gaby Henry had arranged to meet him in one of the meeting rooms. She’d been running an art appreciation class and had obviously been showing a series of images on a screen. The group reminded him of the friends Jonathan sometimes brought home — they had intelligent, earnest faces. The women wore loose floral dresses, the men jeans and sweaters. Informal but at the same time a uniform. Matthew watched through the glass door as Gaby wrapped up the meeting. ‘That was fabulous,’ she said. ‘Thanks so much for your attention.’ She stood at the door as they drifted out and waited until they were out of earshot before speaking to Matthew.

‘Thank God that’s over for the week,’ she said. ‘I’ve never met such a boring, pretentious bunch!’

He couldn’t help smiling. He often thought the same about Jonathan’s arty friends.

Gaby led him back into the room. ‘Do you know what happened to Simon yet?’

‘Not yet.’ Matthew paused for a moment. ‘We have discovered that for the last week or so he’d been taking a bus to Lovacott every afternoon. Did he have friends there?’

Gaby shook her head. ‘I don’t think he had friends anywhere. I realized he’d been home late a few times, but often we were back late too, so we didn’t notice. We just assumed he was in.’ She seemed to be thinking. ‘We didn’t see him much, poor bastard. Only Friday nights when he cooked for us both. Other evenings he disappeared into his room. Caz might know if he had pals in Lovacott. She sometimes gave him a lift into Barnstaple.’

‘He never had any visitors?’

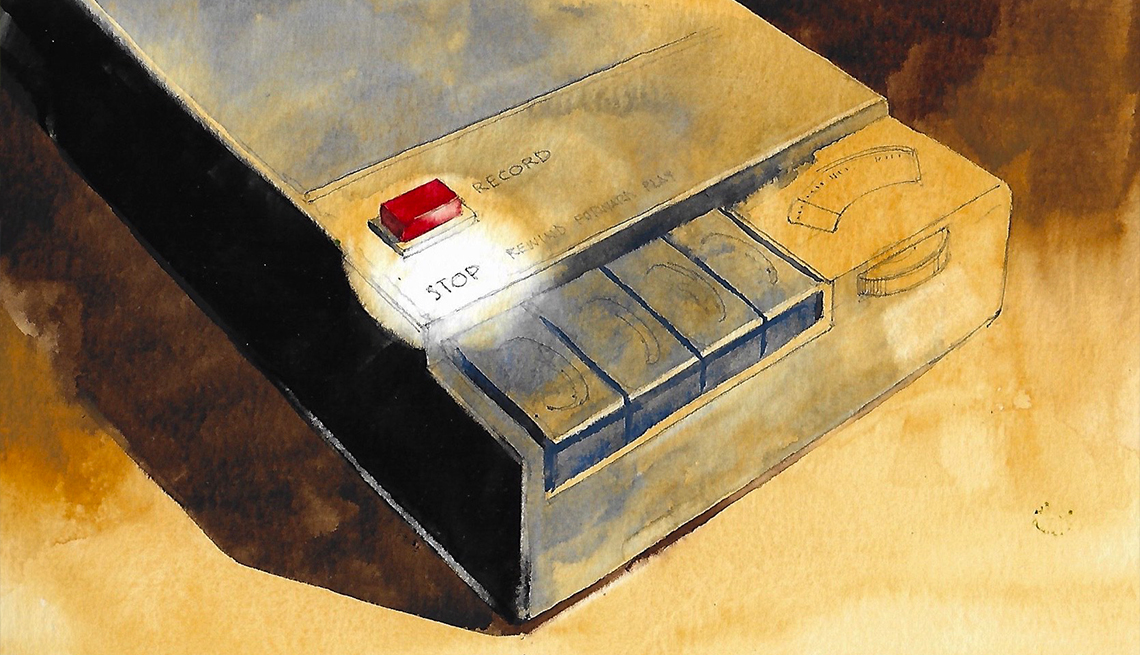

‘I never saw anyone.’ She paused. ‘Someone phoned for him once. We’ve got a landline but we hardly ever use it. We’ve got our mobiles. One day, I decided to check the landline messages and one had been left for Simon.’

‘Can you remember any details? The name of the caller? A number?’

‘Nothing like that. It was as if the guy on the other end of the phone assumed Simon would know who he was. Hi, Si! How’s this as a blast from the past. But I tracked you down in the end. I told you I would. You can’t escape your old buddies after all.’ She turned sharply, so she was facing him. ‘It sounds a bit sinister now, doesn’t it? But the tone wasn’t like that. It was friendly. As if they were old mates.’

‘When was the call made?’

‘I picked it up a couple of weeks ago. It could have been made a few days before that, though. Like I told you, we don’t use the landline much.’

‘Did you save the message?’ Matthew thought they needed to trace the caller whether he was a friend or an enemy. They knew so little about Walden’s past.

‘Of course! Because I told Simon it was there so he could hear it. He might have deleted it afterwards, though.’

‘Were you there while he listened to it?’

‘No!’ Gaby was firm. ‘None of my business.’

There was a moment of silence. Matthew texted Ross to get a trace on the phone and to pass a message to Jen to listen to the call. She might still be on the coast. He’d asked her to go to the hotel where Walden had worked once she’d finished with Caroline and he’d send her back to the house. Gaby had given them a spare key the night before. He felt a bubble of excitement rising in his stomach. The phone call might be an important factor in the investigation. This was why he loved the work.

‘Where were you yesterday afternoon?’

‘I was out on the coast,’ she said. ‘Making sketches for a painting I was doing.’

‘Where exactly on the coast?’

There was another moment of silence. ‘Not far from where his body was found. I wasn’t there to kill him, though. He bugged me, but it wasn’t as if he planned to stay in Hope Street indefinitely. According to Caz, he was starting back at the hotel once the season had started. He’d be living in.’ She stared at Matthew. ‘Come with me!’ Her voice was insistent and demanding. ‘I can prove what I was doing on the shore.’ She stood up. Without comment, he followed her.

She led him up two flights of stone steps to the top of the building without speaking. Refurbishment had ended at the lower floors and the steps were bare and uneven. When she threw open the door to a large room, he saw stained floorboards, crumbling plaster and old brick. It was flooded with light through sash windows on two sides. There was a filter coffee machine on a window ledge with a few dirty mugs, an easel, a pile of canvases leaning against one wall. Otherwise the space was empty, echoing. She nodded to the coffee machine. ‘Do you want one? I made it this morning, though, and it’ll be stewed by now.’

‘I’m caffeined out, thanks.’

She seemed a different woman in this space. The flip, easygoing Gaby of Hope Street was gone. She showed him the painting on the easel. A seascape, with a shimmering promontory of land. Crow Point, not where they’d found Walden, but seen from the other side of the marsh. There were bare patches of canvas.

‘It wasn’t going well,’ she said, ‘so I went back to do some sketches. I didn’t go through the toll road. I parked by the marsh and walked from there.’ She got out her sketchbook and held it out for him to see. Rapid pencil drawings that captured the movement of waves, the wingbeat of gulls. He recognized the shape of Crow Point in the distance.

‘These are very good.’ The words came out without thought. ‘That’s why I’m at the Woodyard. Because it gives me the time and the space to paint. The work is mostly mind-numbingly dull, like the class you just saw. A bunch of bored middle-aged and middle-class people, who think they have talent or that they understand art.’

‘Why did you accept the residency if you feel like that?’ ‘Because it pays.’ She spoke as if the answer was obvious.

‘I don’t have a rich daddy like Caz — my mother brought me up on her own — and I don’t make any money from my painting yet, so I do this. It’s better than stacking supermarket shelves or pulling pints. Just.’

He nodded back at the sketches. ‘Of course, this doesn’t prove anything. You could have done them anytime.’

‘But I didn’t.’ Her frustration was obvious.

‘Why did you dislike Simon Walden so much?’

‘I didn’t dislike him.’ She turned away. ‘I just didn’t see the point of him. If you don’t mind stepping over the needles in the morning or being harassed by the neighbourhood drunk, Hope Street is a pretty cool place to be. It’s the best house I’ve ever lived in. And I don’t mind those things. I didn’t need a man to protect me.’

‘Did Caroline?’ Matthew was surprised. He’d had them both down as strong, independent women.

‘Nah, but that was one of the excuses she gave for letting him stay. That we’d be safer with a man in the house. Which was pretty daft. We could have been letting in a maniac.’

More From AARP

Free Books Online for Your Reading Pleasure

Gripping mysteries and other novels by popular authors available in their entirety for AARP members